In 1988, a retired professional wrestler contacted filmmaker Jack Fritscher to pitch an idea for a movie. The wrestler wanted to make a film that would pull back the curtain on the secrets of the squared circle. He, however, didn’t want to reveal the usually guarded secrets like predetermined finishes that people already knew. He wanted to reveal the secrets of pro wrestling’s hidden homosexuality.

The movie wouldn’t be made for theaters. That’s not the type of movie that Fritscher made.

Fritscher isn’t a traditional filmmaker. Outside of directing, he authored a number of books including Leather Blues and Popular Witchcraft Straight from the Witch’s Mouth. His academic writing appeared in Bucknell Review and The Journal of Popular Culture. He was also the editor-in-chief for the gay publication Drummer magazine, which, according to the magazine itself, explored the world of “leather sex, leatherwear, leather and rubber gear, S&M, bondage and discipline, erotic styles and techniques.”

Fritscher wasn’t alien to pro wrestling. During his time at Drummer, he wrote a number of features about the sport. He even once authored an article about Hulk Hogan for another gay magazine.

“I contacted [Hogan’s] mother who sent me snapshots of the young Hulkster that were more personal and revealing of his hotness and his hairiness [than what was] revealed in the ring on TV,” Fritscher remembers.

Fritscher made movies for his company Palm Drive Video, which specialized in homomasculine gay erotica. The films focused on gruff, blue-collar models engaging in fetishes such as leather sex. The pro wrestler felt these themes suited him well.

That wrestler was the controversial Chris Colt, who lived a life of infamous exploits.

