Believe it or not, there are still some secrets within the world of professional wrestling that are guarded with religious reverence. For outsiders looking in, it is difficult to understand the passion and vigilance towards upholding the veil of illusion behind lucha libre masks.

In the new documentary film, Lucha Libre: Life Behind The Mask, the filmmakers have attempted to tell the story of those who don the wrestling mask in the colorful genre of Mexican professional wrestling and the shield of secrecy that enshrouds it.

“I’ve always had an interest in wrestling, back from when I was kid — Chief Jay Strongbow, Gorilla Monsoon, George “The Animal” Steele — I have fond memories of that,” said Bill Hunt, an executive producer of the film and vice president of development and business affairs for Kralyevich Productions Inc (KPI-TV). “I tend to read about developments in wrestling and something that has always fascinated me was the whole industry down in Mexico.”

The one particular personality that has captured Hunt’s attention to lucha libre, it is El Santo and the culture that has spawned from his legacy.

Enrique Medina. All photos courtesy KPI-TV

“It took on almost mythic proportions to me — the movies, the comic books and everything else. I thought it would be interesting for us to delve further into it. There are so many layers to it than American wrestling.”

With his commitment to exploring this unique and rich realm of entertainment, Hunt and company would set off on a three-year film-making odyssey, starting in January 2003 that would evolve into a project that is much more than just another wrestling documentary.

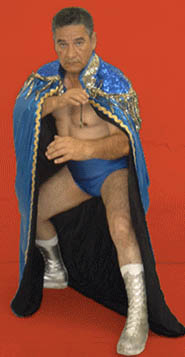

Rich Walton

Assuming the role of director for the project was Los Angeles-based Rich Walton, whose background includes stints as a field producer for both Reuters Television and CNN.

In selecting Walton, Hunt emphasized that his choice for director was made based on the need for someone who could blend both passion and focus to the subject matter over an extended filming period.

“I’ve known Rich for many years and I know of his talent and passion for sports in general,” explained Hunt. “I knew this would be the type of project that would require someone who would be able to stick with it for a long period of time. It wasn’t the type of thing where you could just call up the WWE offices and say ‘Okay, we’re going to go follow this guy, this guy and this guy.’ This is a type of thing where Rich had to become accepted into that culture.”

“We wanted a fresh set of eyes,” added Hunt, explaining how having someone like Walton, who had no intimate knowledge of the lucha libre culture, could present an unbiased view. “We wanted someone who didn’t know the culture. We didn’t want someone who was a big aficionado to do this. Everything he is experiencing is new and so that he’s experiencing it as I am or the majority of people on the street. You’re going to see it through the eyes of someone who wasn’t familiar with it.”

The culture that Hunt refers to is the East Los Angeles based lucha libre scene, ground zero for Walton to begin telling the story. As Walton explained, it would be no easy task to penetrate the curtain of protection surrounding this unique professional wrestling community.

“There’s really two aspects: there’s the cultural and language aspect of lucha libre, but there’s also breaking into the wrestling fraternity itself,” said Walton.

“I don’t think we really thought it was going to be that hard to walk in and meet these guys and then allow us to film them. There was that trust that had to get through first, that we were going to treat this subject with respect and not come in and just butcher it.”

“One of the keys for Rich in gaining their trust was that we weren’t there to make fun of them. We were there to hear their story,” added Hunt, crediting Walton in his ability to convey the sincerest of intentions. “I think after a time they realized that. It’s the way Rich was able to get backstage, the way he was able to see the wrestlers without their masks. Not all of them, of course, but the ones he became close to and trusted him.”

Having endured the initial false starts, Walton would eventually persevere and gain the trust of one of the key stars of the film, Enrique Medina.

“When we met Enrique Medina, he trusted us almost immediately, he was very friendly,” Walton said. “More importantly, he had the trust of the local wrestling community and in Mexico as well. We’re with him, therefore, we’re Okay. We got to the gyms and the guys would walk in to workout, without their masks, and would look at me, a guy with a camera, who obviously didn’t look like I belonged there. A little conversation with Mr. Medina and everything was fine. They trusted him because he trusted us.”

With his foot in the door, Walton would step forth and discover a variety of personalities as colorful as the masked luchadors. They included Medina, a 55-year-old barbershop owner who has wrestled since 1971. He also acts as both a referee and promoter.

Then there are the masked stars of the film, Kayam and Principe Unlimited.

Kayam, 44, has been wrestling for 25 years and comes from a family of luchadors. He is married with three daughters and when he is not wrestling, is a teacher.

