During his hockey career in the WHA and NHL, Cam Connor racked up 1,160 penalty minutes, using his fists to settle many on-ice issues. But it was a fight in a Winnipeg garage as a teen that came to mind this week. His opponent? Rod Toombs, better known to the rest of the world as Roddy Piper.

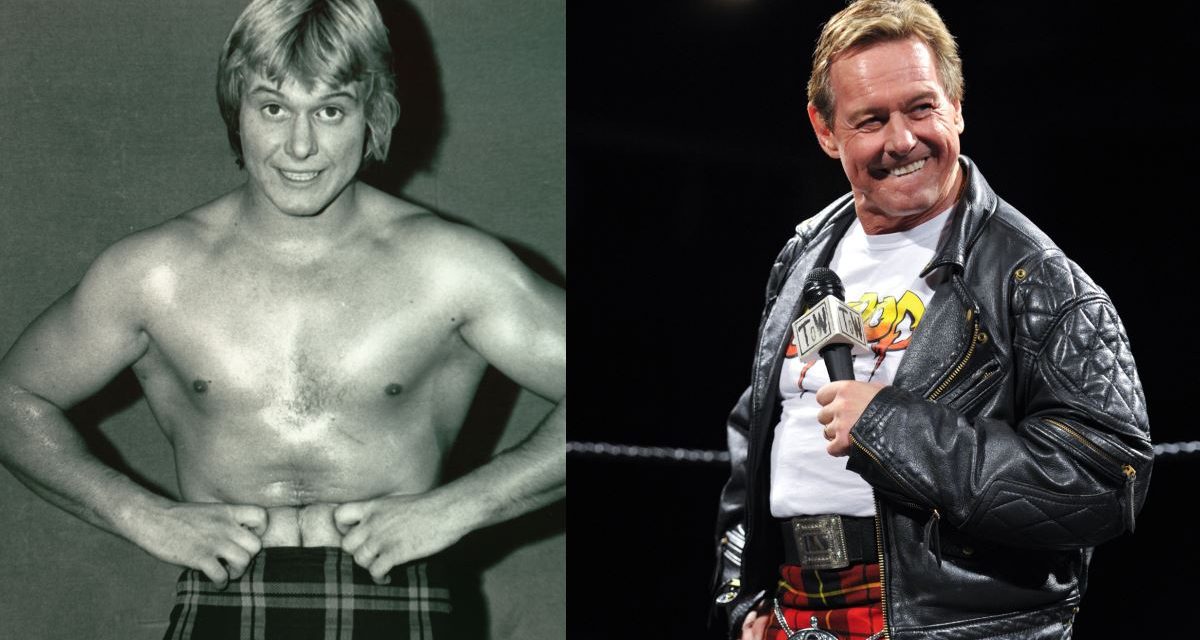

Roddy Piper and Cam Connor. Photo courtesy Cam Connor

Piper, who died on Thursday night, was a nomad growing up, as his father worked for the CN railroad as a policeman, but his teenage years were spent in Winnipeg.

When he moved to town, from Toronto, he ended up in the same high school as Cam Connor.

“When he moved in, some mutual friends actually brought him over to my house,” said Connor on Saturday. It was a tough neighborhood, and the teenagers, in Grade 10, were destined to meet.

“Basically, it sounds a little crazy, but the guy said, ‘Cam, you’re a tough guy, and this new guy, Rod, he’s a tough guy. Why don’t you have a fight?’ Simple as that. I said, ‘Okay.’ We went into my garage, and Rod and I went at it, and I did not know he was a boxer out of Toronto, so he beat me. Then we had mutual respect and from that day forward, we’ve hung around together and stayed in touch for over 40 years.”

In fact, Connor and Toombs talked on Wednesday night. “He called me. I live in Edmonton and he phoned me, I was in Calgary, so he phoned my cell. We had a great conversation. I said to him, ‘Let me call you Friday.’ Little did I know Wednesday night would be the last time I would talk to him.”

Connor said his buddy knew always what he wanted to be.

“We hung around, and Rod always knew that he wanted to be a wrestler. He wrestled in high school. I was a very strong kid, he was a very strong kid, so we’d always wrestle, at his house, at my house, in the yard. He could box, so we would put the gloves on, and we would box.”