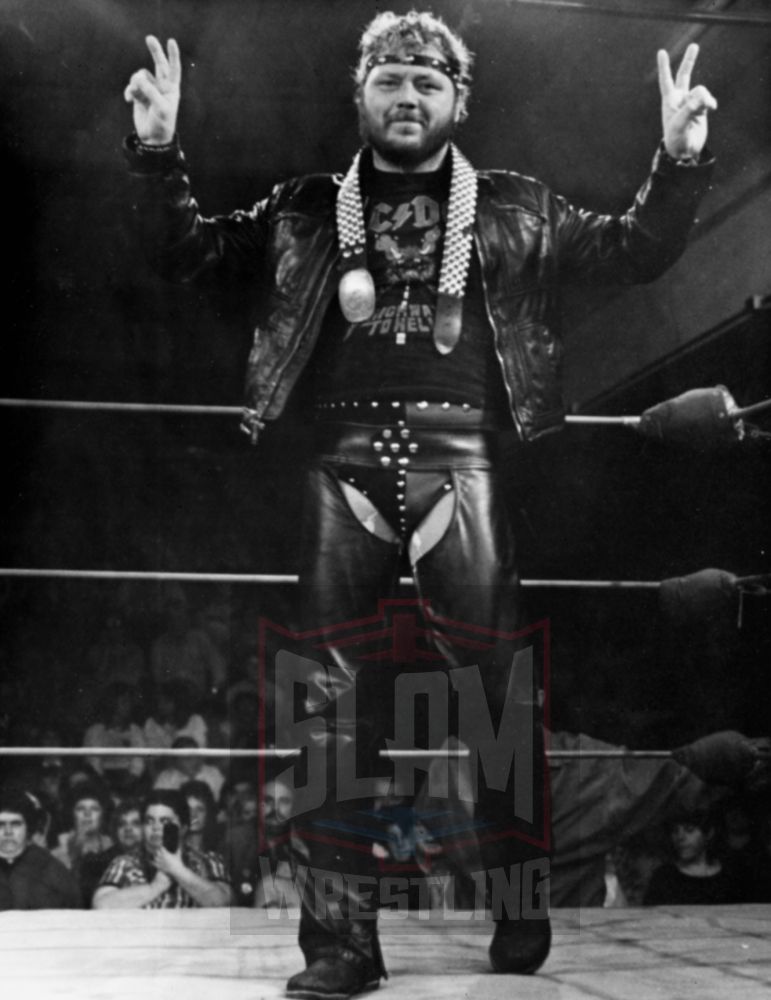

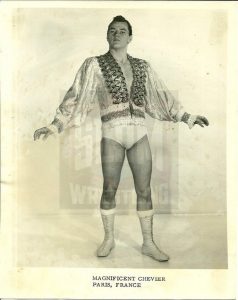

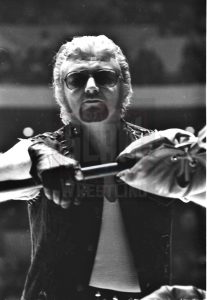

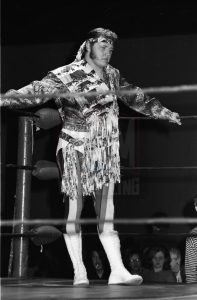

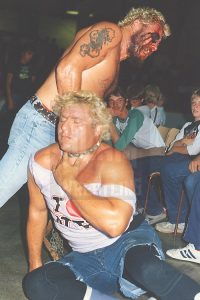

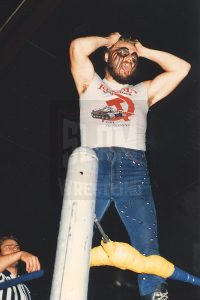

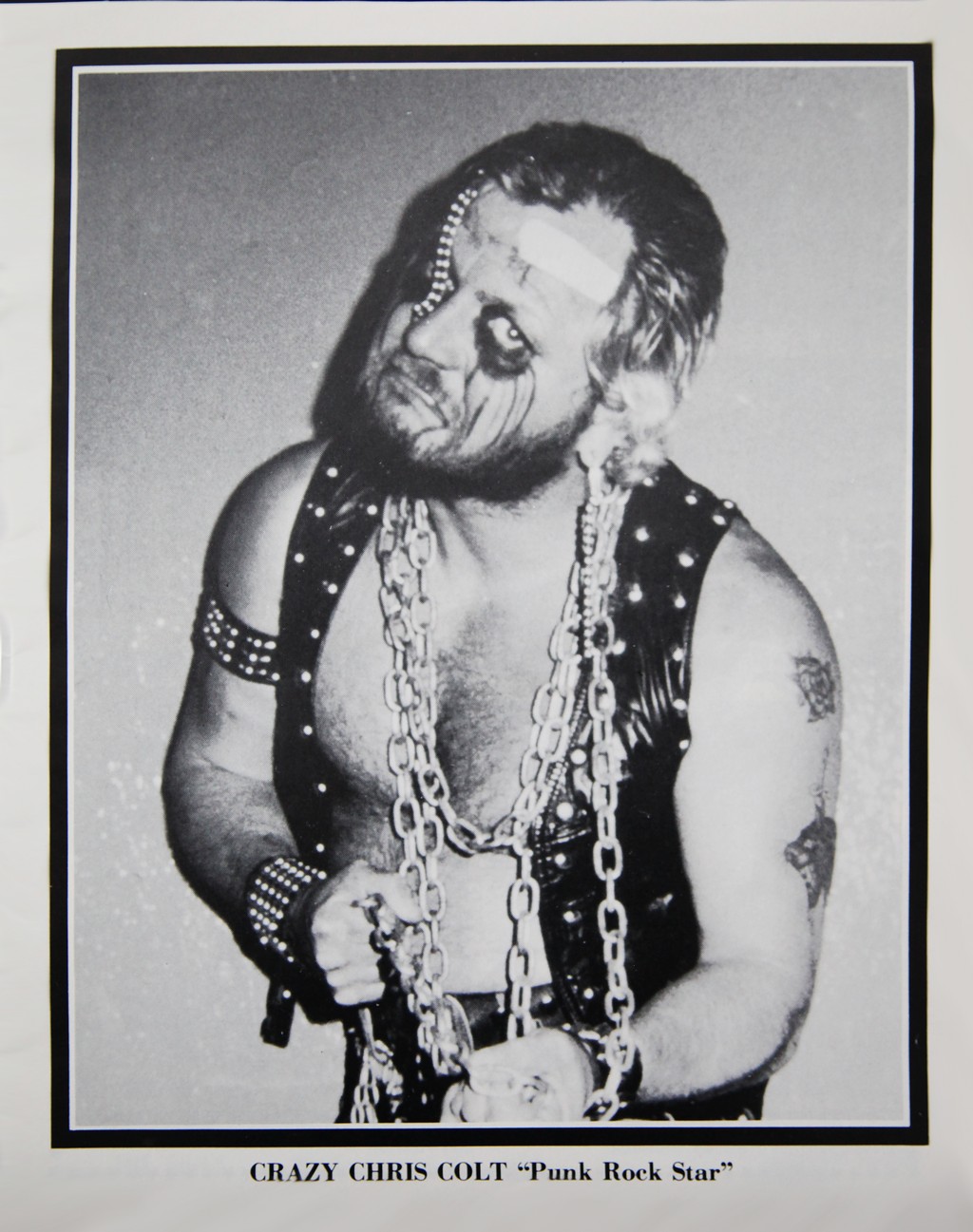

A Chris Colt publicity photo. Courtesy Palm Drive Video

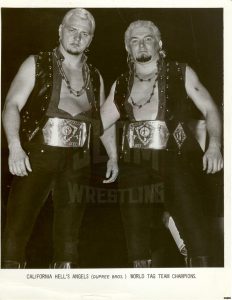

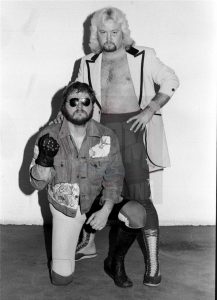

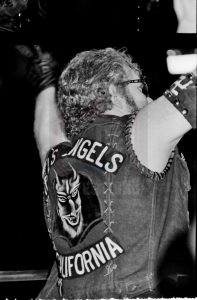

Chris Colt was born Charles Harris in the 1940s. It wasn’t until his family moved to Oregon that he caught the wrestling bug when he worked as a caddy for one-half of The Fabulous Fargo Brothers, Don Fargo (whom Colt would later tag with in The Chain Gang). He later found his way to New England in 1965 where he finally broke into the business as “Magnificent” Maurice Chevier. It was there that he met Russell Grobes. Colt changed his moniker to “Paul Dupree” and with Grobes as “Ronnie Dupree,” they formed a tag team of kayfabe brothers, known at various times as the Hell’s Angels, and the Comancheros.

Outside of the ring, Colt and Grobes were romantically involved at a time when homosexuality was even less accepted than it is now. They never hid their relationship from the locker room or the fans, but they didn’t want to advertise it either. The team and the relationship sadly ended in 1976 when Grobes died from a heart attack. He marched forward, changing his name to “Chris Colt,” which he took from Colt Studios, a company that produced gay pornography.

From then on, Colt seemingly attracted controversy everywhere he went.

He set fire to the American flag for a wrestling angle. He portrayed a neo-Nazi character. And he once hallucinated during a cage match due to him ingesting an unknown substance prior to the bout. This behavior could get him in trouble with promoters, and he was fired from territories on more than one occasion. No-showing scheduled bouts became all too regular.

