While there were thousands of matches in the wrestling career of Jimmy Buckle — mostly as midget star Lone Eagle — few compared to the first one at home, in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, where they were packed to the rafters at the Humber Gardens.

It also happened to be his mother’s birthday.

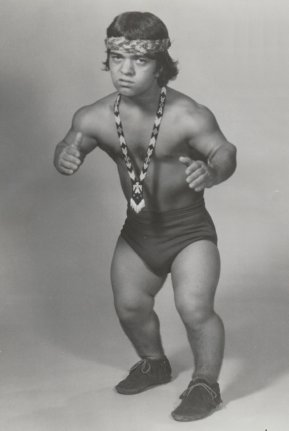

Jimmy Buckle in a publicity shot for Chief Lone Eagle. All photos courtesy Jimmy Buckle.

“The place was jammed. There wasn’t an empty spot in the place,” recalled Buckle from Auburn, Kentucky, his home for the last 32 years.

The show on August 7, 1979, promoted by “Crybaby” George Cannon, featured the likes of Bulldog Don Kent, Big Mac, Luis “Arriba!” Martinez, and the biggest star ever from Newfoundland and Labrador, Sailor White.

It was Martinez who turned to the teenaged Buckle and told him, “Buddy, this is your show, this is your house tonight.”

Jimmy teamed with Farmer Pete against Little John and Cowboy Lang.

“This match had the mood of the crowd changing from hysterics to crying. But in the end it was Jimmy and Farmer Pete who came up the winners,” reported The Southern Gazette.

Gary Kean was one of those fans, a neighbour of the Buckle clan, about 10 years younger than Jimmy.

“I happened to be on the street outside my house when his father’s red pickup truck came by, with Jimmy in the passenger seat. I remember seeing focus and pride in his eyes and a big grin on his face. He was so happy to have had this opportunity to wrestle in Humber Gardens,” recalled Kean, who went on to a newspaper writing career.

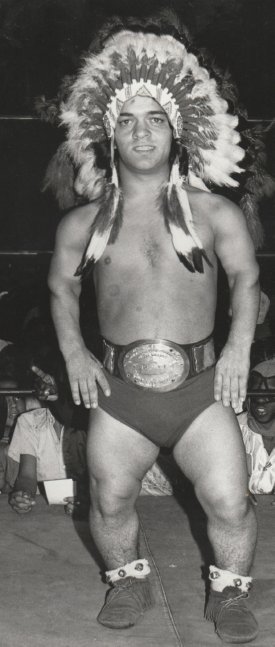

Though he was Chief Lone Eagle — a name given to him by his trainer, Lord Littlebrook (Eric Tovey), because of his darker skin colouring — and wore an Indian headdress to the ring, doing a tribal dance before the match, he was still Jimmy Buckle, pride of Corner Brook.

“The crowd was there to see Jimmy. He had become not just the small person everyone in town knew. He was a true celebrity,” said Kean. “The match didn’t disappoint. Jimmy’s victory may have been predetermined, but his throng of supporters went wild when he pinned his opponent in the ring. Even if he had not gone farther with wrestling, I think that moment cemented a special place for Jimmy Buckle in the hearts and minds of everyone in Corner Brook.”

But Jimmy Buckle did go farther, much farther.

GROWING UP

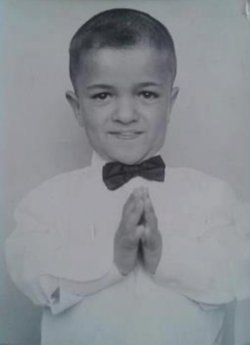

He was born in Corner Brook on September 26, 1960, to a family of eight children, six girls and two boys, the fifth born. His father worked in a pulp and paper mill and his mother kept the home running.

Jimmy wasn’t just the only small person in his family; growing up, as far as he knew he was the only little person in the entire province.

“My understanding is that I was the only little person on the whole island at the time,” Buckle said. Though he was a midget wrestler, he is a dwarf.

Growing up, there were many challenges to being four-foot-four.

“It was very hard, as far as I’m concerned, but I grew up in a time where we didn’t complain about it,” he said. “We didn’t bitch about everything like today.”

A young Jimmy Buckle.

An example: The sleeves on anything they’d buy would be 8-10 inches longer than his arm. That meant rolling up the sleeves, but with something like a winter coat, it would “feel like you’ve got a great, big donut right there around your elbow.”

An added complication were his feet, small but extra wide. That forced him to seek out bigger shoes than necessary. “It was almost like walking in snowshoes for regular shoes,” Buckle described.

“Mom and Dad didn’t raise me to be somebody to be small, little and pitied,” he stressed. “I was running all over the city before I was five years old.”

His diminutive size offered opportunities, and his uniqueness helped him stand out.

