Frank Luhovy, who died May 24 and wrestled as Frankie Lane, always wanted to be a cowboy, and it took a blind promoter to see that he was the right fit.

In the late ’60s, having wrestled for just a few years, Luhovy headed for Leroy McGuirk’s promotion in Oklahoma.

“Leroy McGuirk was, of course, blind, but he had a good perceptive image of each individual person just by the way you sound,” Lane recalled in 2001. “I told him where I wrestled and all that. I said, ‘I’d like to wrestle as a cowboy.’ He said, ‘Got yourself a vest and a cowboy hat?’ I said, ‘Nope, but I can get them.’ He says, ‘Okay, if you want, you can wrestle as a cowboy.’ It was that easy.”

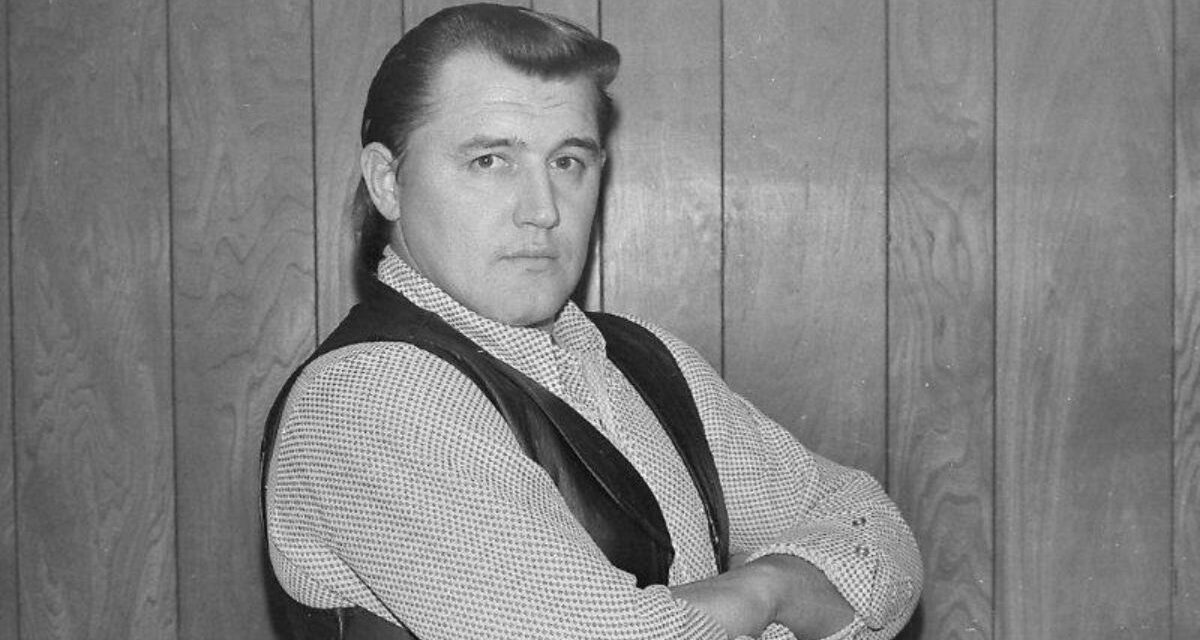

A young Cowboy Frankie Lane.

Wearing the outfit and the cowboy boots, “Cowboy” Frankie Lane — named after the popular singer, which was spelled “Laine” — hit just about every territory there was, except, ironically enough, Texas.

Born April 16, 1943, and growing up on a farm in the small Ontario community of Alvinston, Luhovy saw wrestling as an opportunity to get away.

“I was working in Windsor for the Ford Motor Company, and they had a school in Detroit for pro wrestling. I attended the school there, and got the experience enough to start doing TV wrestling and stuff like that. When I had enough experience, I quit my job in ’68,” he said. Others at the training camp were Ricky Cortez, Abdullah the Butcher, Wild Bill Norris, and “Crybaby” George Cannon, and Gino Brito was a trainer.

His first stint on the road came for the AWA, where he and Billy Red Lyons were teamed and started to get a decent push. But it ended abruptly when he ran into border issues.

“My visa ran out and I didn’t go fill it out. I went across the border and they asked me where my visa was. I told them Detroit. They said I’d better go down there and get it and renew it. I got back to Minneapolis, and things weren’t the same because I was gone too long,” he explained.

Though he used a mask a few times — the Red Shadow — it was as Lane that he is best known.

He hit almost every territory in North America, and almost 30 countries, including Japan, Australia, Puerto Rico, and Germany, during his career.

There was no question he had the looks and skills to be a star. “This Lane,” promoter Herb Welch said in 1976, promoting a show in Blytheville, Arkansas, “is very promising. He’s the sort you look at and think he’s capable of being champion someday.” But he never quite hit the main event status.

There were dozens of titles during his career, including the Pacific Northwest tag belts on two occasions (with Moondog Mayne and Jimmy Snuka), the Hawaiian title, singles and tag titles in Los Angeles, and the Stampede Wrestling North American Heavyweight title on two occasions.

“Over the years the name ‘Cowboy Frankie Lane’ has become one of the most respected and idolized names in the sport of professional wrestling,” reads a 1984 program. “Frankie Lane is one of the most dynamic wrestlers in the world. The admiration he receives is justly deserved.”

“Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe worked with Lane often in Charlotte, and the proof is still inside of him.