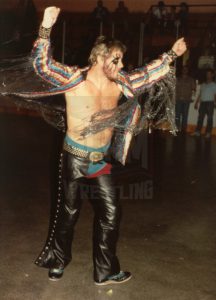

Colt even looked like trouble. Near the end of his career, his outlandish garb saw him decked out in piercings, Gothic makeup, leather biker vests, and safety pins inserted into his forehead. It mirrored his outrageous reputation and seemed fitting for a man who once served as a bodyguard for Alice Cooper. It also perfectly matched the aesthetic of Palm Drive Video.

Colt wanted to send a message to his former bosses, as well as to expose the hypocrisy of the industry. With his wrestling career behind him, Colt had nothing left to lose. He couldn’t fit in the cartoonish atmosphere of the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now World Wrestling Entertainment or WWE). He wouldn’t be welcomed into the dying National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) territories. And World Championship Wrestling (WCW), which would emerge from the ashes of those territories, also wouldn’t touch him.

Colt was a well-traveled veteran who worked for the NWA, American Wrestling Association (AWA), All-Star Wrestling, Southern States Championship Wrestling, Big Bear Promotions of Canada, and Joint Promotions in Europe, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. He wrestled Harley Race, Ric Flair, Randy Savage, Andre the Giant, Jesse Ventura, Adrian Adonis, Pedro Morales, Pat Patterson, Ray Stevens, and Jake Roberts. Yet time seemed to have left him behind.

“Chris Colt contacted me because he had reached a certain stage of maturity,” Fritscher says. “He wanted to slap his regional-wrestling circuit across the face for all the shit he had put up with in the ring and from management.”

Colt wanted his message to extend beyond just the promoters. He also took issue with his fellow grapplers.