Principe Unlimited

Principe Unlimited is 28 years old, the lone member of his family who chose to become a luchador and made his wrestling debut in 1997. Married with one daughter, he dreams of one day wrestling in Japan. When he’s not wrestling or working, he pursues his other passion as a church volunteer.

Others who are introduced in the movie include Medina’s devoted wife Benita and Albert, a 13-year-old luchador in training.

Bearing in mind how guarded luchadors are of their true identities, extra vigilance was exercised when in came to blurring the identities of those wrestlers who appeared in the film without their masks on.

“It was a pain in butt,” reflected Hunt on the technical challenge of censoring the footage. “We were very sensitive to it. We did let the wrestlers look at the film when it was completed to make sure we didn’t miss anyone. If they said ‘You really need to blur that person or that person’ then we’re going to blur them. That’s the trust they put into us.”

It was not lost on Walton in recognizing the special position he was in, to be granted the kind of exclusive access to the true identities of the luchadors he worked with.

“I found it to be a real privilege to be allowed back stage and film the guys,” said Walton, who told of the first time he saw Principe Unlimited without his mask at a pre-filming meeting at Medina’s barber shop. “He pulled up in his car (without his mask) and I was like ‘Wow, I’m actually going to see this guy’s face.’ I had been talking to him with his mask on this whole time, so there was some excitement. I really got into lucha libre and became a fan from working on this.”

But in one particular case, the veil of secrecy still remained entrenched for Walton as Hunt told.

“One of the wrestlers we followed was Kayam — he wrestles with his brother. We spent a great deal of time with Kayam and obviously shot him without his mask when we filmed it. During that whole period of time, you never saw Kayam’s brother without his mask. It’s not that his brother didn’t like Rich, but that’s how serious they take it.”

Protecting wrestling identities also came into play when Walton would follow the wrestlers to their homes and work, mingling with family, friends and co-workers, who had no knowledge of their masked personas.

“We had to be respectful in those times as well, because there were times that they were with people who did not know what they did on the side. So we had to make-up stories,” said Walton.

Kayam

An additional and more obvious challenge that Walton met head on was language. The majority of the film is in Spanish and Walton had to rely on his co-director, Carlos Garcia, to assist with both translation and other cultural aspects. Walton emphasized that participants were free to converse in the language of their choice.

“The guys did speak English, but we wanted to film them in whatever language they’re comfortable speaking in,” said Walton.

“There are a few spots where a couple of them do speak English. It just felt truer to us to have it in Spanish because this is from that culture,” added Hunt, noting that the film is sub-titled for English viewers.

When Walton submitted the final product for editing, he achieved what Hunt was looking for when it came to marketing the film to an audience made up of both wrestling and non-wrestling fans.

“You want a film to appeal to as many people as possible,” explained Hunt. “The intimacy was what we felt would draw in the lucha libre lover, the one who knows rudo (villain) and technico (hero). But what they don’t have is the backstage, to see the secret lives of these men, their alter-egos. For everyone to want to watch it, it had to be story driven. Obviously we have matches and there’s some great ring action. It wouldn’t be a lucha film if it didn’t have that.”

Having compiled all the footage he needed, it was time to edit the material in New York with Hunt and Kristy Sabat, vice-president of production.

“Looking at raw tape is always hard,” recalled Sabat upon examining the initial material. In time though, she began to see what Walton was privileged enough to view first hand.

“I knew right away that Rich had gotten into a world, that we had the right characters and the right stories. People’s eyes were going to be opened to something that was so special. The big thing for me was the cultural aspect of it,” said Sabat. “I come from a Hispanic family and didn’t really know much about this. I was less interested in the wrestling at first, then grew to become interested in the wrestling because I was so interested in these guys.”

Their combined efforts finally came to fruition this past summer when the editing was completed July. From there, the film debuted at HBO’s New York International Latino Film Festival.

It was at that particular event that some of the stars from the movie appeared in person.

“We owed them so much for bringing us into this world that they deserved to be at this moment that had taken us three years,” said Hunt.

“To have the guys see it finally on the big screen with the sound finally mixed — it looked great, it sounded great and we had a great screening,” added Walton.

Negotiations are now under way to have the film shown on a television network in the United States. Fans should also watch for the movie to play at future film festivals.

For Walton, not only can he take pride in having penetrated life behind the lucha libre mask, but also in gaining some new friends among those who star in his film.

“I definitely feel I was accepted to the point where I consider these guys friends now. I do go visit Mr. Medina in his shop from time to time, just to check in on him.”