As the First World War dragged on, professional wrestling fizzled out across Canada. The prospect of holding events showcasing unarmed combat between some of the fittest and strongest men in the world, who had nevertheless decided against donning a uniform, fell into disfavor.

While wrestling cards, at least of a civilian nature, became few and far between, the skills of a professional grappler nevertheless proved to be useful when retooled for military purposes. This was particularly true when it came to generating publicity for recruiting, and no Canadian wrestler put those skills on better display than Toronto’s Artie Edmunds.

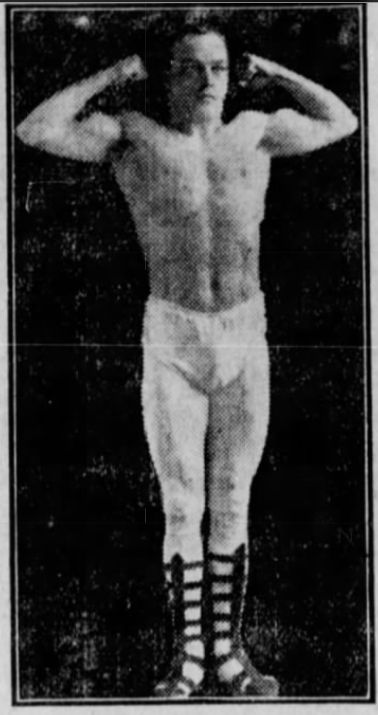

Artie Edmunds.

Artie Edmunds began his career as an amateur at the turn of the century. After considerable success, he transitioned to the paid ranks. Although only weighing 125 pounds at a height of 5 foot 4, he became one of Toronto’s best known mat stars, claiming the featherweight championship of America. Despite his diminutive stature, Edmunds was endowed with prodigious strength and an impressive physique, leading him to being dubbed “The Pocket Hercules.” Beyond his mythic moniker, he also invited frequent comparisons to contemporary bodybuilding standout Eugen Sandow, widely considered to be the world’s most perfectly developed man around the turn of the twentieth century.

Physical skill alone did not ensure success in the paid ranks of professional wrestling, even in an era when mat contests were gambling-driven enterprises that lacked many of the histrionics that later characterized the sport. Personality and showmanship still mattered. Edmunds enlisted the managerial services of Lou Marsh, well known Toronto athlete, sports journalist, and namesake of the Lou Marsh Award, given annually to Canada’s top athletes as determined by a panel of sports journalists. Marsh’s larger-than-life persona was frequently on display in his colorful sports columns for the Toronto Star, and his protégé quickly developed a willingness to engage with both the public and the press. Edmunds frequently regaled them with stories of his various mat encounters and forays into the boxing ring, and staged publicity stunts which included letting people strike him in the stomach with a five-pound hammer.

Artie Edmunds in action.

Although touted as a “Physical Marvel,” years of gruelling athletic encounters had taken their toll on Edmunds by the time Canada went to war in 1914. Some of his boxing matches were particularly brutal. His battle with Billy Lauder in Winnipeg on May 25, 1906, was described by the local Tribune as “The Worst Pounding Ever Handed Out to [a] Prize Fighter in the West,” and his right eye was badly damaged in a fight in New York in 1907. In 1910, his vision in both eyes was further impacted by an aggressive weight cut brought about by a contract stipulation that he make the ringside weight of 124 pounds for a wrestling match against fellow flyweight Ernie Sundberg. As a result, despite possessing a physique that, in the Tribune’s estimation, “Rival[ed] Sandow in Muscular Development,” he was repeatedly rejected for military service. As the war dragged on, however, demand for enlistment became intense, and Edmunds’ professional skillset proved useful for the Canadian military.

In the fall of 1915, the Canadian government enacted a policy that enabled individuals or communities, as opposed to local Militia regiments, to raise their own battalions, provided they covered the costs of recruiting. While the policy was justified on the grounds that the job of bringing men into service was too big a task for the Department of Militia and Defence to do alone, one of the consequences was intense competition among the fledgling battalions, all of which were seeking to get their ranks up to full strength. Star athletes, as military historian Tim Cook notes in At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1914-1916, were considered to be valuable additions to military units, and battalion records often specifically noted their addition to enlistment rolls. The ballyhoo and bluster possessed by professional wrestlers such as Artie Edmunds, however, were particularly valuable during a period of intense recruitment.