“He knew that on set I would unleash him and let him do what he wanted to do precisely to piss off his peers, especially those pro wrestlers who are gay and closeted, and the worst ones, the pro wrestlers who are straight and homophobic,” Fritscher says.

Pro wrestling has two faces when it comes to homosexuality. One face depicts the overly effeminate villains like Adrian Street who prance to the beat of the crowd’s homophobic slurs. That’s the one seen on television, where the audience is conditioned to only cheer the heterosexual combatants.

The other face is the one hidden from the majority of fans.

“[Colt] wanted to pull back the wizard’s curtain on what he said were pro wrestling’s two biggest secrets: homosexuality and hustling,” Fritscher says. “Sex, paid for one way or the other, exists between some athletes, trainers, management, and fans.”

It’s a profitable side job.

“Hustling by pro wrestlers who put on private one-on-one shows posing for gay men in hotel rooms is big business in the underground world of homosexuality,” Fritscher explains. “That can mean that the marquee name does his pro wrestling act of muscles and trash-talk, often in full TV costume, while the ‘john’ masturbates.”

According to Fritscher, the crossover appeal of pro wrestling and the films of Palm Drive Video has much to do with their similar imagery, as well as the desire that men have to be immersed in masculinity. Both mediums share qualities that are simultaneously subtle, obvious, simple and complex.

“To the degree that TV pro wrestling is one of the main entertainments in American popular culture, gay videos likewise thrive on pro wrestling attitudes, fetish clothing, whips and chains, and alpha-male fighting action by homomasculine men who wrestle in gay videos as heels and jobbers, do the moves and the pins which are all done with an erotic man-to-man spin,” Fritscher explains.

