John Gacek and his fellow soldiers didn’t have time to observe Armistice Day. They were too busy putting their lives on the line.

On Nov. 12, 1944, a day after the 26th anniversary of the armistice that ended World War II, Gacek was fighting along the Lower Rhine River in Holland, where Allied soldiers rotated on a 24-hour basis to bring relief to battered, hollowed-out towns.

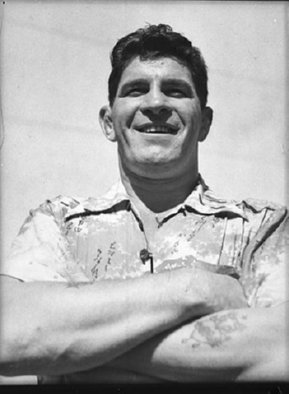

Jack Gacek in 1938. Photo by Sam Hood

Under cover of darkness, members of a U.S. Army 401st Glider Infantry company moved over narrow canals to defend their positions. They’d fought through D-Day five months before and now were engaged in an epic 72-day fight that became the basis for a famous movie.

At one of the canals outside of Opheusden, a German patrol was waiting.

“A sharp firefight ensued and three Company A men lay dead including Staff Sergeant John Gacek, the pro wrestler. All of the Germans were killed, but one of the 401st’s heroes was, too,” Robert Bowen, who served in the battle, wrote in Fighting with the Screaming Eagles.

At 33, Gacek, became pro wrestling’s first fatality in World War II. He died a day after he was shot, leaving behind two children, fans around the world, and unfinished career on the mat.

“The rugged outdoor life he lived enabled him to build up one of the most beautiful steel-like, Herculean bodies seen in any ring,” the Rib Lake Herald editorialized when he signed up for a bout in his hometown in 1940.

“This has enabled him today to be one of the most gifted, determined and recognized contenders for the World’s Championship and the idol of the wrestling world, for he has the thing that all sports fans are interested in, that is — the way he can take it as well as hand it out.”

Gacek was born June 9, 1911, in Minneapolis as one of nine children to Benedick and Tekla Gacek. The family moved a few years later to rural Rib Lake in the north-central part of Wisconsin, where Gacek toiled on the family farm and helped out his father, who was a carpenter.

By 16, he was heavily into amateur wrestling and was billed as light-heavyweight champion of the state, though that might not have been a formal title. Promotional materials claimed Gacek played football for three years at the University of Detroit, but that was probably just publicist’s hype — enlistment records credit him with a year of high school and he doesn’t turn up in university football records.

Regardless, Gacek was a good athlete who went 5-foot-9 and 208 pounds. He started his career close to home in the fall of 1933, working several matches against Johnny Paulin in Milwaukee. By the middle of 1934, records show that he was often wrestling at least once a week and holding his own against the likes of Rudy Kay, Kid Ewert, and Paulin.

He also was an integral part of one of wrestling’s great innovations. On a cold February 1935 night in Milwaukee, Wis., Gacek lined up with fellow Milwaukee grapplers Kid Ewert and Andy Rockne against a trio of wrestlers from Chicago — Pete Holtz, Johnny Forman, and Kay.

The occasion was the first team match in wrestling annals and the forerunner of tag team matches that have been a staple of the sport for 80 years. Each pinfall counted as one point and a wrestler had to leave ringside if he lost two falls, the earliest known example of Survivor Series rules. In the final fall, Gacek wrestled Holtz to a draw, leaving both sides unsatisfied with the outcome but with a secure spot in wrestling history.

After the novel team match, Gacek broadened his horizons, working in Chicago and New York through the latter part of 1935 and 1936 against Oki Shikina, Tony Colesano, and John Swenski. He’d work as a good guy and a bad guy; in December 1936, he did a stellar job of riling up fans in Manitowoc, Wis. “A woman fan offered to do battle with him if he would step down out of the ring and a young mob scene was staged after some especially rough tactics. But the fans seem to like that sort of going,” the Manitowoc Sun Messenger reported.

In March 1937, he moved to Northern California and was billed as “Touchdown” John Gacek. His biggest win to that point was probably an August 1937 match in Fresno, Calif., against Japanese star Kaimon Kudo. He also beat Ted “King Kong” Cox by disqualification, a common outcome for the rule-breaking Cox.

Gacek’s showing was enough to earn him a trip across the Pacific in 1938, where he appeared in Hawaii, Australia and New Zealand. Using the octopus as his finisher, Gacek returned to California for the balance of his career, occasionally working as “Dr. Zack Gacek,” losing a few more than he won against tough guys Bill Longson, Rudy LaDitzi, and Cox. But the Oakland Tribune hailed him for using “scientific methods” to knock off one-time coast champ Lou Plummer and the Nevada State Journal singled him out as “one of the finest men in the game today.”

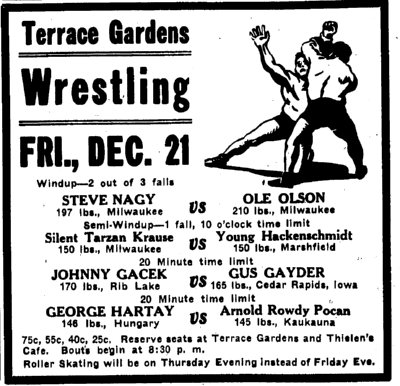

A clipping from the Manitowoc Herald Times, December 20, 1934.

Gacek’s final recorded match was July 1941 in Atlanta; he was touring the Deep South states where promoter Gus Kallio identified him as “the peppery Polish matman.” Military records show that he enlisted Oct. 13, 1942. But he kept his tights on, wrestling in the service and maintaining an open challenge to Army sparring partners.

In fact, in the months before D-Day, Gacek and a handful of GIs were training in England when they put on matches to crown a European Theater wrestling champion and keep the troops entertained. During one set-to at an air base, Gacek beat Bob Kawka, who wrestled professionally as Bobby Roberts in the 1930s, with his vaunted octopus lock.

“There is fear here among prospective opponents for Gacek that he might forget how to untie himself from his newly conceived ‘hold,’ and since it hasn’t been recorded, some might suffers,” military newspaper Stars and Stripes said tongue-in-cheek.

Matters became more serious in a hurry. As part of the 327th Glider Infantry, Gacek and his co-fighters were dropped into combat behind enemy lines on military gliders, as opposed to parachutes. The glider assaults were less than ideal; broken arms and legs often resulted from crash landings.

The 327th was involved in the Utah Beach D-Day landing in June 1944. Near Auville-sur-le-Vey, Gacek was one of two men who ran through the countryside, strafing it with bullets so they could break through German fire. In Holland, the regiment hooked up with the 401st in Operation Market Garden amid ferocious fighting captured in the 1977 movie, A Bridge Too Far. Just a month before Gacek died, two men in the 327th were killed when they were caught up in a fusillade of 2,000 artillery shells.

Gacek’s death didn’t attract much attention notice in the nation’s sports pages. After all, he was just one of nearly 160 members of the 327th alone who died in action or suffered fatal wounds, according to military records. He is buried at Lakeview Cemetery in Rib Lake, a wrestler who made the ultimate sacrifice for his country 71 years ago this week.

REMEMBRANCE DAY / VETERANS DAY STORIES