The list of wrestling stars-turned-movie stars is almost too long to enumerate anymore. The Rock. John Cena. Dave Bautista. Crossover fame and fortune awaits almost any mat star who has the desire and skill to hit it big in Hollywood.

When Joseph Vance Chorre Jr. switched between the mat and the silver screen, though, he was just trying to make a living. Known to wrestling fans for more than two decades as Chief Suni War Cloud, Chorre also appeared in nearly two dozen films, including a prominent role in Jim Thorpe — All-American. He was not the first Native American to wrestle or the first Native American to act. But, in either role, his pride and pageantry were always on display.

“He was a great guy,” remembered Dottie Curtis, wife of Don Curtis, who worked with War Cloud on the New York circuit in the early 1960s. “I always was awed by the bells he wore on the straps on his legs, and he had one of the most gorgeous headdresses. When he was moving toward the ring, it sounded like Santa and the reindeer coming into the arena. He was very impressive.”

The acting side came more naturally to Chorre. His mother Gertrude, born in 1885 on the La Jolla Reservation in California, was a character actress in her own right. A Luiseño fluent in the tribal language, she had more than 20 movie and TV credits from the late 1920s into the 1950s, and also was known as the go-to contact for producers who needed Native Americans for their movies.

Joseph was born November 14, 1914, in Los Angeles; reports of his early demise were greatly exaggerated, as the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record reported in 1920 that he was “perhaps fatally injured” when he fell 20 feet from the front porch of the family house on North Clarence Street.

From the start, he was a good athlete, twice competing in the Los Angeles Times Marathon as a teenager while attending Sherman Indian High School in Riverside. While attending Riverside Community College, he continued to act and earned his first role in the 1935 movie Wolf Riders. Mother and son acted together in several later flicks, including Flaming Frontiers (1938); largely uncredited, he was in several films with other family members, as well.

Chief John Big Tree, Gertrude Chorre, Sonny Chorre, Eleanor Hansen, and Charles Stevens in Flaming Frontiers (1938). Photo: IMDB.com

World War II put a hold on his career as he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1941 and wouldn’t appear in front of cameras again for about six years. Regardless, Chorre is “perhaps the most well-known California Indian from the early cinema period,” author Michelle Raheja concluded in Reservation Reelism.

By that time, he was embarking on a mat career as Suni War Cloud. Who exactly persuaded him to enter the squared circle is uncertain — wrestling lore claims Thorpe got him in the game — but all signs point to Los Angeles actor-wrestler Mike Mazurki, the first president of the Cauliflower Alley Club, who had a pipeline into the wrestling-cinema circuit.

War Cloud debuted in 1947 in California; his first matches were against Hans Schultz using an Indian versus German angle. Although he started late for a wrestler at 32, his showmanship and flair were perfect for televised wrestling and propelled him into star status for most of his career, primarily using chops and an Indian deathlock as a finisher.

His methods impressed onlookers, even if his physique did not. Bob Allen of the Chattanooga Times praised War Cloud after he disposed of Larry Moquin in a December 1948 contest.

“War Cloud, a spindle-legged, wasp-waisted, barrel-chested Indian from Brazil, took the crowd’s fancy in the semifinal on the card,” Allen wrote. “He entered the ring amid a roar of ‘war cries.’ He was adorned with a war bonnet of colored feathers that reached to the floor. And when he went to work, he proved a smart and colorful matman. The Chief knew the ways of the ring. In fact, he seemed more adept at the technique of wrestling than many grunt and groaners that have appeared on recent cards.”

In 1949, War Cloud mostly worked on Al Haft’s Columbus, Ohio-area circuit, with Jack Steele and Dr. Ed Meske as regular foes, before a run for Stu Hart in Stampede Wrestling in Calgary.

A 1949 photo of Suni War Cloud.

