Willie “The Wolfman” Farkus barked for the last time today, squeezing the hand of his son Mark, as he left this world, off to see his many, many friends from the world of professional wrestling, and his beloved wife, Ethel. He was 80.

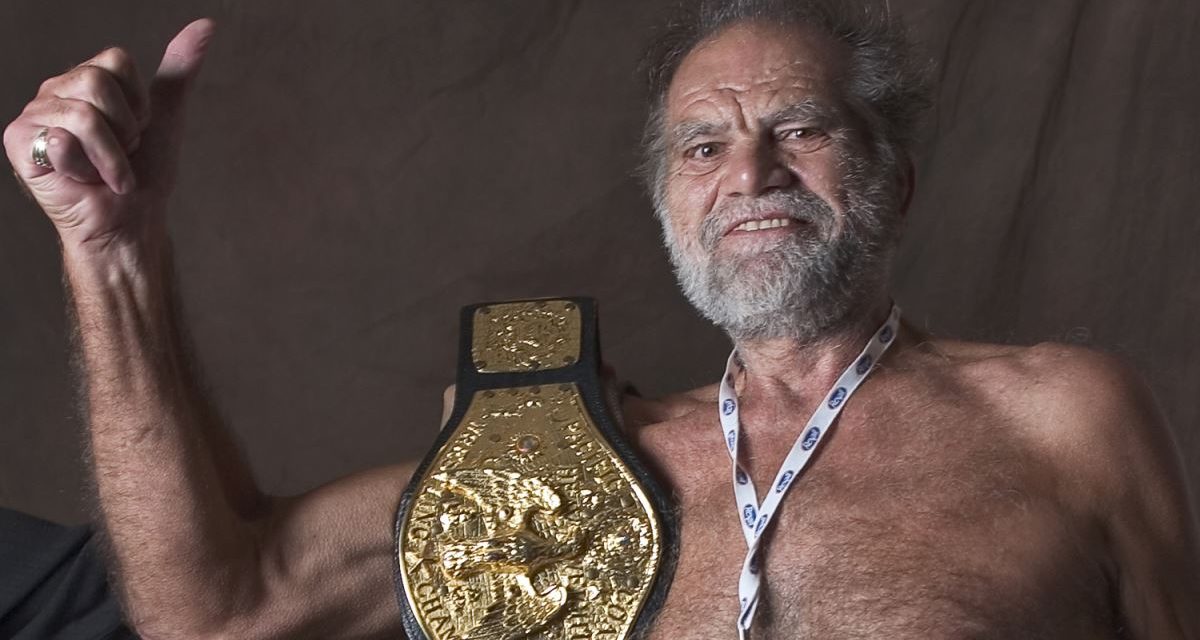

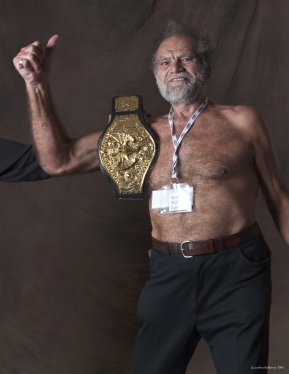

Willie The Wolfman Farkus, acting as only he could, at the Titans in Toronto dinner in 2008. Photo by Andrea Kellaway

He had battled many health issues over the last number of years, and was released from a Toronto hospital in mid-December, heading home to his apartment, appropriately right next to Maple Leaf Gardens. He knew he was heading home for his last days.

To know him was to love him, said “Rotten” Reggie Love.

“Everybody loved the guy,” said Love. “I’ve known him for so long I know exactly what he’s saying, even though nobody else does.”

Through his thick Hungarian accent, “Wolf” or “Wolfie” often struggled to make himself understood, which offered up its own unique charm.

His best run came in the WWWF in the 1970s, managed by Classy Freddie Blassie, when he challenged for the World title held by Bruno Sammartino.

The champ thought so much of the Wolfman that when Sammartino was up in Toronto a few years back, he requested that both Wolfman and Sweet Daddy Siki come out to see him at the WrestleReunion fan fest.

The Hungarian Wolfman was led to the ring by a chain, clad in animal skins, with an unkempt beard and wild hair. Sometimes billed “from the wilds of Canada,” Farkus would gnaw on his opponents in the ring, often forcing the wrestling shows to censor his lunacy — he said it was Gorilla Monsoon who suggested he bite the of heads off chickens on TV. Promoters sometimes even said he had been raised by wolves.

