One of the great things about diving into old wrestling cards is that it allows me to explore different aspects of the topics I enjoy about classic wrestling.

My favorite topic of discussion is Jack Pfefer. Honestly, it’s not even close – just ask my friends, family, and coworkers. He was such a character in every aspect of his life – and especially when it comes to his creations. And that brings me to this card:

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Jack Pfefer’s promotional mind is his concept of soundalike knockoff names. Perhaps no Pfefer knockoff is as infamous as Bummy Rogers – a poor man’s Buddy Rogers, although countless others are dotted throughout his career, including Bruno SamNartino, Hobo Brazil, Ted Blassie, and the Swedish Angel.

So, you would think the “Slave Girl Zoolah” would be a shot at Lillian Ellison, the legendary “Fabulous/ Slave Girl Moolah,” right? Not so.

What people get wrong with Jack Pfefer is that they apply an archaic 1920s wrestling thought process to Pfefer – and understandably so. After all, he got his start in 1924 and was a heavy hitter in New York by the end of the decade. He maliciously aired his dirty laundry to the gleeful press in 1934, a hammer blow to the industry that many feel lasted until the introduction of television some 15 years later.

But Pfefer’s wrestling mindset was much closer to Vincent Kennedy McMahon’s than Billy Sandow, Paul Bowser, or Ray Fabiani. Those men placed a premium on not just the name – but what that name could bring to the table to entice and excite their customers. Pfefer, like McMahon, saw talent as interchangeable cogs, with the name the draw, not what that name was attached to.

The obvious parallel would be with the fake “Razor Ramon” and “Diesel” characters of 1996-97 WWF, but it’s faulty. McMahon’s knockoffs were designed to damage the credibility of Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, the original characters, while Zoolah here is simply just the name, nothing more, nothing less. In fact, Moolah was working with Pfefer at the time – and was working against the same Lady Angel across the northeast just six months before.

Moolah was a crucial player in Pfefer’s camp, helping him to compete with Billy Wolfe, a former ally and another leading promoter of women’s wrestling in North America. So Pfefer partitioning off a knockoff name to another talent is extra strange – but it’s something he had previous history with, as the first instance of “Bummy” Rogers was in California in 1946 – and even predates Buddy Rogers’ own arrival in the state (under the Pfefer umbrella) later that year.

The best I can come up with is to imagine Jim Crockett Promotions in the mid-’80s when there were two “Nature Boys” simultaneously. And not only were there two men with the nickname “Nature Boy,” but they both sported suits, sunglasses, bleach blonde hair, and held championship belts.

But what happened with the “Zoolah” character is still far odder. It would be as if Ric Flair and his World Championship vanished off Mid-Atlantic television and Buddy Landel and his National Championship were inserted into the storylines without explanation.

Well, the explanation was that this was the world-famous “Zoolah,” so clearly, this one was the real deal, and everyone (including your trusted local promoters) had just so happened to get it wrong before (and in the future). It’s odd business – but it’s how Jack Pfefer saw his talent (with notable exceptions).

Like McMahon, Pfefer saw himself as the unquestionable pinnacle of the business and sought to chisel (read: bilk) his talent of as many nickels and dimes as he could. After all, he was Jack Pfefer, the “man who saved wrestling” and a hero of the nation’s press. To him (and McMahon), wrestling was a show. While the stars were the grapplers, the real genius lay behind the scenes, with the theatrical impresario who pulled the strings and made his puppets dance.

“It was a system, he frankly admits, he borrowed from the circus and the sideshow,” and a system saved the wrestling business (according to Ted Carroll in the August 1969 edition of The Ring Wrestling magazine, a very friendly media ally of Pfefer). This was sports entertainment, old-school style.