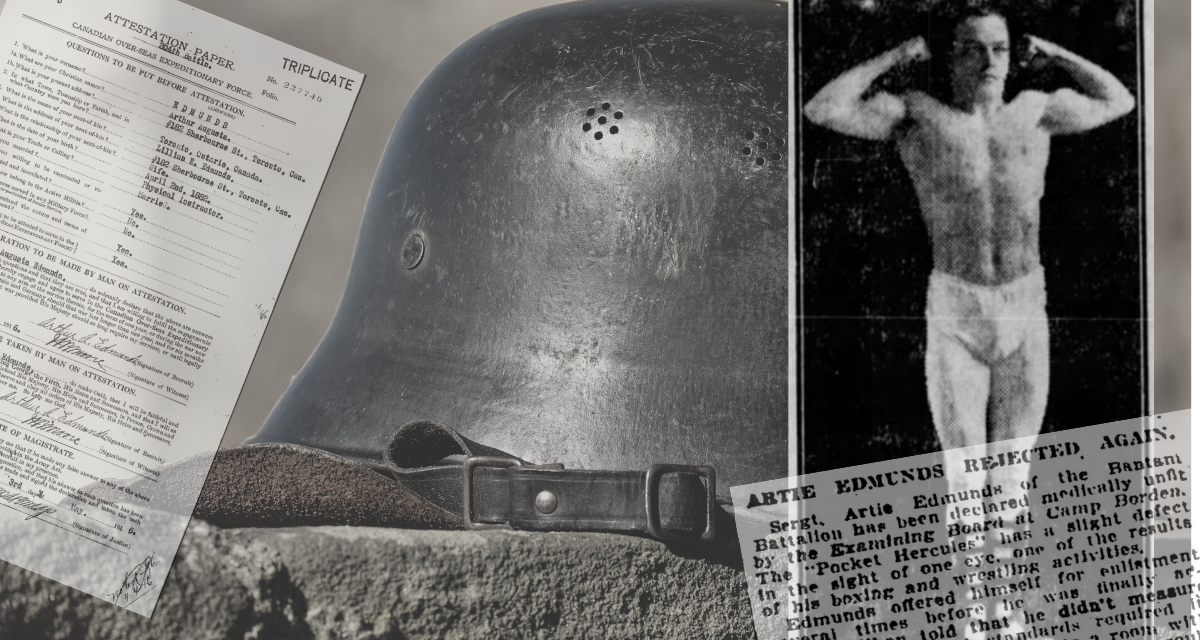

After his failed attempts to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), Captain Joseph Lawson of Toronto’s 204th Beavers Battalion, which began recruiting during early 1916, arranged for a special board of examiners to hear Edmunds’ case. Appearing before the board, Edmunds asserted:

You know, I have been around here a good many times bothering you by trying to recruit. Now, you go out and pick out four men from any battalion you want to, put me in a room, tell your four men that I’m a nuisance around here and that you want me beat up. If they beat me up I’ll stay away, but if I come out of the room and leave the four behind, then I want to be taken on.

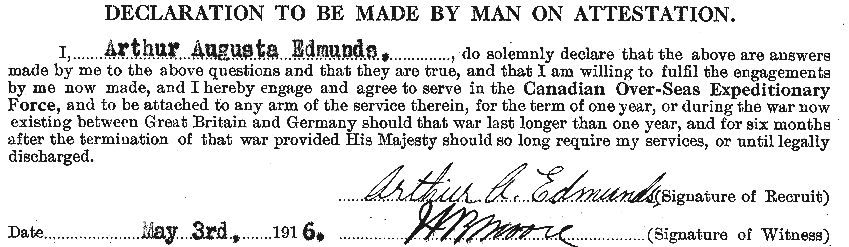

Edmunds’ plea, which bore many of the features of newspaper challenges from the period (not to mention present-day in ring promos), received widespread coverage in the Toronto press. He also won over the examination board, and was taken on by the Beavers on May 3, 1916. Medical records from the time of his enlistment noted his defective right eye but categorized it under “slight defects but not sufficient to cause rejection.”

