On Saturday, October 21 Impact Wrestling held its Bound for Glory (BFG) pay-per-view.

If you haven’t seen it, it’s worth going out of your way to watch. The BFG card featured several exciting contests, including bangers between “Speedball” Mike Bailey and Will Ospreay, Chris Sabin vs. KENTA, and a main event between Impact World Champion Alex Shelley and former champ Josh Alexander. Traci Brooks and the announcing duo of Mike Tenay and the late Don West were inducted into Impact’s Hall of Fame.

Arguably the biggest news came at the end of the show, when Impact Wrestling President Scott D’Amore announced that as of the Hard to Kill pay-per-view on January 13, 2024, Impact will be returning to its original branding as Total Non-Stop Action (TNA) Wrestling.

Full disclosure: Despite D’Amore’s near-apoplectic enthusiasm (seriously, the promo he cut at the end of BFG alone is a screaming, swearing, sweating triumph of pro wrestling passion) I don’t see the big deal. Plenty of promotions have rebranded over the years, voluntarily and not so voluntarily.

Wrestling company names often change to reflect new ownership or broadened ambitions. In response to the then-WWF’s expansion plans, Bill Watts renamed his Mid-South Wrestling promotion the Universal Wrestling Federation because the universe is bigger than the world. Dallas territory owner Fritz Von Erich grew out of Big Time Wrestling into World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW) and later classed things up as World Class Wrestling Association, although the promotion’s broadcasts continued to use the WCCW name. In 1989 WCCW would be sold to Continental Wrestling Association (CWA) owner Jerry Jarrett. The CWA, or more broadly Memphis Wrestling has been through its own litany of owners and name changes, but the combined WCCW-CWA promotion would become known as the United States Wrestling Association (USWA). The merger wouldn’t last, but by the time it ended the Dallas territory was effectively dead. Owner Kevin von Erich would later enter into agreement with the Savoldi family, who ran the independent International Championship Wrestling promotion in the New England area, to use the WCCW name, creating International World Class Championship Wrestling (IWCCW) which lasted until 1995 and leaned on WCCW’s lineage, if not it’s talent. The USWA would continue in Memphis until its own demise in 1997.

WWE was founded in 1953 as the Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC). It was a member of the original National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). CWC rebranded in 1963 following a dispute with and exit from the NWA, becoming the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF). The WWWF rejoined the NWA in 1971. In 1979 it rebranded again, shortening its name to the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), which is where many of us got on this ride. The WWF would leave the NWA for good (for now, since nothing is forever in wrestling) in 1983, ahead of its national expansion.

In 2002, the WWF would be forced to rebrand following a dispute with the charity the World Wildlife Fund. The wrestling WWF had previously entered into an agreement with the environmentalists to limit its use of WWF outside the US, then failed to live up to the terms of that agreement. This dispute also gave rise to the all-time best bootleg wrestling T-shirt this side of “Dusty Sucks Eggs” or “I Broke Wahoo’s Leg” or “I Like to Hurt People”: the letters WWF accompanied by an image of a panda brandishing a steel chair. At least we didn’t get many “F*ck that panda” chants. More on that, later.

A fun, unlicensed WWF panda T-shirt.

Coming out of this lawsuit, the World Wrestling Federation became World Wrestling Entertainment. I have always thought was a dumb name, abandoning the pretense of being a quasi-sporting sanctioning body in favor of a producer of soap operas and making life harder for anyone who had to refer to the company. ‘The WWF’ makes sense grammatically — you’re the champion of THE federation. WWE has the same problem as World Championship Wrestling (WCW) or Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) — neither of those promotions were a ‘thing’, they were just descriptors and thus awkward to use in the simple shouted sentences that make up promos.

But I digress.

In 2011 yet another, perhaps stealthier, rebranding took place. Following Kentucky Fried Chicken’s transition to KFC which eliminated the reference to Fried, World Wrestling Entertainment removed wrestling from its name and branded itself exclusively as WWE. That’s right, the biggest wrestling promotion in the world is now a set of hollow initials, just like Ted DiBiase’s WxO or Mississauga’s UWA (at least they ‘borrowed’ a cool phoenix logo from Hyabusa).

WCW and ECW’s various rebrandings are slightly more complicated since they reflect changes in ownership and scope.