“I got to do a lot of things as a kid that a lot of kids would not do,” he said, recalling heading out for deliveries with truck drivers or riding along with the garbage trucks.

Therefore, he learned how to be around adults and became a good conversationalist. “They liked my companionship and in the meantime, I got to learn a lot of knowledge that I would not learn in school.”

As he got older, Jimmy learned how to make a few bucks too.

“When Jimmy was a young boy, he was known to head downtown with a box and shoe shine supplies to make some cash shining up the shoes and boots of anyone who would let him,” recalled Kean. “Being quite athletic, Jimmy was also known to entertain people by doing flips for coins.” There were traditional teenage jobs too, like mowing lawns.

The circus came calling, having heard about his acrobatic skills and wanted him to leave town at 10 years old, offering him $350 a week, but his parents wouldn’t let him go.

His notoriety never left. “I was a community mascot. I’ve been on live stage. I’ve been a referee in hockey games, mod-hockey, like one radio station against another radio station.”

A young group of wrestlers includes Jimmy Buckle, bottom row, second from left.

WRESTLING

In high school, he took to amateur wrestling, learning the skills under Brother Squires. He ended up with a silver medal in the All-Newfoundland competitions in the 95-pound category.

“His powerful athletic skills were a big asset he used to his full advantage,” said Kean. “He was a star on the varsity wrestling team, taking down boys much taller than him regularly.”

It was one of Jimmy’s sisters that had pushed him into the pro wrestling game.

“George Cannon was doing TV out of Montreal. My older sister wrote a letter to him, telling him that I’d be interested in midget wrestling,” he said. “Sometime later, I got a reply from him that he’d be interested in talking to me this coming summer, because he was coming down to do a tour.”

So when Cannon brought his Superstars of Wrestling promotion on a tour of Newfoundland, Buckle went out to see the show. That was June 1979.

Farmer Pete, of Hamilton, Ontario, was only a year older than Jimmy Buckle, but had already been wrestling a couple of years, primarily for Cannon and other promoters around Ontario.

“I used to do the Newfoundland tour with George Cannon and we ran into him at the shows,” recalled Farmer Pete (Paul Richard). “He was interested. He started off coming into the ring with me, like a second. We actually talked to his mother down there and she was okay with it, so George sent him to Littlebrook.”

In the 1970s, Lord Littlebrook was the major promoter of midget wrestling. He’d been a star wrestler in the 1950s and 1960s, after coming out of the circus in England. Settling in St. Joseph, Missouri, Littlebrook began training wrestlers, both big — Butch Reed is certainly a big name — and small.

Buckle didn’t find the training all that difficult.

“For me, it wasn’t too bad because I was in good shape overall. My biggest challenge was the transition from amateur wrestling to pro wrestling,” he said. His acrobatic abilities complicated things. “My natural instinct, instead of landing on my back, was to always land on my feet. I had a little bit of trouble at the beginning taking some of the bumps, because you’re supposed to land on your back and not on your feet. Naturally, I was wanting to land on my feet.”

Being a teenager so far from home was an adjustment. As was the weather.

“If anything, what I had to put up with the heat exchange. You come from Newfoundland, where 50 or 60 degrees is summer, and at that time, when I came down here in ’79, is when they had that damn heat wave, 102-105 for like 40 days. It cooked my ass! I was in shape, and even though I was in shape, I was panting like a dog.”

The training lasted just a little over a month.

ON THE ROAD

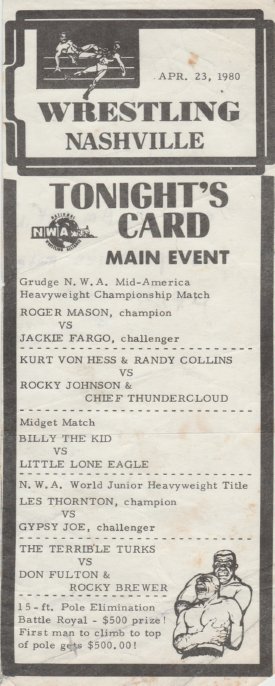

A card from Nashville in 1980.

Booked through Littlebrook, Chief Lone Eagle hit the road, beginning with Cannon’s tour of Newfoundland. From there, it becomes a bit of a blur, as the midgets were generally special features in territories, meaning that they’d be in an area, like Stampede Wrestling, for a couple of weeks at most, and then on to the next territory. Travel was constant.

“Really, we didn’t stay anywhere long enough to know these places. We were in and we were out,” he said. “I do wish we’d gotten paid a little more, a little better. Most of the time, guys go into a territory and are there for nine months to five years. We go into a territory, we’re only in there for a week or two, and we’ve got to pay hotel prices, where they pay apartment prices.”

Ten percent of their pay went to Littlebrook’s booking fee. “Littlebrook didn’t have to worry about paying for a hotel when he was getting his 10%, or his food, or his trans.”