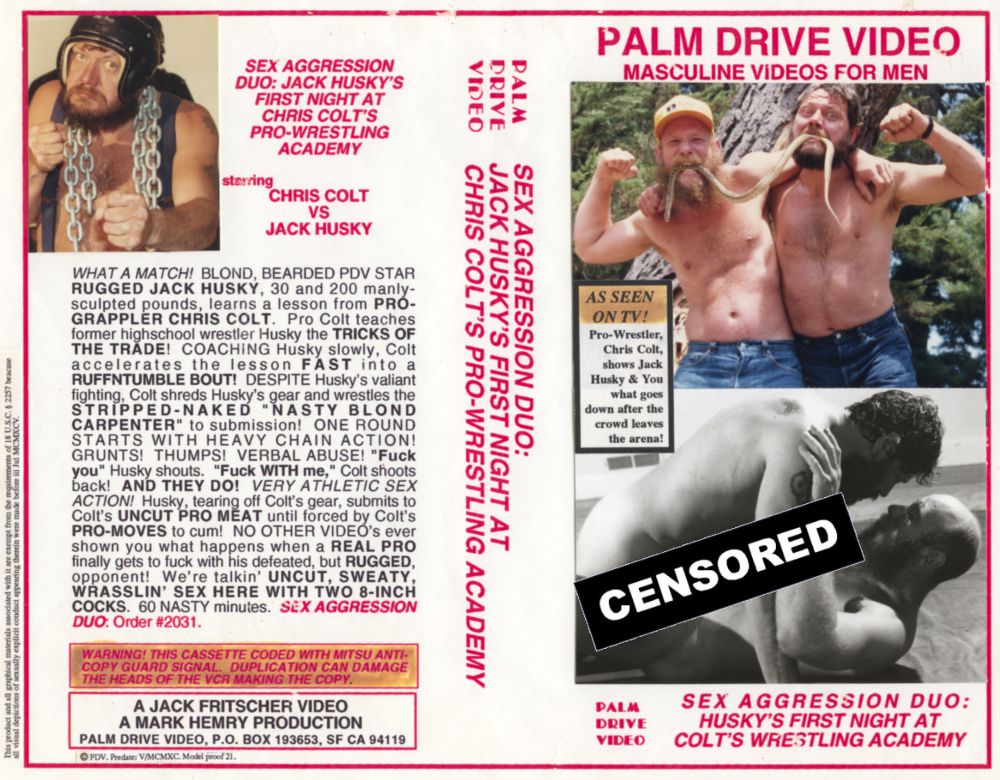

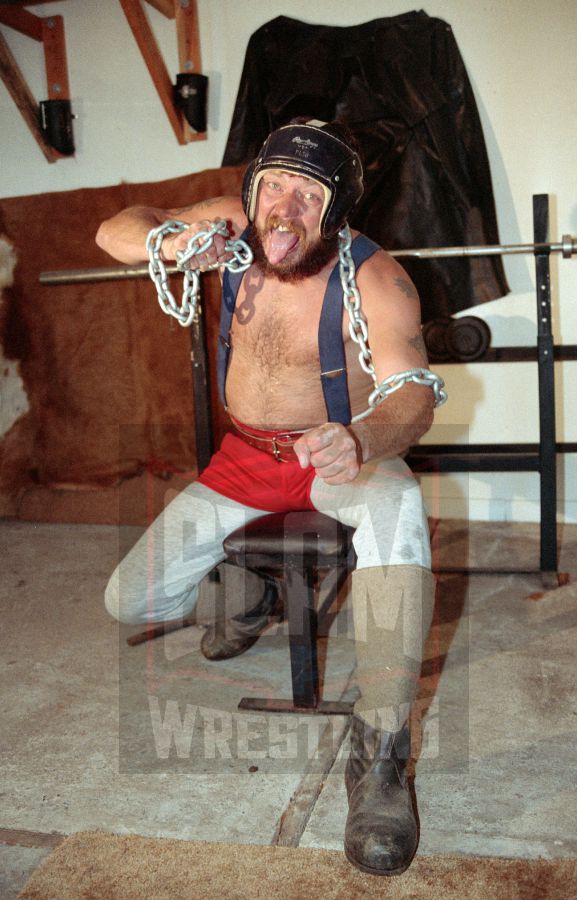

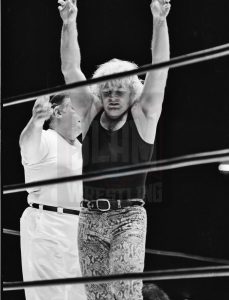

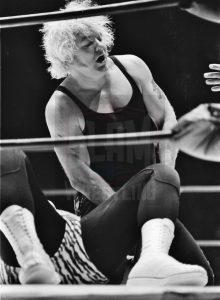

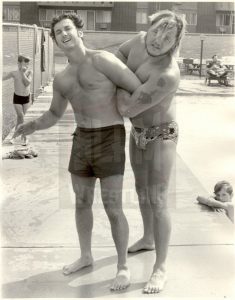

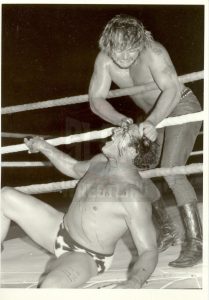

Chris Colt on set. Photo courtesy Jack Fritscher, Palm Drive Video

Colt made two films for Palm Drive Video, Uncut: Pro-Wrestler Chris Colt and Sex Aggression: Colt’s Wrestling Academy. His rough exterior was considered to be an acquired taste, and because of which, the videos appealed mostly to wrestling fans. Gay magazines of the time that wanted to feature a pro wrestling theme (popular among such publications) jumped on it too, running pictures from the films.

“Chris filled a needed slot: he was one of those men whose look was so tough and gross that it was all the turn-on of Beauty and the Beast,” Fritscher says. “To ‘refined’ gay men in love with received beauty, Chris had perverse appeal as the brutal man who is so ugly that he is sexy and, therefore, gets laid a lot as long as he stays in character.”

Colt’s films could be best described as surreal erotica. In Uncut: Pro-Wrestler Chris Colt, Colt begins by working out, the perspiration coating his skin until it glows in the reflection of the lights. He wrestles a masked opponent in a gym, often forcing the unidentified individual into suggestive positions.

As the film continues, Colt undresses while cutting classic wrestling promos with a sexual twist. He brags about how Hulk Hogan won’t face him, how Randy Savage stole the “Macho Man” name from him, and how he was the one who defeated Andre the Giant. He diverts his attention from challenging the superstars to verbally attacking fans and groupies, where he literally threatens to rip the audience’s penises off.

In the most avant-guard moment, Colt inserts a sharp object into his scarred forehead as if he were blading, leaving the object sticking out as he proceeds with his act. At the end of the video, Colt, now down to his leather underwear, masturbates and ejaculates when the other man caresses his genitals.

Colt only made two videos. He didn’t pursue it as a career.