World Championship Wrestling was originally the flagship television show for Georgia Championship Wrestling (GCW), as well as an Australian promotion owned by Jim Barnett. Following the WWF’s brief ownership of GCW and its programming, GCW was sold to North Carolina-based Jim Crockett Promotions (JCP).

From there, things got muddy. Casual fans like myself might think of the promotion as the NWA, since JCP had consolidated its power over that sanctioning body’s board. Insiders referred to it as WCW while still under JCP. By 1988 whatever you called it, it was hemorrhaging money until purchased by Ted Turner and his broadcasting company. Turner initially incorporated the promotion as the Universal Wrestling Corporation but decided to use WCW as the promotion’s name publicly going forward. WCW would still use NWA titles until a dispute in 1993, which saw WCW leave the NWA and employ its own championships. WCW still nominally exists today, under WWE’s umbrella. I wonder if it will ever see the light of day as a freestanding promotion again.

Shane Douglas and Paul Heyman (with Tod Gordon to the right) at an ECW event in1993. Photo by John Arezzi

It should surprise no one that ECW’s name changes engendered controversy. The promotion that would become ECW began in 1990 under the name Tri-State Wrestling Alliance, promoted by Joel Goodhart. Goodhart would sell his share of the company in 1992 to business partner Tod Gordon. Gordon would rename the promotion Eastern Championship Wrestling, to reflect greater, but still modest ambitions. For most of its life, Eastern Championship Wrestling was a true independent promotion — albeit a large one with the means to develop local cult acts and supplement them with bigger name, former WWF and WCW talent at the top of their cards. Still, in 1994 Jim Crockett sought out Gordon with a view to reactivating the NWA and its world championship. What happened next would make pro wrestling history: following behind the scenes squabbles between Gordon and Crockett, and NWA President Dennis Coraluzzo, Gordon (along with his booker at the time, Paul Heyman, who would buy the promotion himself in 1995) would have the new NWA World Heavyweight champion Shane Douglas throw his new prize on the ground and break their new affiliation with the NWA in favor of declaring the Eastern Championship Wrestling title a world championship in its own right, and announcing the promotion’s new name: Extreme Championship Wrestling. ECW has stood as a brand ever since, inspiring loyalty like it was it’s own character. While ECW was never financially successful, it was and is hugely influential on modern wrestling. Even a dreadful attempt at a WWE-sanctioned reboot couldn’t kill it. WWE bought ECW’s assets out of bankruptcy in 2003 and attempt a series of pay per views and a TV series before giving up in 2010.

For Impact/TNA’s unassailable core fan base, returning to ‘TNA’ is seen as a positive step. Some fans have gone so far as to demand the return of TNA’s six-sided ring, which D’Amore and I agree would be a terrible idea. That ring was widely regarded as unsafe, and cropping off the traditional square’s corners left performers with a workspace that was so small as to look silly. Considering how much room is needed to carry off a modern wrestling match, truncating the ring for the sake of looking different was just not smart. Go watch any six-sided tag team match and wait for the hot tag spots. Then tell me when I’m telling lies.

Shannon Spruill in TNA. Photo by George Tahinos, http://gtsportsphotography.smugmug.com

In interviews after BFG, a marginally more subdued D’Amore claimed that he is responding to popular demand. D’Amore stated “we still hear the T-N-A chants wherever we go… Fans have longed for TNA Wrestling, so that’s what we’re bringing back in 2024.” SlamWrestling’s own Bob Kapur participated in a press conference with D’Amore following the announcement, with the key message that reverting to TNA branding should be seen as looking forward. For D’Amore, the name change reflects his hard work since his own return to the company in a management capacity in 2018, bringing “stability, consistency and respectability” to a promotion which had seen its share of controversy and the occasional existential threat. As D’Amore puts it “While we found that stability under the Impact Wrestling banner, we’re (now) ready to have our growth and our true success – our second golden era – under our true name: TNA Wrestling.” Addressing the challenges posed by potential associations with previous regimes, D’Amore reframed the question to focus on “celebrating what we do. Which is put on one of the best wrestling shows in the world. There’s no more apologizing.”

Wrestling media outlets have reported that the decision goes a bit deeper. For one thing, the name change restores some continuity to a promotion which has gone through multiple identity changes. It also promotes consistency. It seems as though some international partners never quite made the shift to Impact and preferred the older branding. TNA/Impact owner Anthem Sports and Entertainment (Anthem) had also allegedly polled fans, who expressed their preference for the classic branding.