His Attestation Paper, dated May 3, 1916, notes that Arthur Augusta Edmunds, living on Sherbourne St. in Toronto with his wife, Lillian, has a “L. ear slightly deformed.”

Now in uniform, Edmunds’ flair for self-promotion was harnessed by the 204th.

Three weeks after enlistment, Edmunds attended a local wrestling program headlined by grappler George Sparta. Sparta was offering to throw any soldier in the audience: at the time, a common promotional tactic used by professional wrestlers both in theatre performances and carnival-based athletic shows. The Telegram reported that, although “ordered by his doctor to quit wrestling for a time, he felt the itch of battle… [and] it grew too strong for him to resist.” Edmunds made a counter offer to Sparta to the effect that if he could not beat the much smaller “Pocket Hercules” in ten minutes, he should enlist with the 204th. Sparta stated that if he couldn’t accomplish the task, his whole troupe would enlist with the 204th. After first facing off against a smaller wrestler who was part of Sparta’s entourage and successfully lasting an agreed-upon period of five minutes, Edmunds went the distance with Sparta.

The publicity surrounding Edmunds’ enlistment and subsequent recruitment coup brought attention to the 204th. Undoubtedly, it also added to the general pressure being directed toward healthy men who had not yet opted to join the CEF.

Artie Edmunds’ military career did not last long. Suffering from head pain and insomnia which warranted hospitalization, an examining physician further noted in his medical records that, “This man has been blind in the right eye since 1908.” On August 9th, he was discharged on the basis of being medically unfit for service. The Toronto Globe reported that Edmunds was “very much disappointed by this turn of affairs.”

Edmunds’ case is illustrative of the value that star athletes, and in particular star wrestlers, held for the military during the First World War. Although involvement in their chosen vocation was, at least in Canada, curtailed for several years, their transferable job skills were a boon for the CEF during a time of aggressive inter-battalion competition for men. The Beavers, in particular, recognized the value of a star athlete with a flair for publicity like Edmunds. The January 30, 1917 edition of the Toronto Star identified the 204th as the city’s top-recruiting battalion among those raised in 1916. Their savvy promotional strategies, which included bringing the “Pocket Hercules” into uniform and letting him ply his trade, contributed significantly to their success.

As for Edmunds himself, he continued to be involved with sport, including as a boxing matchmaker, until a terrible accident.

On Saturday, February 25, 1922, Edmunds was crossing at the corner of Dundas and Keele in Toronto’s west end when, as the Globe reported, he “was run over by a street car, which was making the ‘Y’ at that point. Both legs were badly crushed.”

The incident was a major setback, but not the Achilles heel for the Pocket Hercules. Edmunds continued his work as a physical fitness instructor before meeting a tragic, and somewhat foreshadowed, end.

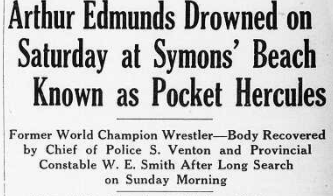

On August 17, 1935, while on a boating excursion off of Symons Beach at Bowmanville, Edmunds dove into the water a quarter mile off shore. He did not resurface. Dredging operations turned up his body the next morning. It was his final, though by no means first, shadowy encounter with water.

In 1907, he saved three people from drowning while visiting Blue Point on Long Island, New York. This was despite the fact that Edmunds was a non-swimmer. By 1910, Edmunds himself had been reported drowned at least two times. Longtime associate Lou Marsh, noted following Edmunds’ death, that just a few years earlier he had jumped into the frigid abyss of Lake Ontario as part of a publicity stunt staged in conjunction with a cold weather physical culture exhibition. Marsh recalled, “We had to pick him out with a rope and a little buoy… and he did it twice because the photographer missed the first shot.”

On his passing, Marsh also recounted that Edmunds was “game almost to madness” as a combatant and won many of his contests by “sheer courage and staying power.” Those same qualities, consistently borne out by observations made throughout his career, led a near-blind man to demand a role in “The War to End All Wars,” but also brought about his watery demise.

RELATED LINKS