I called Billy Wicks up in the summer of 2007. He’d taken a wicked header down the stairs a week earlier and was black and blue. He described it as the worst bump in his career as a wrestler.

At the time, Billy was in his mid-70s. His mind was sharp but his body was failing him. Many years earlier, he had broken his neck doing wrestler’s bridges and had to have metal rods surgically implanted on his vertebral column (Billy would always caution you, or more accurately, admonish you, not to do them). That, coupled with a litany of other chronic injuries from his involvement in pro wrestling, had taken their toll. However, what he accomplished, even during these years of chronic pain and highly limited mobility, was remarkable.

I learned about Billy Wicks’ career through Scott Teal’s fantastic Whatever Happened to…? series and was further encouraged by historian Mark Hewitt to get in touch with him. Like Mark, I had developed a strong interest in the early days of professional wrestling in North America. In particular, I was interested in what is commonly known in the world of professional wrestling as “hooking:” the submission elements of the historical art of professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling.

The ability to effectively apply injurious holds against a resisting opponent and make him “cry uncle” was a skill set that hearkened back to the early 20th century: a time before the territory system had developed. Many wrestlers of the era managed their own bookings and acted as autonomous, freelance athletes. The flip-side to autonomy was uncertainty. Although many matches were co-operative affairs, some were not. Wrestlers had to be ready. Certain wrestlers were far more than ready. They were, in the words of wrestler Frankie Cain, “engines of human destruction.” Some wrestlers of the time also wrestled in private, either for side bets or to settle business disputes (or both). Some wrestled in carnivals and were compelled, on occasion, to take on challengers from the audience. Some did all three.

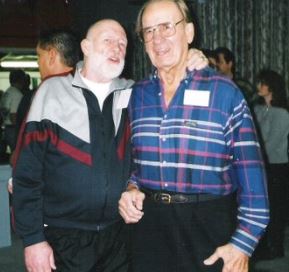

Billy Wicks and Lou Thesz

By the time Billy Wicks came of age in the 1950s, the territory era was in full swing. Going against the booker would be a fast trip to the unemployment line. Public shooting matches just did not happen. However, Billy got his start in the pro ranks on the carnivals, where they still could.

There had always been great amateurs, frequently college athletes, who made the transition to the pro ranks, but the ability to not only pin or score points, but also “hook” an opponent, was a different matter. This was not taught in colleges. Billy, who had already been an amateur, learned the art from grizzled old athletic anachronisms such as Doug Henderson and Henry Kolln: men who had got their start back when people were still openly gambling on pro wrestling matches. Billy said they taught him to get the job done fast. If an outside challenger had to be faced, there was no messing around. Carrying a guy for too long increased the possibility of danger, and if it was a “dollar-a-minute” match, it meant that the company might have to pay out too much money if the contest dragged on. Plus, matches like that could kill business.

When I made Billy’s acquaintance, the art of professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling, already fading when he himself was a young man, was virtually extinct. A lot of wrestlers did not pass those skills on. Many were secretive. They reasoned that they might have to face whoever they taught at some point, and they did not want to end up wrestling themselves. For others, the skills were viewed as unnecessary. They didn’t see the point in passing them on, and quite frankly, later generations of pros did not see the need to dedicate the sizable amount of time needed to master them, either.

I have watched with sadness as the “old guard” of authentic professional catch-as-catch-can wrestlers has died out. England’s Billy Joyce and Tommy Moore. Then Karl Gotch. Then Billy Robinson.

Billy Wicks was pretty close to being the last of his era. Now he’s gone, too.

Fortunately, unlike many who predeceased him, Wicks, similar to Billy Robinson, was very open with sharing his knowledge. Wicks was not flowery in his approach. He came from working-class Norwegian roots and made no pretensions to being a university-educated kinesiologist. He explained things in simple terms. A solid mastery of basic wrestling was the foundation for catch-as-catch-can. Get good at escaping from the bottom with sit-outs, switches and side rolls. Add to that three fundamental submission skill sets: headlocks, toe holds, wrist locks. Forget hours of extra conditioning. Learn to relax. Drill, drill, drill and wrestle, wrestle, wrestle. And get off your damn back!

Sounds simple enough. Yet, beneath Billy’s very straightforward expression of wrestling’s underlying principles was a vast and deep well of knowledge, passed down to him by the likes of Henry Kolln, who had, in turn, learned his craft from the father of American catch-as-catch-can wrestling, “Farmer” Burns.

By the last decade of his life, when I knew him, Billy Wicks was like the proverbial knotted, withered old tree whose faded frame belied roots anchored deep into the earth. In Billy’s case, his roots anchored him deep into this continent’s wrestling past, to a time when not only the ability to “show” but also to “shoot” counted for a great deal. And it was during this last decade or so of his life that he made his greatest, and likely longest lasting, contribution to the annals of American wrestling history.

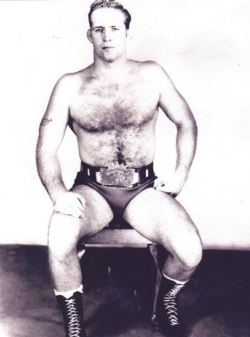

Billy Wicks in his prime.

Retired in Waynesville, North Carolina, people began to seek Billy out. A growing interest in submission wrestling and the rapid dissemination of information via the internet led people to wanting to learn the ins-and-outs of authentic catch-as-catch-can wrestling (what Karl Gotch would call real pro wrestling). A few people, with an eye for a potentially untapped market, came out of the woodwork at that time alleging to know this kind of stuff. But Billy, undeniably, did. Long away from being an active participant in the wrestling game, and with serious physical limitations, Billy once more took to the mat. This is where, to a growing cohort of young and enthusiastic athletes, he became affectionately known as “Pops.”

Though limited in his mobility, much like Billy Robinson, Pops would coach from the sidelines, and while still able to, get down on the mat to demonstrate what he could. Men such as Jon Strickland, for whom Pops became like a surrogate father, as well as Johnny Huskey, spent years at his side and continued to learn from him even after advancing physical deterioration meant that he could no longer make it to the gym. Pop’s skills speak for themselves through, for example, the abilities that dedicated students show in the MMA cage and on the mat. For those, like myself, who maintained regular contact but never had the blessing of meet him in person, Pops would send videos of technique and offer advice and stories about his days in the wrestling business, always in his characteristically straightforward way. Pops was all substance and no flash. He never asked for a penny for his time or his resources. I never had the honour of being his student, but I counted him as a friend and one of the most fascinating men I have met.

And what a sense of humour he had. Even in his 80s, he could make a marble statue blush.

In the annals of professional wrestling, Billy Wicks carved out a modest, but memorable, legacy. For a time, he was the biggest thing in the Memphis territory, and his feud with Sputnik Monroe will be recalled by diehard fans for the record number of people it attracted to the ticket window. However, his greatest legacy will be in preserving, and ultimately helping to re-promulgate through a cohort of dedicated students, a fascinating piece of American sporting history. Pops never set out to do this. But a lot of people with an interest in the now rapidly growing art of catch wrestling are thankful that he did.

RELATED LINKS