Impact’s previous rebranding attempts have not been without controversy: names aside, when Anthem first took over, it also floated a new logo incorporating a cartoon owl, representing the new parent company. If wrestling fans weren’t impressed at first, Reby Hardy (whose husband, Matt was in the middle of an acrimonious split from Impact, which claimed it owned Matt’s successful ‘Broken’ persona) went viral with a social media rant that ended with “and f*ck that owl” shirts were made, fans chanted, D’Amore brokered a deal that saw Hardy ride off into the sunset, intellectual property intact, and the owl was quietly removed.

Jerry Jarrett, Christine Jarrett and Jeff Jarrett. Photo by Jim Cornette

Whatever name TNA/Impact chooses, at this point the key thing is to stick with it. Founded by Jeff and Jerry Jarrett in 2002 after WWE had largely monopolized professional wrestling in the US, the company was originally titled NWA: Total Nonstop Action (NWA-TNA). The Jarretts promoted the company via its association with the faltering National Wrestling Alliance, although TNA was not an official member. It would drop NWA from the masthead in 2004, leaving us with Total Nonstop Action Wrestling, abbreviated to TNA even though the S and W should have been in there as well. TNA would use the NWA’s World Heavyweight and Tag Team championships until 2007, when the agreement between NWA and TNA expired.

TNA became Impact in 2017, following Anthem’s purchase of a majority stake in the company. Eric Bischoff has suggested that this change came at the behest of TNA/Impact’s then-network home, Spike TV. Bischoff has said that Spike TV actually paid for the re-branding, since the TNA name was seen as juvenile, inappropriate for a high-profile cable outlet with a prime timeslot and a need to appeal to mainstream advertisers.

Within a few months of Anthem’s attempted rebranding to Impact, the company announced a merger with founder Jeff Jarrett’s new pro wrestling venture, Global Force Wrestling (GFW). The timeline is dizzying. Anthem announced the merger on April 20, then announced that they would take on the GFW name in June. By October Anthem split with Jarrett and GFW, reverting back to the Impact brand.

Jarrett has commented on the return to TNA on his My World podcast with Conrad Thompson. He said that he was against the switch to Impact in the first place, and that he urged Anthem not to go through with it. In Jarrett’s view, Impact was “dead on arrival” and would lose a large portion of an established brand’s fan base. Jarrett echoed D’Amore’s concerns that international partners were not on board with the switch and felt that the double entendre aspect was not as prevalent overseas. Despite his removal from the company he founded, and the lack of an invitation to participate in Impact’s recent 20-year anniversary shows (in fairness, other talent contracted to other promotions like Samoa Joe or AJ Styles weren’t there either), Jarrett says he wishes TNA well and is excited to see D’Amore’s vision for the future.

TNA/Impact’s fortunes as a company are of greater interest than its name. The company was born of the ashes of WCW, long after WWE had raised the old territory system and cherry-picked the WCW acts it considered marketable and affordable. Former WCW Champion Jeff Jarrett was one of the WWE’s Undesirables. He had hopscotched between WCW and the then-WWF during the Monday Night Wars and was rumored to have burned WWF management after they allowed his contract to expire despite him holding the Intercontinental Championship. A deal was brokered that would see Jarrett to stay on long enough to drop that title to Chyna before rejoining WCW, but the financial terms were steep enough that Vince McMahon held a grudge.

Billy Corgan is handed the NWA World Heavyweight title by an injured Matt Cardona on June 11, 2022, at the Alwayz Ready PPV. Photo by Hiban Huerta/NWA

With WCW and ECW having been absorbed into WWE and the independent scene at a low ebb, TNA defaulted to the second largest professional wrestling promotion in the US. In terms of box office and artistic merit, TNA would frequently trade off with Ring of Honor until the latter was purchased by AEW after the COVID pandemic. The rise of All Elite Wrestling (AEW) and its broader network television presence combined with the optics of Impact/TNA promoting in smaller, half-empty venues suggest that whatever you call it, Anthem’s wrestling promotion has slipped to number three. Add in Billy Corgan’s recent announcement that his National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) has secured a network deal of its own, and D’Amore and co. may be in for a fight to keep that position. Worse, Corgan bought the rights to the NWA after a short and bitter tenure investing in TNA.