For most of the 1970s and into the mid-’80s, if you wanted to book a midget wrestler on your show, you generally had to go through Littlebrook. That meant that there were times where the midgets knew they were making more money than the local wrestlers, like in Tennessee, for the notoriously-cheap Nick Gulas. “It’s the power of Littlebrook having the little guys, and if you want them back again,” said Buckle.

Chief Lone Eagle knew he had a role to play.

“The little people were there to make the people laugh,” he said. “The more that we can make them laugh and enjoy it, the more the promoter likes us and would want us to come back again. Sometimes, they would even ask for the same fellas where Littlebrook would say, ‘No, no, no, let me send you a couple of different guys.'”

Working with other midgets or dwarfs, like Little Tokyo, Cowboy Lang, Farmer John, Tiny Tom and Ivan the Terrible, Buckle found a fraternity. They didn’t always get along, but they did share similar issues and had to work together.

“If you don’t have your partner, you don’t work,” said Buckle. “For little fellas, this is one way we can stay in shape, because we can’t go to Gold’s Gym and work out, like everybody else can, because none of that stuff is made for us. So we’re in the ring wrestling with each other, even though we’re doing a competitive thing, we’re also conditioning each other as a co-partner or spotter.”

A brotherhood and sisterhood of little people exists, and they know similar issues and obstacles — like using the bottom of the door on the fridge rather than the handle.

Midgets and dwarfs are a true minority, he pointed out. “There’s fewer midgets than people with autism or any other diseases,” Buckle said. “My thinking is, us little people, us midgets, we’re more the minority than any of them, because we’re few and far between.”

The word “midget” has been deemed politically incorrect in recent years. Buckle can understand why, but isn’t militant over the word. “I’ve got nothing against it, as long as it’s not used in a bad way. It is what it is. It’s part of life,” he said. “If you’re going to be sarcastic about it, then yeah, I don’t like it.”

Chief Lone Eagle all dressed up.

The midget wrestlers felt the bumps the same way their bigger compatriots did, and Buckle found a way to cope.

“I really didn’t get into the drugs. The only thing I was ever into, and I was into that before I even got into wrestling, and that was smoking a little reefer. That’s how I did day to day,” he said.

Buckle is a believer in the medicinal benefits of marijuana.

“It also helps me with the stresses of my dwarfism, because every time I sit at the kitchen table, my legs are hanging down, or if I’m on the toilet, or if I’m doing this, or I’m doing that. Not a damn thing is made for me and once in while it just gets under your skin,” he said. “I look at it like it helps my nerves. It’s kind of a weird logic. Little people are supposed to be normal, but we’re not normal, because we’ve still got our minds, but our body is screwed up — but we’re still supposed to be the same thing as if we’re six-footers.”

SETTLING DOWN

On the road less than a year, Buckle met a young woman named Sonya Boyd, and was smitten. She was a little person too, but under completely different circumstances. Sonya (and her sisters) had rickets, a disease of the skeletal system as a result of a deficiency of calcium salts, Vitamin D or sunlight. Born April 22, 1960 in Kentucky’s Warren County, she spent the first 21 years of her life as regular at Kosair Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She topped out at four-foot-one in height.

“Basically, I chased one woman, which was my dream girl. I ended up marrying her. I married until she died,” said Buckle. They married in 1983, which changed the wrestling career for Chief Lone Eagle. Instead of constant travel, he took wrestling bookings here and there.

“I stayed rasslin’ for another year, and with me being on the road, and her being at home, wasn’t a good family life, so I got out of the business and got a family job,” he said. “The next thing you know, I started doing it for the next 20 years as a weekend warrior.”

A family portrait: Sonya, Jimmy Sr. and Jimmy Jr.

His day job was working in a factory making gaskets.

“I called my wrestling on the weekend my Wal-Mart money,” he joked. He had a title belt made — he did briefly hold the Midget World title, beating Little Tokyo in Houston. “I guess it was more of a gimmick thing because all the big guys have got to have one, so we’ve got to have one for the little guys too,” he said. “I really didn’t care for it, because it’s weighing around another 25 pounds in your bag.”

Sonya and Jimmy raised one son, Jimmy Jr., who was born in January 1986 and grew to four-foot-one. When their son was old enough, Sonya went to work as a teachers assistant with the Logan County Board of Education.

It was freeing being away from Littlebrook and dealing directly with the promoters, said Buckle. “I was the total boss. I set the prices. I did it all.”

From his Kentucky home, he could jet off to New Orleans or Chicago by plane, maybe a couple of shows in Florida the next weekend.

“I used to get off of work at 3:30. I could be in Nashville by 4:30-5 o’clock,” he recalled. “I’m not going to jump into the ring for five, ten dollars!”

Sundays were a day off, the way he believes it should be.