Starting in March 1950, the 235-pounder wrestled regularly from promoter Ed Don George’s Buffalo-based territory, where he’d appear on and off for 15 years, later for promoter Pedro Martinez and occasionally as a softball pitcher on Sundays for a team based in Akron, N.Y. “You know, if I wasn’t making the big money that I get for wrestling, I’d make a career out of softball,” he claimed.

Whether one could make a living from softball 60 years ago is doubtful. Wrestling was better for the pocketbook. His Buffalo main event in April 1950 against Frederick von Schacht, drew nearly 9,000 fans; a main event loss to Great Togo in 1951 brought in nearly 10,000 fans. In smaller New York towns, such as Binghamton, War Cloud was a consistent main-event attraction, as well, with LaVerne Baxter and Wee Willie Davis often supplying the opposition.

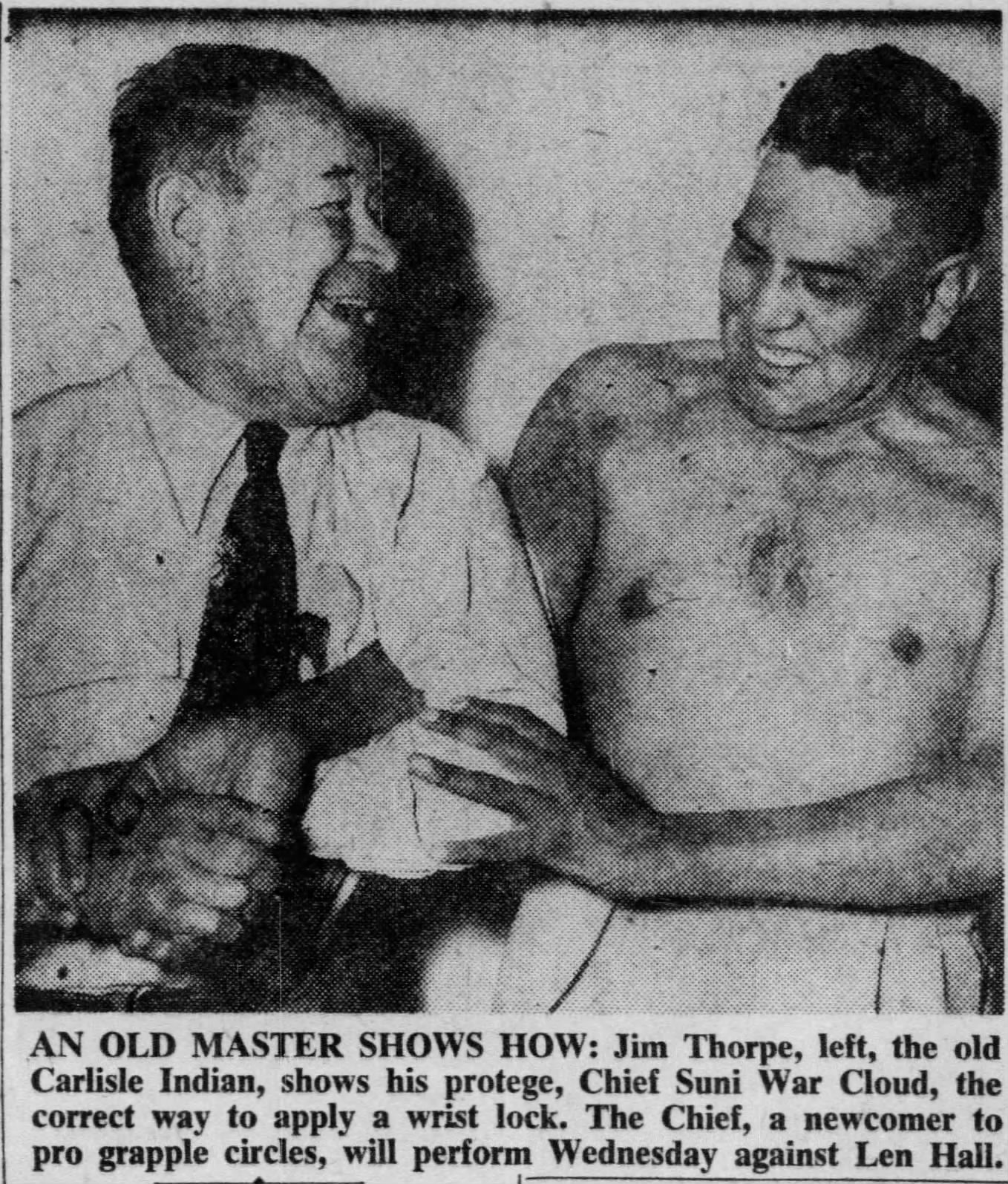

Thorpe was billed as his manager and appeared with him on a handful of occasions in upstate New York, reportedly getting $750 a week for his counseling, most likely from promoters and not Chorre. “With time on his hands in the evening, Big Jim would stroll up to the sports department of the morning paper and chat with reporters,” Syracuse, N.Y., sportswriter Jack Laing recalled years later.

But that duo was more consequential for other reasons — Chorre filmed the Thorpe movie, which starred Burt Lancaster, in 1951, earning his top screen plaudit as a coach named Wally Denny on the prowl for talent. “What am I gonna do for material? Half the kids think a pigskin’s something to eat for breakfast,” he cracked in one memorable scene.

Back on the mat, he had good runs in western Canada, Idaho, Tennessee, Northern California, St. Louis, and elsewhere before hitting New York during the early 1960s and feuding with Karl von Hess.

As was often the case, the hype surrounding War Cloud was overblown and obscured a very good, factual story. In the 1950s, various promotions billed him as a Mohawk Indian, born in Canada, and a one-time football player at Bacon [sic; it’s Bacone] College, a predominantly Native American Institution in Oklahoma. In Calgary, promoters claimed that he swam 18 miles from Catalina Island to the California coast in his heyday. That might have had a kernel of truth; his son Gary once told a reporter: “He personally told me about this on one of his visits to Albuquerque. He said you had to swim behind a boat with a kind of fishing net cage so that the sharks and stinging jellyfish wouldn’t get you. He said it was the hardest thing he had done in his entire life.”