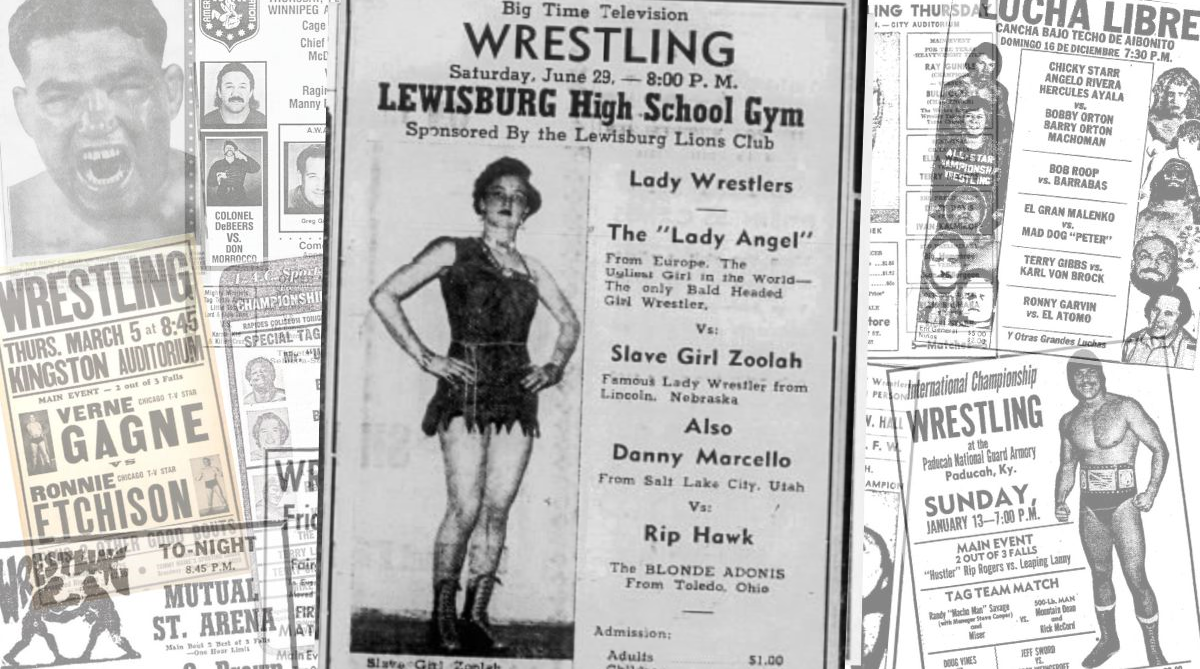

It’s a strange tactic (and one I wouldn’t recommend to any up-and-coming promoters). Still, it’s one Pfefer continually used – particularly for cards like today’s – a sold show for the Lewisburg Lions Club in Lewisburg, Kentucky. I would be stunned if the workers on this card made more than $150 combined.

Oh, here’s the card for tonight, by the way:

Lewisburg High School, Lewisburg, Kentucky * Saturday, June 29, 1956

- The Lady Angel vs. Slave Girl Zoolah

- Danny Marcello vs. Rip Hawk

Lewisburg is a small town outside Bowling Green, situated about halfway between Louisville and Nashville. The show was likely booked through Joe Marshall, the promoter in Bowling Green for several years in the 1950s.

Sold shows were a great way for local communities to raise money by staging matches at a local gym or VFW hall, with all proceeds going to the sponsoring group. It was also a great deal for the promoter – they would agree to a flat fee from the local group beforehand, then plan the card based on that budget.

I’m guessing the coffers of the Lions in Lewisburg weren’t overflowing when this event was staged on June 29, 1956. The card is a stubby two-match affair, with Zoolah taking on a rising star in the women’s ranks, the Lady Angel.

Lady Angel was one of the seemingly endless “Angels,” spawned from the very popular Maurice Tillet, the “French Angel,” a major star for Paul Bowser and Eddie Quinn throughout the 1940s. Pfefer’s “Angels” (which he says he created, of course) started with the “Swedish Angel,” a knockoff who rose to fame in his own right and went on to include “Angels” of all shapes and sizes, including the Canadian Angel (Jack Rush), the Colorado Angel, the Polish Angel, the Italian Angel, the Golden Angel, and our villain for today, the Lady Angel.

Lady Angel has all her own lore, thanks to her “deformity” – her bald head. Eventually played by at least three (maybe four) women, this “Angel” was Geneva “Tommy” Huckabee, who worked almost exclusively as a Pfefer talent for her entire career up to her untimely death in 1966.

According to the lore, the Lady Angel was a recent arrival from Europe (usually Germany), where the young Angel suffered a horrible youth. She lost her family (and her hair) in an Allied bombing raid, with the young girl the only survivor suffering from life-changing burns. Fortunately, escaping prisoners of war helped spirit her to safety in the West.

But her scars and her bald head were too much for society. Shunned and mocked by society, she turned to the only outlet she knew she could make money and get the respect she deserved: wrestling.

She was a figure of fascination to the press, with “the lines of horror and grief etched across her face.” To fans, she was a terror, constantly breaking the rules and showing aggression far beyond what was expected, not just of a wrestler but a female wrestler at that. Upon the disappearance of Lady Angel in 1962, one fan was quoted as saying.

“Someone got to her at last. How long can she go on wrecking other wrestlers like that? They got her with a knife or a gun.”

This is nonsense, but it shows just how successful the Lady Angel character was. It’s worth noting that the different versions of the Lady Angel were distinct, with unique origin stories for the character’s “grotesque” bald head.