The wolf head and skin that he got from a Toronto taxidermist and that he wore to the ring could be an issue, laughed “Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe, who remembers a call to a WWWF taping when Farkus was delayed at the Canada-U.S. border. “He got stopped because Customs wouldn’t let him bring that fur through because they thought it had some kind of disease on it.”

Farkus’ backstory as an immigrant to Canada is as unique as he was.

In 1956, Vilmos Farkus fled Hungary for Canada to escape the Communist regime. He settled in Ontario initially, where an uncle lived, picking and packing tobacco.

It was suggested that he head out to Calgary, where he worked in a factory, hired because he was a big, strong man; English skills didn’t matter.

While in a bar having a few beers, Farkus got into a fight and was arrested. He spent a year and a half in jail on a three-year sentence. He used the time to work himself into top shape.

Upon his release, he met Calgary wrestling promoter Stu Hart who suggested he consider training for the sport. He did briefly, but then, on a whim, a family he knew was packing up everything and moving to Toronto, and he went too.

In Toronto, he met Mike Scicluna — later known as Baron Mikel Scicluna, and started training with him in a local gym. According to Farkus, Scicluna beat him up pretty bad the first day, but he came back the next to earn his teacher’s respect. “Mike is a tough son of a gun,” said Farkus. “He kick you, you feel it. He’s a tough, tough guy.” Other young men training at the time included Dave McKigney and Wally Seiber, who would become Waldo Von Erich.

Pro wrestling was made for a personality like Farkus, who just loved to be around people, to travel, to hang out, to walk around town and draw attention, his tender heart not always aligned with his villainous ways.

“Always love it, years ago, always love it,” he said of professional wrestling.

Again, another story on the love others had for Farkus.

Beverly Shade and her husband Billy Blue River came up to Ontario one summer to work for Bearman Dave McKigney. For two weeks straight, Blue River worked with the Wolfman.

“He just loved him to death,” recalled Shade. “Billy just loved Willie. Everybody thought Willie was crazy, but Billy just loved him to death.”

It’s with the Bearman that the Wolfman is most associated, which makes sense given that they were best friends as well as tag team partners.

When McKigney was killed in while on a tour of Newfoundland and Labrador in 1988, along with Pat Kelly and Adrian Adonis, Farkus stopped wrestling. He was on that tour — “my best friend died. I no wrestling. I go there for Dave, help Dave.”

The Wolfman was the one charged with bringing McKigney’s young son, Davey, back to Ontario.

Farkus kept a photo of the wrecked van that belonged to the Kelly twins in his wallet, a reminder.

Through the years, Farkus was a fitness fanatic, and until a heart attack in 2011, was a familiar sight around Toronto streets, just walking and walking.

He used to go faster, said wrestler Big Mac (Mervyn McKie). “He used to wake me up at 5 a.m. every morning. ‘Mac, go jogging,'” said Big Mac. “I used to have to translate for him in restaurants.”

While the Wolfman is most associated with Ontario and the Bearman, he worked plenty of other places, including Los Angeles for Mike LeBell and in Texas. He often brought his family — wife Ethel and his stepchildren Mark and Joanne — with them. Mark later wrestled a bit and refereed for McKigney.

Tiger Jeet Singh used Farkus on some shows, including tours of Trinidad.

“He’s a character of his own,” said Singh, launching into a story:

“He got caught at the airport. They wanted to deport him. His wife called me, ‘Oh, they caught my husband, Tiger. Help him.’ I said, ‘Why did they catch him?’ He was lying. He told them he was coming as a tourist, but the skin he used to wear was in his suitcase. His wife, she was so nervous. I made one call from here and all the Indian people are at the Customs. So I told them who he is, that I was coming to promote, and they need to help him. They said, ‘Okay, if you’re coming, we’ll take him out.'”

Singh later learned that the ID that Farkus had with him at Customs in Trinidad was a YMCA card.

Farkus talked to the Mississauga News for a story in 1999, and discussed his wrestling days.

“We weren’t paid much at all, hardly anything really,” Farkus said. “Some of the arenas were very small and the spectators few. We were paid as little as $25 a night.

While the money not have been much, the memories — for Farkus and for the fans — were priceless.

The family expects there to be a small, private ceremony in the coming days.

Greg Oliver will miss Willie, and knows he is not alone. Rest in peace, my friend. Your pain is over.

RELATED LINK

Mat Matters: Saying goodbye — in two languages — to the Wolfman