Rick Steiner’s career has been one of happenstance.

Steiner, who earned second place in the 1983 Big Ten Championship, grew up in an amateur wrestling state of mind, but never had plans to set foot in the squared circle.

The amateur bug hit when his and Scott’s father took them to a wrestling practice while in elementary school. But they were “always kind of physical.”

Jerry Brisco and Rick Steiner after Rick’s induction into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in Waterloo, Iowa, in July 2014. Photo by Joyce Paustian

“My mom went and got us like about six or seven different pieces of carpet. They were about about 20-foot-by-20-foot, and we put them in the basement,” Steiner said, “and we stacked them on top of each other and we made a little mat and we brought all the neighbour kids over and tried to beat the crap out of them.

“So it started like that, and then we wrestled each other. And it was kind of funny because it got to be a joke for the neighbour kids — if everybody had rug burns on the side of their head or on their elbows or on their knees and stuff, everybody knew that you were over at the Steiner brothers’ house wrestling around.”

But setting the course for an amateur career in eighth grade was where the plan ended.

“I didn’t watch [pro wrestling],” Steiner said. “I knew it existed, but it wasn’t something that I had any interest in or anything.”

The Dog-Faced Gremlin earned a bachelor of science in education from the University of Michigan and was substitute teaching when he returned to Michigan to help with amateur wrestling camps. Through that venture, Steiner met George “The Animal” Steele — who was a teacher when he wasn’t ripping up turnbuckles with his teeth — and his journey to the pro ranks began shortly after.

Steiner traveled to Minnesota for an AWA training camp and was taught by Eddie Sharkey and Brad Rheingans.

“It was like the unknown… and everyday you learn something and something would click and you would catch on,” Steiner said of the training environment. “So that was the spark that kept me interested in doing it.”

But it took about three to five years for him to adjust from an amateur mindset and learn ring psychology. The Dog-Faced Gremlin said he “was always serious and gung ho and, ‘Go out there and let’s just tear some bodies,’ and you can’t do that.”

“One-hundred percent of the guys that went out there, heck I could, if it was real match — shoot — take ’em down and beat ’em up and pin ’em, but that’s not the way it is, and it’s entertainment,” Steiner said. “So I had to learn the psychology and the entertainment part of it. and it just takes a while.”

Once he completed the camp, Steiner spent eight months in Montreal, Quebec, working for Tom Zenk, Gino Brito and Dino Bravo at International Wrestling. As such, his main-event appearance Saturday with Great North Wrestling will be a homecoming of sorts when he challenges Hannibal for the GNW Heavyweight Championship in Robert Hartley Arena in Hawkesbury, Ontario, halfway between Ottawa and Montreal in the old International territory.

“Montreal was always a great city and especially — I lived in the Italian side, but it was a great city to be apart of and be in,” Steiner said.