Jimmy Buckle shows off his motorcycle.

A HIGHER CALLING

Having gone through so many challenges in their lives, Jimmy and Sonya made a point to give back to their community. In particular, they were big supporters of the Special Olympics, and helped out at camps for the developmentally disabled.

Buckle’s current church is the First Presbyterian Church in Russellville, Kentucky.

Pastor Tom Thompson speaks very highly of Buckle.

“Jimmy has been an active member of our church for a couple of years now. Throughout his life he has come to understand that he has a very special ministry,” said Pastor Thompson. At times Jimmy can be a teacher, preacher, philosopher, friend, parent, counselor, and child of God. Although many people might look at Jimmy’s size and think of it as a disadvantage he certainly doesn’t. I have often asked him to write a book about his life and put in a special chapter on how his size has affected not only his life but most definitely how it affected others as well. He planted a lot of seeds for others which said ‘with faith, and perseverance one can achieve.'”

Annie Hall lives just outside Russellville, and also attends the First Presbyterian Church. She praised Buckle’s willingness to help others. Her husband is a disabled Vietnam veteran and her mother, suffering from Alzheimer’s, recently moved into their home. Overcome with tasks, Hall was at her wit’s end.

Buckle was there to help.

“I could not have been able to get the things that I needed to get done around here without him. He showed up one day with his lawnmower. He continued to help me mow grass all summer,” recalled Hall. “He volunteered to come over and help my family build us some decks. After that day, my siblings and I adopted him as our ‘little bro.’ We have not been the only people in our community that have enjoyed his help and company. He has shoveled ice and snow, every day, for a family at our church that were experiencing the last days of their dad’s life. He kept the drive and walk cleaned so the medical help and family could get in. He drove my son, at the drop of a hat to pick up his truck that broke down in Virginia. That trip was several hundreds of miles. He has been known to drive by someone’s place and see something that needs to be done. He will stop and do it. This man sure knows how to show God’s love.”

Religion was a balm when Sonya fell ill, and died January 14, 2011.

“My wife was sick all her life. I stayed with her until the end,” he said. “A lot of men would not do that, especially in the States, because that’s just another damn bill.” They persevered through two miscarriages and were warned after Jimmy Jr. was born not to have any more children.

Sonya and Jimmy.

Five years after his wife’s passing, Buckle has high hopes of finding a new companion. “It’s not like there’s little people in every country,” he sighed. He recently traveled up to Maryland to meet a fellow little person.

KEEPING BUSY

There always seems to be something to keep Buckle busy.

There are meals to be delivered to the less fortunate, bingo numbers to be called at the senior centre, and he loves to tinker with his motorcycle.

Jimmy Jr. become a welder, but ran into trouble with the law a few years back for using crystal meth, and this may will mark two years in prison. It’s complicated, admitted his father. “I’m fighting myself if I want him back home or not,” he said.

Jimmy Jr. and Jimmy Sr.

Wrestling is definitely in the past, though Buckle loves the memories. He’s had three back surgeries.

“I would love to do it, but being on disability, they wouldn’t understand that 15 minutes [in the ring] is not the same thing as eight hours,” said Buckle.

He still marvels at some of the experiences.

“You’ve got to think now, it was nothing for us to do 100,000 on our ass every year. It would be nothing to go from Florida to Missouri, turn around a week later and go to Portland, Oregon,” he said. The midgets had their own car (four cents a mile for transportation charges), with the pedals raised up higher, and cushion behind and under them in the front seat to allow them to drive. Buckle carried a portable pedal extension with him to allow him to drive non-modified cars.

Jimmy Buckle has never forgotten his roots in Newfoundland and Labrador either. He makes a point to head home every few years to see family, including a 2010 Christmas surprise to his mother, Jean — it seemed everyone in Corner Brook knew he was heading home but her.

At nearby Fort Campbell, Kentucky, Buckle has befriended soldiers, and in 2012, convinced the powers that be there to fly the flag of Newfoundland and Labrador as a tribute to the military plane crash in Gander, NL, on December 12, 1985. The crash killed 248 American soldiers — based in Fort Campbell — and eight crew members.

“He may have eventually faded from the memories of some, but you ask almost anyone in Corner Brook of a certain vintage if they know who Jimmy Buckle is and a smile will immediately form.” said Kean. “Jimmy has never forgotten where he came from either.”

“I’m always a Newfie and will always be a Newfie. They’re not going to take that out of me,” laughed Buckle.

“Many people from Corner Brook have left and gone on to do great things. Jimmy Buckle certainly stands tall among them. He is seen as someone who has never considered the fact he was short as being an obstacle to living life to the fullest. He is also known as someone with a big heart that he wears on his sleeve,” concluded Kean. “I, like many others, see Jimmy as an inspiration for perseverance and as a great ambassador of his hometown and province.”