“He was a specialty act and not particularly interested in being a generic gay porno star for other studios,” the director says. “He came to me because my erotic films are video portraits of the subject, catching emotive nuance that a still photo misses, but a freeze frame can capture. He wanted to see himself in a new way on screen.”

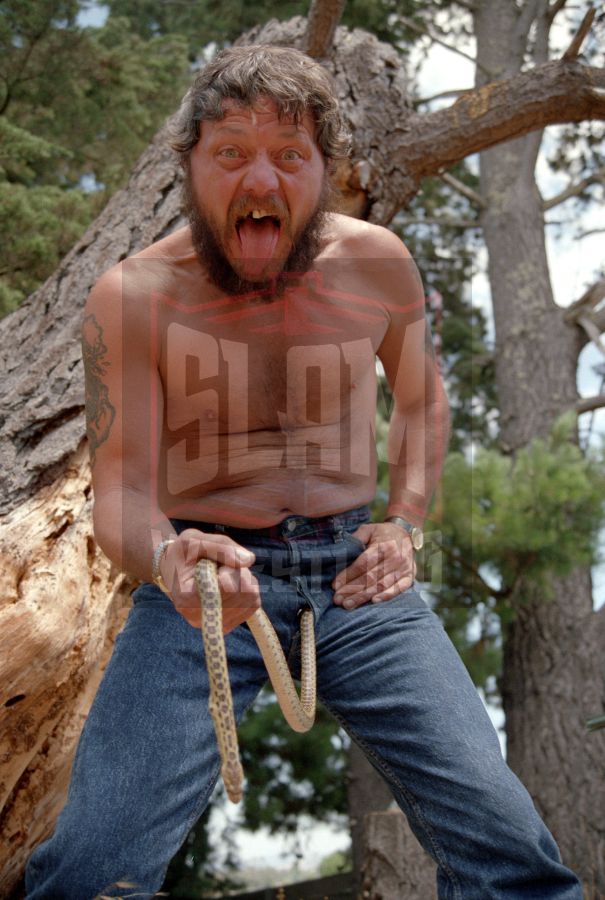

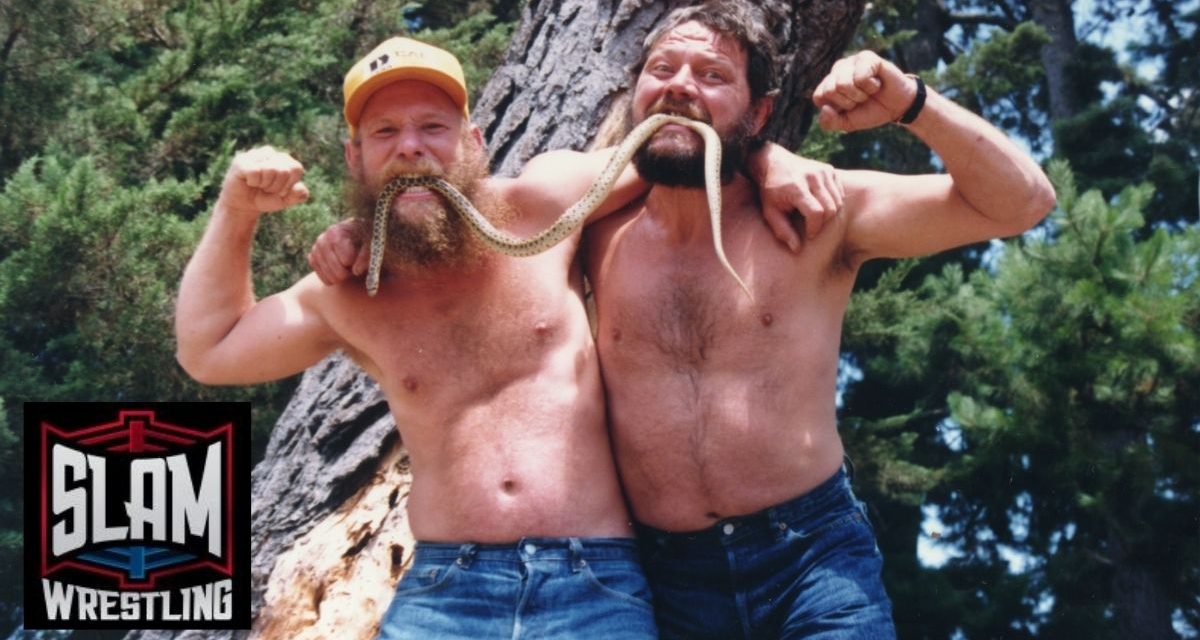

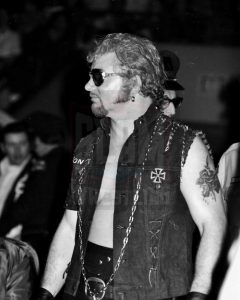

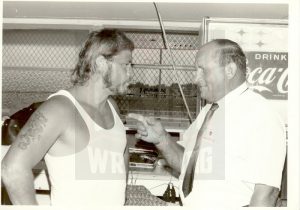

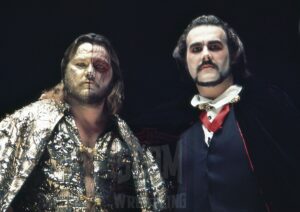

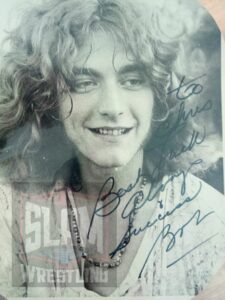

Chris Colt and snake. Photo courtesy Jack Fritscher, Palm Drive Video

Despite Colt’s hard-nosed reputation, Fritscher remembers the wrestler in a different light.

“Personally, Chris Colt was a joy, always smiling, and always aware that he was a pro wrestler because he was proud of what he did, and he knew his job made him a desirable sex partner,” the director remembers. “When I asked him to pose with a dead snake in his mouth, he creatively turned the moment into a tag team event and asked if Jack Husky, his co-star in the video, could hold the other end of the snake in his mouth. Of course, I agreed to this display of his showmanship so perfectly typical of over-the-top wrestling promotional photography.”

Colt’s life and career never recovered. He had a drug addiction that haunted him much of his life. His death in 1996 is shrouded in mystery, although rumors claim that he passed away due to AIDS in a Seattle homeless mission.

The struggles of the homosexual community, like those of Colt’s, may be why there is such a gay following for pro wrestling. While the visuals might play a factor, that’s only scratching the surface. According to Fritscher, the appeal goes deeper than that.

“Identifying with giant wrestlers makes oppressed and intellectual gay men feel empowered, especially during an economic downturn when men whose jobs are shaky turn to their own muscles and to those of other men to prove they are in power and control even though unemployment threatens,” Fritscher says.

