“Life’s hard; New Japan training is harder” – Bad Luck Fale

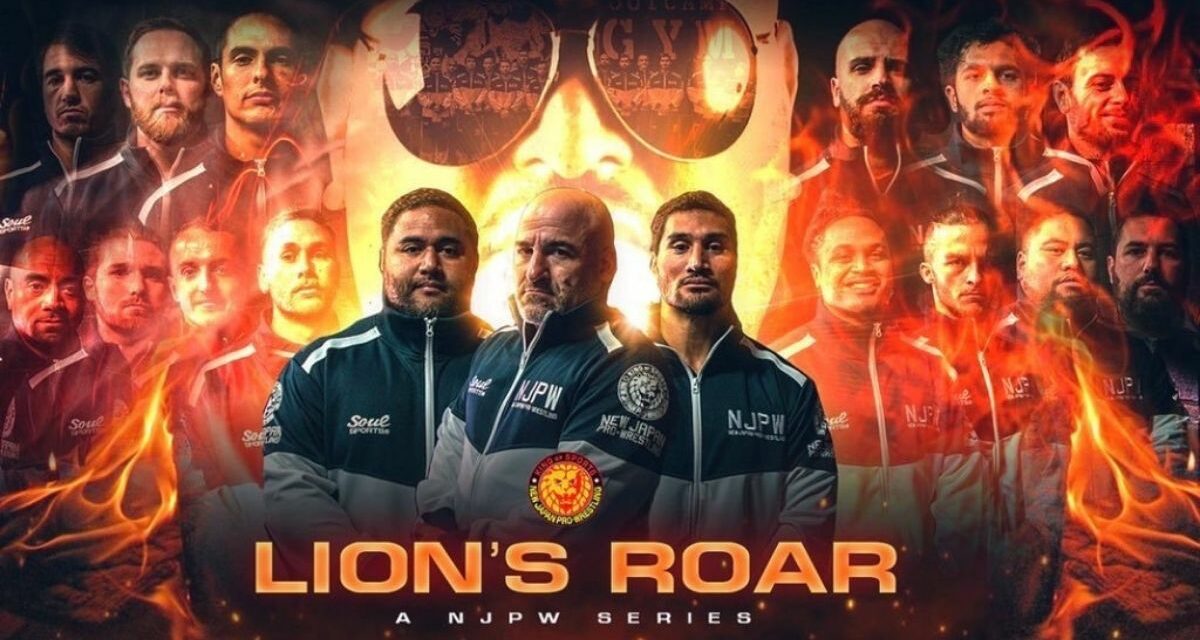

Over the decades, many wrestling fans have asked themselves, “How can I become a pro wrestler?” That question is answered through one of New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s newest series, Lion’s Roar. Available exclusively on NJPW’s streaming service New Japan World, Lion’s Roar offers an interesting glimpse into the lives of wrestling hopefuls.

The show is hosted by Toks/Bad Luck Fale (Simi Taitoko Fale, 40), who is introduced as the first foreigner to complete New Japan’s dojo training system. He went through the exact same rigorous training program as the native Japanese talent. And by completing the training (or, in Fale’s own words “surviving”) he earned enough respect to open his own satellite training facility in New Zealand.

The 11-part series, released weekly and now completed, gives fans a fantastic glimpse into the training done for New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW), the largest wrestling company in Japan and once the second-largest company in the world. New Japan, like most Japanese promotions, still holds to the notion that pro wrestling is more or less a sport since the industry never really had its own ‘pro-wrestling is fake’ moment that took off with the populace. As a result, Lion’s Roar is seen through that lens of legitimacy. This isn’t a reality show with scripted lines and manufactured drama. Instead, the focus is on 13 aspiring wrestlers striving to become NJPW stars and the grueling lengths to which they must go to achieve those dreams.

“You wouldn’t be able to name me any other sport that you have to be so physical one night and then the next night do the same thing over and over and over. Fighters and boxers fight three or four times a year, sometimes less. But we [wrestlers] have to do this every night for up to 250 times a year. And we still have to keep the same intensity, the same adrenaline rush. You have to figure out how to go to sleep, how to get up at certain times. Every day’s in a different city, sometimes a different country and the time zones are different. That’s why New Japan is so tough. The training teaches you how to be mentally tough.” – Bad Luck Fale on the nature of professional wrestling

Shot in Auckland, New Zealand, Lion’s Roar follows a standard training camp that shows just how intense and legitimate the training in Fale’s dojo is. Inspired directly by Fale’s own training in the company’s main dojo in Japan, Fale believes that the key to creating solid pro wrestlers is a combination of discipline, repetition, conditioning, and teamwork. This is seen throughout the series: the trainees must take care of themselves and each other outside the ring (really in Fale’s old house converted into a dormitory plus outside the ring in the dojo) as much as they do between the ropes. Fale’s philosophy brings the classic trope of ‘Japanese discipline’ to life: the trainees are taught how to greet and address each other in Japanese, they are told to keep the house and the dojo perfectly clean (Fale: if I walk into your house and see a dirty toilet, what does that say about you?) and their lives are regimented strictly. At the same time, the trainees are taught a sense of community, family, and collective responsibility. If one wrestler struggles, everyone suffers. If one trainee goofs off or can’t keep up with the training, everyone has to restart.

