On February 10, 2022, All Elite Wrestling (AEW) Champion “Hangman” Adam Page sent out a Tweet. It read “im tired of bleeding every month [sic]”. The Tweet appeared following a brutal, weapons-filled Texas Death Match against Lance Archer, in which both men bled profusely. A few weeks earlier, Page bled in consecutive matches against challenger Bryan Danielson (Danielson opened himself up as well in the second match). Page didn’t even have to don his ring gear in order to bleed against then-champion Kenny Omega. He was busted open at the contract signing for the match where he would eventually win the title; Omega signed said contract in Page’s blood.

Blood seems to be a fixture in AEW across their cards. Former champions including Omega, Chris Jericho and Jon Moxley have all suffered for their art. Dustin and Cody Rhodes juiced heavily to support a grudge match that resolved a family feud. Emergent top heel Maxwell Jacob Friedman (MJF) bled heavily in a War Games style double cage match. AEW’s women’s roster has done the same: Dr. Britt Baker in a match against Thunder Rosa, and Taynara Conti in a relatively low-stakes grudge match. Taken together, these instances and more suggest that at the very least AEW is less concerned about its performers’ use of blood to add drama to their matches… or else sees blood as a way to differentiate AEW and tap into the more hardcore product that grown-up fans remember and miss.

MJF takes a bite out of Chris Jericho at AEW Blood & Guts in May 2021. Courtesy: AEW.

Blood (especially the kind drawn by a wrestler him or herself) has long had a place in wrestling. Used sparingly, it communicates the intensity of a fight or the brutality of a beat-down. World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) mostly put an end to bloodletting in the 1990s as it sought a younger audience. This policy has on occasion been honored in its breach, especially during the Attitude Era when storylines aged to suit a rabid teenage/college age fan base. Blood was arguably essential in the creation of at least two relatively recent, major stars. One of the enduring images of my own fandom is a bloodied Stone Cold Steve Austin passing out from Bret Hart’s Sharpshooter at WrestleMania 13, his face full of gore. More recently, Becky Lynch took the lead in redefining WWE’s approach to women’s wrestling as “The Man”, a similar anti-authority world-beating character. The toughness needed to underlie this character shift was cemented with an errant blow from Nia Jax during a pull-apart brawl. Jax exploded Becky’s nose. It is worth noting that the former happened without management’s approval and the latter was by accident. Both images are memorable in part because they’re so rare.

Less memorable was Dustin Rhodes’ and Barry “Blacktop Bully” Darsow’s double blade job in the back of a moving truck for World Championship Wrestling (WCW). Not only was this mostly forgotten, it barely registered due to some dodgy camera work and got both men fired.

Outside WWE blood has long been a way for promotions to brand themselves as extreme or outlaw. Historically, promotions across the US used blood to increase the excitement and in some cases cover for less than stellar workers, Men like The Sheik and Abdullah the Butcher built careers around walking to the ring, rolling their eyes, and drawing blood-their own and their opponents’ (both men also played mute characters-so much for promos).

Abdullah the Butcher against Mad Man Pondo. SlamWrestling.net file photo

Paul Heyman’s Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) filled buckets of blood-necessary to add realism to the parts of their show that involved hardcore, weapons filled matches. ECW folded but successor organizations like Combat Zone Wrestling (CZW) and Game Changer Wrestling (GCW) have followed suit; upping the level of violence… which is part of the problem. Where blood is used regularly, it ceases to be dramatic and becomes a crutch for performers who are not strong enough performers to connect with an audience without hurting themselves for real.

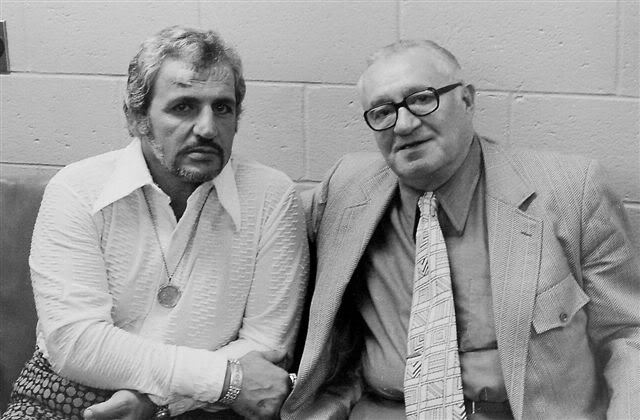

WWE’s policy against blading has a strong precedent. For decades one of the more successful territories operated out of St. Louis, Missouri under Sam Muchnick. Mr. Muchnick presented his matches as more straightforward athletic contests and generally sought to keep the action clean and in the ring. Legend has it he once brought The Sheik in for a run; after watching as The Sheik went through his typical match: throwing his opponent outside the ring, brawling, using weapons and bleeding, Muchnick cancelled the rest of The Sheik’s appearances and sent him on his way.

The Sheik and Sam Muchnick. Photo by Dave Drason Burzynski

Matches where both opponents bleed present increased risk for blood-borne illness. Abdullah the Butcher was successfully sued by Canadian wrestler Devon “Hannibal” Nicholson, who alleged that Abdullah gave him Hepatitis during a blood-soaked contest (ironically, Nicholson has since generated controversy for drawing blood in an unsafe manner from other opponents and non-wrestling personnel-most recently a referee in Texas). “Cowboy” Bob Orton saw a late-career WWE run as his son Randy’s manager end prematurely when he bladed without having disclosed that he was positive for Hepatitis as well. At this point, bleeding as part of a wrestling show careers known health risks for performers. COVID-19 may not be transmissible by blood, but the optics of bleeding while you have a masked audience don’t look great.

When a heroic underdog character like Page is bloodied, it can be an effective way to draw sympathy from an audience. Page is tapping into a familiar vein, arguably best used by the Rhodes’ brothers’ dad, Dusty. Using a similar babyface cowboy gimmick Dusty bladed as a matter of course in his feuds. His scarred forehead told a story of overcoming insurmountable odds and literally leaving a piece of himself in the ring. I question whether Page needs to do this at all. Rhodes was an immensely charismatic performer and one of the best talkers ever as he got older (and bigger) he could move well for his size but his matches were more about drama than performance. Page isn’t nearly as charismatic as Rhodes was, and his presentation is less about identifying with the underdog than his being relatively normal and self-questioning in the face of challenges (they’ve slowly weaned him off of a Stone Cold adjacent dependence on beer drinking). But Page is in great shape and can work long matches effectively against a variety of opponents. His overall game is strong enough that he doesn’t need the extra drama, especially when it may put his health at risk.

If you think about it, in 2022 bleeding in a professional wrestling match is anachronistic. Practiced by men like Dusty and Abdullah and The Sheik (and countless others whose foreheads are swollen and scarred), it helped reinforce the reality of wrestling… but kayfabe is not even an open secret anymore. We know it’s ‘just’ a show, even if the show is athletic and carries a degree of risk for its’ performers. This may be part of blood’s residual appeal-to the segment of the audience that watches hoping for legitimate, car-crash style injuries. I love wrestling and accept that blood has a place in limited spots. But as a fan I hate the idea that people are legitimately getting hurt-or worse-hurting themselves, for my entertainment. The beauty of pro wrestling is its ability to tell a physical story safely for all involved.

When it comes to blood, AEW can do a lot more with much less.

TOP PHOTO: It’s double blood as Adam Page is mauled by Lance Archer in Atlantic City, NJ, on February 9, 2022. Photo by George Tahinos, georgetahinos.smugmug.com

RELATED LINK