Pro wrestling is funny like that.

Going back to TNA and name value, I remember when TNA first started. I was happy to see a second potentially national promotion in the wake of WCW’s death but found there were plenty of barriers to taking TNA seriously. A weekly pay per view model might have seemed like a way to draw revenue out of the chute, but for an untested brand it was a definite bar to participation. Absurd and juvenile characters like the Flying Elvises (a trio of talented wrestlers who were wasted in a gimmick that Wayne ‘Honky Tonk Man’ Farris did infinitely better), Cheex (a superheavyweight in the mold of Haystacks Calhoun or the McGuire twins, without the in-ring skills) or the Johnson Brothers (a pair of walking phalluses who presaged Joey Ryan’s dick obsession) weren’t going to make me watch either. Neither was the unfettered car crash nature of the angles TNA shot, which lacked coherence and were quickly forgotten — sometimes within the same broadcast. The wrestling itself was often good and sometimes great, and best when TNA relied on a mix of underappreciated veterans and new, game-changing talent who had yet to be plucked by WWE. But they were often overshadowed by senior ex-WCW and WWE names who seemed to lack motivation — or by Jeff Jarrett himself, who like most promoters made himself the center of the action, likely out of a combination of ego and the need to play good defense at a time when WWE would steamroll any would-be competitors.

Vince Russo

I took the TNA name itself as a reason not to take the upstart promotion seriously. Legend has it that TNA was originally proposed by Jeff Jarrett’s then real-life friend and frequent collaborator, Vince Russo. Russo, freed from the standards and practices of network television, and the editorial oversight of Vince McMahon or whoever headed Time Warner, wanted to create a decidedly adult-oriented product. His original vision for TNA would have seen full nudity, as some have called it “porn wrestling.” Vestiges of this idea persisted in those early characters and angles, although without the actual adult content they just came across as gross. Russo’s version of TNA had its more common meaning, meant to spotlight the naked ladies. I can’t quite get away from the idea that bringing back TNA branding means we’re cheering for “tits and ass.”

I want to devote a whole other column to Russo, whom I still consider a mad genius. Many of his ideas failed, but he had an outstanding creative output and his approach to storytelling continues to reverberate through modern wrestling — even if he’s not such a fan. I’ve called out what I consider some of his mistakes here on occasion, but I still think he’s long suffered from pro wrestling’s revisionist approach to its history. In any case, while I spotlight his earlier, raunchier work, for fairness’ sake I should note that in October 2003 Russo experienced a spiritual awakening and like many in pro wrestling, became a Born Again Christian. He defends the stories he told during his time in wrestling, but he is vocal in his current podcasts that he would do things differently today. A person can be more than one thing.

As noted, I’m less fussed about a promotion’s name than I am about the product they sell. And whether you call it TNA or Impact over the years I’ve become a fan. In-ring, I’d say Impact’s action stands up to any promotion’s, big or small. Their storylines are often goofy, but their overall approach to wrestling within a much smaller budget than their biggest competitors lends itself to a fun, “let’s put on a show” vibe in contrast to the often self-serious presentations used by the likes of WWE, NJPW or AEW. I don’t know what kind of budget D’Amore has to work with, but between the roster, the small venues used to tape its TV shows and pay per views, and the relative lack of pyro and ballyhoo I’m guessing it’s not huge.

And that’s not a bad thing.

Jerry Jarrett and Dixie Carter. Photo by Bob Kapur

Throughout its various incarnations, it’s been clear that TNA has never drawn a profit on its own. Previous owners, notably Dixie Carter, spent large sums on money to make it look as though TNA could compete directly with the WWE. You can argue about the effects that more advanced production, overseas tours and big-name veteran signings had on the company. To an extent, they gave the promotion an air of respectability — but really, they took the brand away from its origins and depleted Carter’s pocketbook. D’Amore, who has promoted his own Border City Wrestling indy fed since 1993, has shown just how much more can be done with less. His shows are tightly written and engaging, with an emphasis on wrestling and a winking acknowledgement of the ridiculousness of pro wrestling plots. If you look over the roster, it’s almost a mirror image of Corgan’s NWA — a mix of young up and coming talent, big league veterans who never quite fit in in New York (or I guess, Jacksonville now), and independent scene stalwarts.