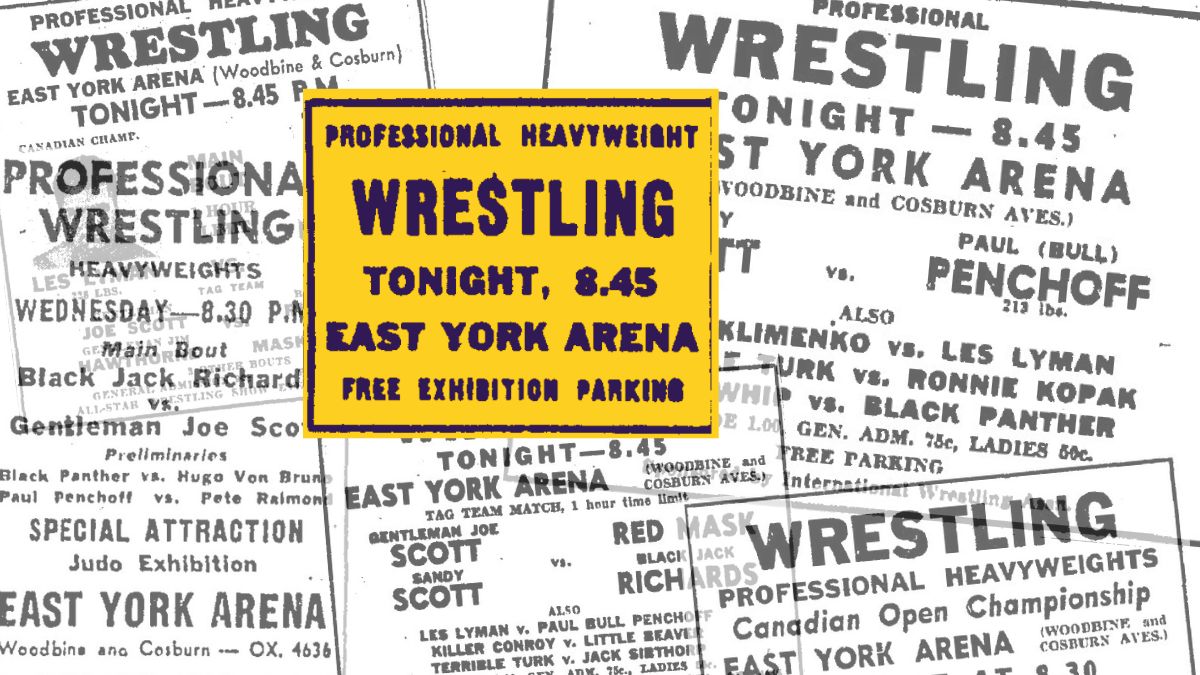

Yulie Brynner, perhaps the best-known Lady Angel, portrayed a Chicago-born widow who lost her hair and husband in a fiery crash with a gas truck. Both Huckabee and Brynner (sometimes Jean Elbon of New York or Jean Noble of Lincoln, Nebraska) would hide “her deformity” by wearing a wig and glasses, as seen below.

Brynner was so good at hiding that you probably didn’t even see her – but she’s there. You know, like in this article? Yep, that Lady Angel was this “Slave Girl Zoolah.”

Wrestlingdata.com (the grand arbiter in these matters) has this “Zoolah” as Kay Noble, but I’m not sold. For one, the Lincoln, Nebraska billing doesn’t fit Kay Noble, nor does the image look like Kay, but rather Jean Noble.

Are they one and the same, related, or none of the above? Honestly, I’m not sure, so feel free to chime in below or drop me a line on social media (@cory_m_santos) and let me know – I’m all ears.

This stub of a card also includes another big name at the very start of his wrestling journey: Rip Hawk. Born Harvey Evers (no relation to Lance), his upbringing was tough, set against the bleak backdrop of the Great Depression. Originally debuting in the professional ranks in the late 1940s, he would find his greatest success upon his return from the Korean War in 1954.

At this point, Hawk was a regular fixture in Toledo, making a name for himself across the Midwest and southern United States. According to Steve Johnson in his SlamWrestling obituary for Evers, he had turned pro around his 18th birthday for promoter Cliff Maupin, promoter of the Terminal Athletic Club in the city. Eventually, he landed in Chicago, wrestling and training for a year with Karl Pojello, the manager of the French Angel, at a camp of future all-stars such as Johnny Valentine, Don Marlin, and Man Mountain Dean Jr.

Hawk is most associated with Swede Hanson, who formed the very successful Blond Bombers tag team – multiple-time tag champions of territories as varied as Australia, Amarillo, Florida, and Jim Crockett Promotions. He later formed another successful partnership with his “nephew,” a young, still chunky Ric Flair.

Hawk’s opponent for the evening was Danny Marcello, a heavyweight from Salt Lake City, Utah, and the trainer of Len Denton, a man who knew a fair bit about grappling. Over a 20-year career, he wrestled under many monikers, including Joe Pizza, Eric Von Krupp, Joe Mercer, and the Mighty Prussian. Here, however, he is under his real name, as the “Fighting Mormon,” the Latter-Day Saints enjoying considerable wrestling success in the middle of the 20th century, thanks to stars like Marcello, Don Leo Jonathan, and Dean Detton.

While spot shows like this were cheap to run and often overlooked by coverage in major regional media, they provided an essential entertainment and sporting service to the smaller communities that dotted the territories (both NWA and otherwise) throughout the century. It’s these spot shows where countless fans first found their love of wrestling … and one I can recall fondly from my own first-time pro wrestling experience, at the Warwick Musical Theatre in Warwick, Rhode Island, in 1994.

And it gave me another chance to blab on about Jack Pfefer.

RELATED LINK