Regardless, War Cloud didn’t need the embellishments. “War Cloud stole the spotlight,” the Syracuse Post-Standard said after a December 1950 victory over Larry Moore. Veteran Jerry Christy, who watched War Cloud in 1956 in the Houston territory, rated his war dance tops among all Native American wrestlers. “Nice guy, good guy, good worker. … He did the best out of all of them.”

War Cloud continued to dabble in the movies. He played in a couple of Joe Palooka flicks, got a role in Hot Summer Night, a pre-Frank Drebin Leslie Nielsen movie, and was an uncredited chauffeur in Tip on a Dead Jockey, a 1957 film starring Robert Taylor that took him to Spain for filming.

He was Sitting Bull during a swing through Europe in 1953-54, hit Australia, as well, and spent time as War Cloud in the Carolinas in 1966, frequently tagging with Billy Two Rivers. As Chief Crazy Horse, he wrestled well into his 50s in a few matches in Florida and Indiana. In all, WrestlingData.com credits him with at least 1,615 matches, though his championship gold was limited to a couple of minor titles in Idaho and Arizona.

Chorre died of a heart attack on January 14, 1987, in Los Angeles. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in nearby Santa Monica with brother Benny. In wrestling, though, the past is seldom forgotten. At least three War Clouds, ranging from Suni to Sunny, emerged during and after Chorre’s wrestling career. One, Pedro Valdez, followed the original into the Los Angeles territory just a couple of years after Chorre hung up his boots.

The treatment of Native Americans has changed dramatically in both wrestling and cinema since Chorre followed his mom into show business. But if his ability to juggle two high-profile careers is any indication, he would embrace the change and the renewed respect that comes with it. As one reviewer wrote of The Knockout, a Joe Palooka movie, “Suni Chorre is a man we wouldn’t cross.”

RELATED LINK