While Colt’s life faded away, pro wrestling hit milestone after milestone. In 1988, the WWF ran WrestleMania IV, which saw a rematch from 1987’s hugely successful WrestleMania III between Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant. The event also crowned Randy Savage, Colt’s former adversary, as the WWF World Champion.

It was far from reality that Colt lived. While Hogan provided escapism, taking a turn as a thespian in movies like Mr. Nanny, Colt projected the uncomfortable truth in his films as he fought for his dignity and basic survival. The mainstream may have ignored Colt’s contribution, but it doesn’t diminish what he set out to accomplish. Colt’s message is finally being heard.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Curious readers may enjoy the new Palm Drive Video documentary titled Raw! Uncut! Video! A Fetish Love Story premiering now in international gay film festivals.

RELATED LINKS

- Fritscher, Jack, “Shooting Chris Colt.” April 2021, at www.jackfritscher.com

- Apr. 9, 2024: Chris Colt maybe the darkest ‘Dark Side’ yet

- May 11, 2021: Mat Matters: When Chris Colt met Joe Cocker

CHRIS COLT PHOTO GALLERY

I saw Colt, Magnificent Chevalier, many times and his mate Ronnie Dupree the Golden boy, at Jack Witchi’s, Sports Arena, N. Attleboro, Mass. Under the tutelage of Tony Santos, owner of Boston Arena-based Big Time Wrestling, before they ventured to the big time so to speak in Ohio as the Hells Angels. Wild Bull Curry was also a star with Santos and a huge star in Ohio in such cities as Dayton, a huge wrestling hotbed circa 1964 to ’67. They hung out with another gay mate known as Haystack Muldoon — a rip-off of Haystack Calhoun. Santos and a fellow promoter Jack Pfeffer were known for this close name rip off advertising! When in Boston, I believe the only gay bar in the city was the Punchbowl. Santos had warned them several times about going there, stating fans did not want to pay to see a bunch of queers fight! Thus there leaving the area for good, and far as I know never returning!