And yet, no one falls behind or becomes bitter or resentful towards the others; the trainees are taught to take care of each other and help each other so that they can succeed as a group. This is seen with one of the trainees, a heavyset man, who struggles to keep up with the conditioning training and regular exercises early on. When he falls over, they help him up and work with him instead of leaving him behind. And towards the end, he’s one of the first to move into the dojo to continue regular training and by the show’s end he’s one of Fale’s most promising trainees.

The Fale Dojo trainees carry an enormous tire around a huge Auckland block as punishment for failing to clean a stand in the dojo’s entranceway. Those that can’t touch the tire must piggyback on each other’s back and switch back-and-forth while their brothers carry the massive tire. Photo courtesy of New Japan Pro-Wrestling.

Of course, there’s reason to believe that he and all of the other trainees struggle at first: New Japan’s – and by extension, Fale’s – idea of punishment is to make trainees train harder. In one of the earlier episodes, as punishment for failing to keep the toilets clean, all the trainees must do 1,000 squats. And if one of them fails, they have to restart at zero. By the end of the session, the 13 trainees finished well over 2,000 squats as a group.

That just covers the tip of the iceberg in terms of training. On top of physical conditioning, hundreds of squats, push-ups, running up slippery and rocky hills and steep sand dunes and multiple other strength tests, there’s also intense grappling training. The notion of New Japan’s strong style being ‘legitimate’ and ‘a fight’ is drilled into the trainees’ heads from day one. They do plenty of amateur grappling and basic drills that could break anyone just as easily as the core endurance training. By Episode 9, around half of the trainees have suffered one injury or another. One of them – Mark Richards, a former Young Lion training to get more experience – suffers an Achilles strain. And he mentions that, throughout his training, anytime he grabbed his heel or showed any pain, his trainers would motion to the door and recommend that he leave. But he stayed on, determined to bounce back after being ripped apart by NJPW commentators for being so far beneath the LA Dojo trainees to whom he was being compared.

Naturally, some viewers might look at this series and think the process strange at best or barbaric at worst. But the truth is that this is part of the culture of pro wrestling. Wrestling and New Japan do exist in their own worlds to a degree, with their own rules and expectations. The one thing Fale looks for out of these trainees is heart, and the best way to show that is to persevere and keep going despite whatever setbacks one might suffer.

“You really have to give up everything. It’s not like a regular job. You’re going to have to do a lot of work for very little money. A lot of travel, a lot of expenses out of your own pocket… for very little money and very little thanks a lot of the time. – Tony Kozina, co-head wrestling coach, Fale Dojo

But not even the cloistered world of pro wrestling is immune to the realities of the wider world. Throughout the earlier episodes the specter of COVID lingers in the background but never really plays a part in the show. Then the Delta variant hits and it throws the final episodes (along with Fale’s larger plans) into disarray. Due to the restrictions, the wrestlers are given a choice: either stay in the house or risk breaking the rules and train with Fale and the other coaches. Four trainees follow Fale while the others stay behind. This leads to the closest thing to ‘reality TV drama’ to take place on the show. Two of the trainees contact the film crew directly and ask to be filmed without getting permission from Fale or anyone else. Not only does this violate the senpai/kouhai chain of command instilled at the very beginning, but it also puts the crew’s lives at risk. Needless to say, Fale and co-head coach Tony Kozina are not happy.

The series ends on a somewhat somber note as the pandemic situation in New Zealand worsens. Lockdowns and restrictions make it impossible for anyone to really train or work in the ring. The trainees only get one exhibition match to showcase their pro wrestling skills, which is far less than what they’d get under normal circumstances. And by the end, some of them are forced to leave as the dojo can’t operate at all. The final scene shows a group of remaining trainees grappling on the grass to practice as Fale advises on what would normally happen: he would send his assessments back to New Japan and they’d tell him who they want. Instead, no one learns whether or not they’ll move on. A few do leave and return home, others stay on in the house until restrictions lower, and others still remain in the dojo awaiting the chance to train some more.

“If you look at that mountain ahead in the distance you’re going to trip on the pebble in front of you” – Tony Kozina

The trainees assemble a wrestling ring that Fale built by himself. The canvas used in this ring is the same canvas from the finals of the 2016 G1 Climax that saw Kenny Omega win the tournament. Photo courtesy of New Japan Pro-Wrestling.

Lion’s Roar isn’t meant to be a cheesy TV drama or some kind of shock TV about the brutality of the sport of professional wrestling. Instead, it comes across as a mix between a documentary and a story of inspiration. At its core, Lion’s Roar highlights just how intense the training is to become a professional wrestler. These men undergo intense physical stress to train their bodies for a very difficult profession. And as time passes, the training does not get easier; their bodies simply become more adaptable to the pressure and intensity. They learn to work together and help each other to share in victory and share in defeat. Viewers see and hear what this wrestling training means to these rookies, from the sacrifices they’ve made to get there to the pain they’re in on a daily basis, to the struggles – physical and mental – they endure from both the training itself and the pandemic’s effect on it and them.

It has been said that hard times build hard men. If that’s so, then the trainees that endured Fale’s dojo must be made of iron at this point. And since every modern New Japan star has gone through this exact sort of training and then some, one can only wonder what those wrestlers are made of.

NJPW’s streaming service New Japan World is the only place to watch Lion’s Roar.