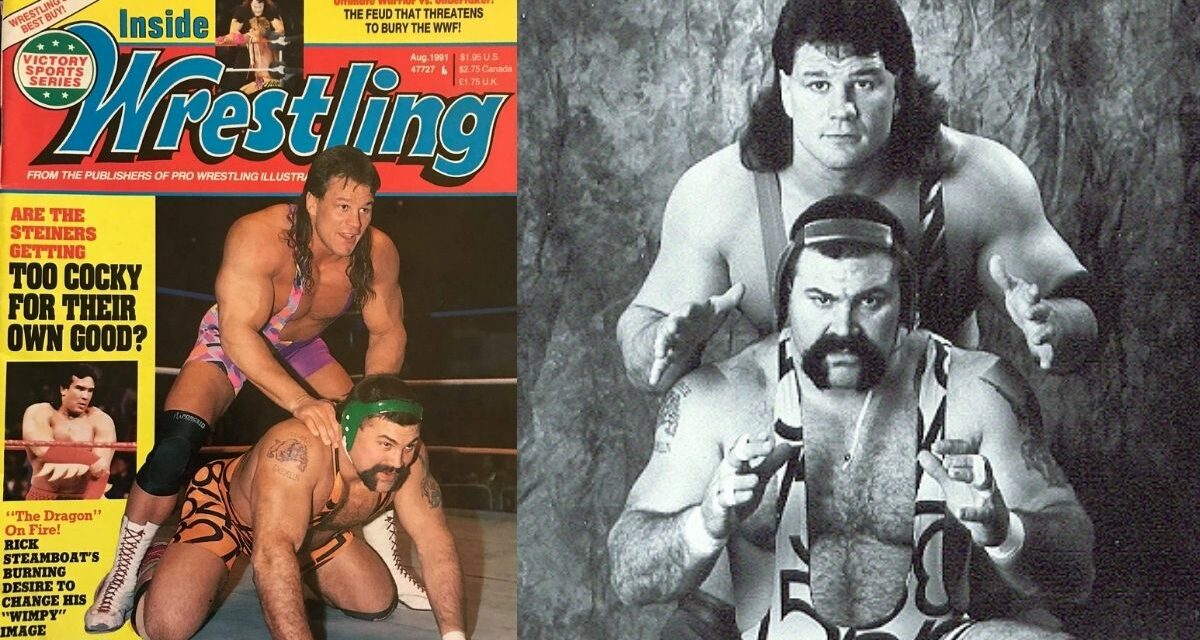

Rick and Scott Steiner in 1989. Photo by Howard Baum

THE STEINER BROTHERS

The Steiners started teaming together in 1989 and, in addition to the natural chemistry of bloodline brotherhood, they also had added confidence from their amateur wrestling background.

“It was real easy as a team for us to gel and make things happen,” the older Steiner brother said, “because just being together that long, I knew what he was thinking. I could tell when he was mad, I could tell every expression where he was at.”

In traveling around the U.S. — working for WWE, WCW and ECW — and making the rounds with New Japan Pro Wrestling, the duo racked up 14 championship reigns.

But, as can be the case, the Steiners were eventually separated. WCW broke up the brothers in the late 1990s. At the time, Steiner said, he “wasn’t real sure what was going to happen.”

“We were at a that point we’d wrestled everybody, so something had to happen,” Steiner said, “and it just worked out for my brother that at that point he kind of made a transformation and he did his thing, and I kind of changed up my deal a little bit, but for for the most part I kind of stayed the same, kept that rough kind of persona, and just kept going with that until WCW ended up having to sell.”

The younger Steiner morphed into “Big Poppa Pump,” and aligned himself with WCW’s New World Order in the years leading up to Vince McMahon’s purchase of the company.

Having worked in most every major company at the time, Steiner said he enjoyed “learning and teaming with Sting,” but the “best time was with WCW.” There, the Steiners were established, known, and making money.

“If I had to pick one, it would be WCW,” Steiner said. “It was just so much fun, the concept [WCW owner Ted] Turner had of keeping it family. And then he looked after us, took care of us as entertainers and athletes, and it was just a better, wholesome environment to work in. And I learned a lot.”

While he has accolades both on the traditional mat and between the ropes, Steiner doesn’t consider one more successful than the other.

“My brother and I were successful in amateur, but that gave us the credibly in the professional ranks to excel and do some of the things,” Steiner said. “Suplexes have been done for 100 years before we even got in the business — and there [were] a lot of things that were done in the business before we got there — but I think the added aspect of my brother [and I] being actual amateurs and being All-Americans and giving the moves and what we were doing some legit credibility, I think that’s what helped us.”

But the Steiner Brothers style, according to Rick himself, could be “pretty rough.”

“Sometimes we got complained about,” Steiner said. “It wasn’t ballet, and we treated it as a competition. And that’s where I think Japan really helped, or was a great fit, for my brother and I because that’s the way they liked it. They liked the contest, and they liked it rough and they wanted all that amateur mixed in with the professional.”

Rick Steiner

OUT OF THE RING

While trading blows in the ring, Steiner teamed up with Big Boss Man, Curt Hennig and Rick Rude to get in the real estate game — buying and selling properties to build a “nest egg.”

“[Boss Man] was getting some million dollar properties and getting ’em cheap just because of who he was and he knew the system,” said Steiner, who earned his real estate license in 1995.

And that’s a business venture he still clings to today with Rick Steiner and Associates, working with a variety of properties from residential to farm and lake locations.

“I come across the first-time homebuyers to the people who are downsizing in later years in life. So that part is fun to be involved with and give consultation,” Steiner said, “and then it’s just different. It’s something new every day with different houses, different architecture, seeing different ways people live and their houses and ideas for my house.”

He likes the atmosphere for the ability to choose his own hours, not being “stuck to a desk” and having total control over his income.

“There’s no real ceiling, there’s no cap on the money,” Steiner said. “I can make as much as I want. I can work as hard as I want. It all comes down to me, and I like that.”

Steiner also has traded in the singlet for a suit, as he’s been a member of the Cherokee County School District (Ga.) Board of Education for more than a decade — a position he also came into by happenstance. When a board member’s departure left a vacancy, friends who were teachers encouraged him to seek the open seat.

“It’s a chance for me to give back the area, the community I’ve been apart of now for 26 years,” Steiner said. “I had three boys go through system, so it’s a chance for me to give back and make sure that I leave the county that I moved to here, just leave it in a better spot or better position than what we started off at.”

RELATED LINK