Broken Matt Hardy. Photo by Lee South

The roster is fluid, and wrestlers are free to work elsewhere when they’re not booked. D’Amore may have saved TNA when, following Matt Hardy’s exit, he set a policy that allowed TNA talent to take their gimmicks with them when not employed by the company. It’s an advantage for workers who bet on themselves, free from one of the biggest criticisms of how WWE treats its “independent contractors.” D’Amore freely acknowledges that he cannot compete on salary, but he has been open about working with talent to structure contracts to allow as much freedom as possible. It makes continuity a thing but has the benefit of leaving me wanting more when a favorite moves on. If Impact rebranding to TNA means an influx of resources from Anthem, I’m on board.

At one point I would have thought that Impact’s best way forward would be a merger with AEW. A couple of years ago, when talent and titles moved freely between the promotions, I was sure that AEW CEO Tony Khan was footing Impact’s bills, much like Vince McMahon kept ECW afloat since it wasn’t all that solvent either. Now I’m not so sure. Pro wrestling mergers only seem to work if they’re kept behind the scenes, and each promotion is allowed to cater to and build its particular audience. Khan’s run with ROH has shown that like JCP buying the UWF, or the merger between the CWA and WCCW to create the USWA, that is much easier said than done. If bringing back the TNA name helps forge that brand’s independence, who am I to speak against it?

Although I admit, the circularity in TNA’s naming suggests a merger might one day happen…

NWA-TNA II, anyone?

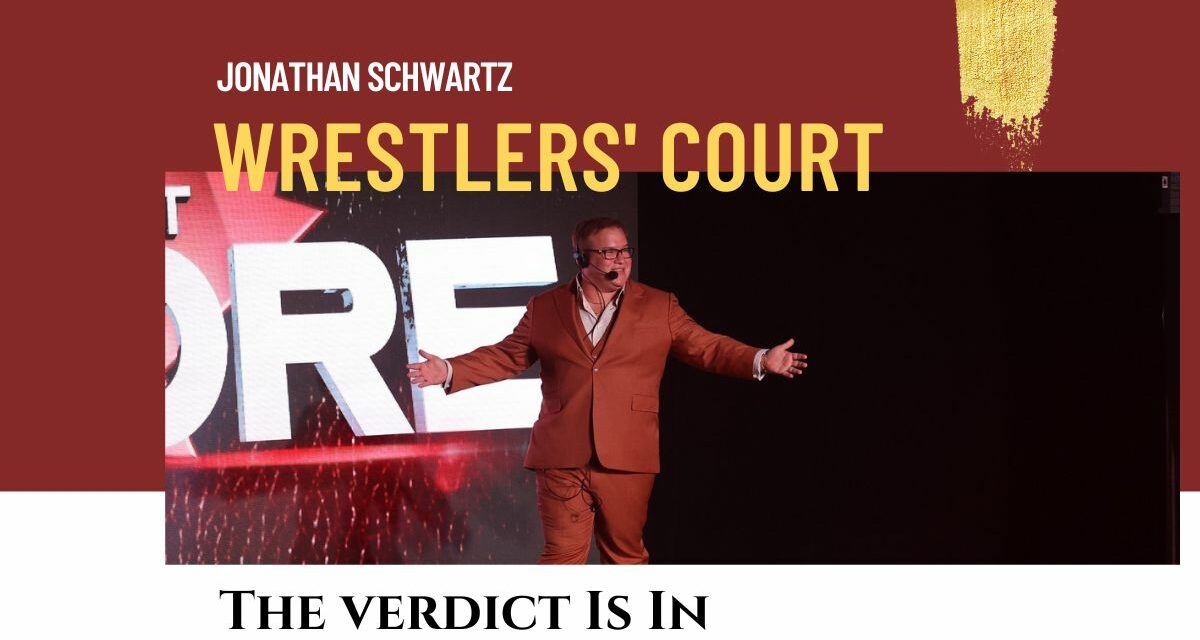

TOP PHOTO: Scott D’Amore at Impact 1000 on Saturday, September 9, 2023, at the Westchester County Center in White Plains, NY. Photo by George Tahinos, georgetahinos.smugmug.com

RELATED LINK