“He thought he had the best chops in the business. He had a very good one,” said Sharpe. “He hit me so hard and so often that it tore my pancreas. That’s something that you can’t fix.”

The biggest crowds he worked for were probably in Puerto Rico, where he and Dutch Mantell teamed to championship acclaim.

“When I was in Puerto Rico, I went down there with Dutch Mantell, and we done real good there. We sold out the Roberto Clemente Coliseum a couple of times and the ballpark, we drew, I don’t know, 40,000 people there, which was unheard of at the time,” he said.

As well as being recognized as a good hand, Lane also had a hand in getting Abdullah the Butcher started — he’d known Larry Shreve from the Vic Tanney’s gym in Windsor — and Jimmy Snuka, who he befriended at Dean Higuchi’s gym in Hawaii.

“Everyday that I wrestled was a learning experience. You just never stopped learning. Of course, as you got the experience, you become more noticeable to the promoters, that they might be able to do something with you, either give you a belt, team you up with a tag team partner and go for the belts, championship tag team belts, or whatever,” the 6-foot-1, 235-pound Lane said. “You never stop learning almost to the day you quit, because it’s the type of business that each individual person is different.”

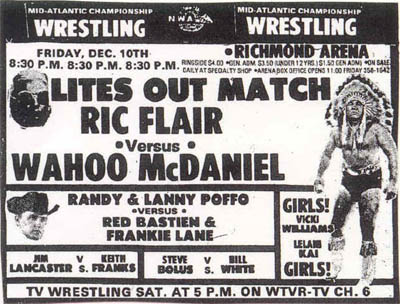

Richmond, Virginia, December 10, 1976

When Lane’s name is brought up with his contemporaries, the story of his fight with “The Magnificent Zulu” Ron Pope often comes up; it’s one of the most famous backstage incidents in wrestling lore.

He had a scar atop his head for the rest of his life after Pope fractured his skull in the late-’70s.

“He went nuts because I wouldn’t drive him to the next show. I was sitting in the seats and he hit me with an iron bar. He got away before the cops arrived. I was in hospital 17 days,” Luhovy told Jim Kernaghan of the London Free Press.

Detroit veteran Big Jim Lancaster shared what he had heard in 2003 with CWFArchives.com.

“Bobby Blaine of Klein’s Gym was part of a group of guys who were heading to Akron, Ohio, for a show for Sheik. They were to meet in Toledo and ride together. It was Blaine, Zulu, Lane and Bull Curry. For whatever reason, Lane and Zulu had a falling out, according to Blaine. Lane drove by himself and Zulu drove Curry and Blaine to Akron. Blaine said the entire trip that Curry kept telling Zulu that he would never let a man talk to him like that, that Zulu was a coward and that racism was involved. Blaine said Curry instigated the whole thing. Blaine did not witness the attack, but supposedly Zulu hit Lane with a pipe while he was behind a curtain watching the matches from a stage. Zulu then ‘left the building’ leaving Blaine and Curry behind. Lane was hospitalized for a long time over that.”

In the 1980s, Luhovy stuck pretty close to home.

“My dad just got tired of working the farm all by himself. He said, ‘Come on home, give me a hand.’ My brother was in banking, my sister was a schoolteacher. It was just him and my mom taking care of the farm,” he said of the family homestead, where they grew soya beans and wheat. “They had 400, 500 acres already then. So I come home and start working here for Jack Tunney and Eddie Farhat, The Sheik.”

He also gave promoting a try himself.

Frankie Lane in the 1980s. Photo by Terry Dart.

“I ran a few shows on my own, but you know you can’t fight city hall,” he said, noting how the Tunney family controlled Ontario. It’s the same reason that he had to hit the road to make a living, he said. “When you’re a local guy, they don’t give you a break like they should. For the amount of talent that I had, I wasn’t exploited properly.”

Luhovy quit in 1989 because he had a car accident, breaking six ribs, an ankle, and messing up his back.

Besides working on his farm, Luhovy ran a few wrestling schools here and there, and was associated with a few others.

“The guys, they ain’t got the money,” he recalled. “They say they want to do it, but it ends up that you’ve got everything organized, got the gym facilities … I had lots of gyms in different areas, but they didn’t have the money. So what are you going to do? Your expenses keep on going, so I closed it down.”

Frankie Lane in 2009. Photo by Shuhei Aoki

He was asked in 2001 if he missed the wrestling business.

“In one way I do, and in another way I don’t because it’s not the same as it used to be years ago. … There was always envy, jealousy, but it wasn’t to the degree that it is now,” he concluded. “The guys who do jobs to guys to put them over make more money than the guys in my time that we champions did on top. The money is just unbelievable. I can’t begrudge what wrestling had done to me. I’ve been to a lot of places, different parts of the world, met a lot of different people. I liked travelling. Now as you get old, you just want to settle down.”

For the last number of years, Luhovy, who suffered from Multiple Sclerosis as well as from his wrestling aches and pains, was confined to Fiddick’s Nursing Home in Petrolia. Mass for Luhovy was celebrated on Friday and he is buried at St. Matthew’s Cemetery. He is survived by his sister Mary Lambrech (late Lee) and his brother John Luhovy, niece Anita Quenneville, and nephews, Michael Lambrech (Trudy) and their daughter Kendall and Philip Luhovy and long time friend Ken McKenzie.