Windsor Park Collegiate had a weight room and Connor and Toombs took full advantage.

“After school, Rod and I would go down and work on the weights, just the two of us; nobody else was ever in there,” Connor recalled.

They challenged each other, he said.

“I never knew I was going to be a pro hockey player. I just wanted to be better than average. So did Rod. So we both realized that we had to work harder than other people. We didn’t have natural talent, but we had desire and hard work. So we would push the weights, and when I was ready to quit, Rod wasn’t, and he would tell me, ‘Keep going, do a couple more sets.’ I said, ‘Sure.’ I pushed myself with Rod’s guidance. Every day, after we finished the weights, I would throw up because I had no more to give. That was Rod’s doing.”

With the different requirements of their respective sports, they grew differently — Connor was about 10 pounds heavier, though they were both close to 6-foot-2. Connor’s legs bulked from the skating, while Piper was more even.

“As time went on, I think Rod was a little man in a big man’s sport, so he bulked up, maybe to as high as 250, 260 at one point,” said Connor, who worked in computer consulting after his hockey career petered out in the mid-’80s; now he works in the camp catering business for the oil, mining and forestry industries.

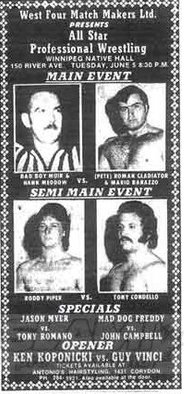

Connor was there for the real debut of Roddy Piper.

“I was with Rod his very, very first fight. We knew he was going to be the bad guy. He had no money. He had to wear his boxing shoes in the wrestling ring. We said, ‘How do you stand out?’ So we went and picked a bunch of dandelions and he had this basket, as he was walking to the ring, he’d pull out handfuls of dandelions, and he’d throw them at the spectators all the way up.”

Through his buddy, Connor got to know some of the key figures on the Winnipeg wrestling scene like Al Tomko and Tony Condello. “We’d go have beer together after some local matches in Winnipeg, and outside of Winnipeg.”

Piper rarely talked about those early days on the wrestling scene in Manitoba, though, often claiming that his first match was in the old Winnipeg Arena against Larry “The Ax” Hennig. Connor understood why Piper played it down. “It would be like me talking about a lower level in hockey. That’s almost like playing in the minors when you talk about those early days for Rod.”

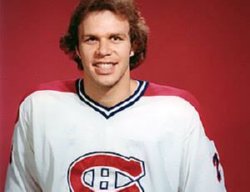

Cam Connor with the Montreal Canadiens. |

Connor was well-traveled as far as hockey goes, with a couple of seasons each with the WHA’s Phoenix Roadrunners and Houston Aeros, and then the NHL, with the Montreal Canadiens — where he was on the 1979 Stanley Cup winning team, and scored the double-overtime winner to win Game 3 in Montreal’s quarterfinal playoff series Toronto Maple Leafs in 1979 — the Edmonton Oilers, and four final seasons with the New York Rangers.

With the WWF based in Connecticut, and New York City’s Madison Square Garden getting regular WWF shows, Connor got to see Piper fairly often.

“When Rod would come in, he’d stay at my house, or stay in a hotel. My wife also knows him, I dated my wife since we were 15 — so Rod and I and her all went to the same school, so she knows him very well. Rod would give us tickets and we’d go watch his matches, quite a few of his matches. We’d wait for him after. These guys, they fight seven nights a week in seven different cities, so we’d spend a little time after and then he had to get on a plane or drive to the next city.”

A show with Roddy Piper in Winnipeg in June 1973. |

The WWF schedule of the time was insane, with as many as nine or ten shows in a week, especially for an in-demand headliner like Piper. That meant lots of health issues, said Connor.

“I just know what he went through to be successful, and he paid an awful price. These guys in wrestling, they fight seven nights a week in seven different cities. They don’t have an off-season. If they don’t fight, they don’t play. I was with Cowboy Bob Orton, and I hadn’t seen him for two years. I said, ‘You’ve still got that cast on the arm. Is that a prop?’ He said, ‘You know what? If I don’t fight, I don’t feed my family.’ That arm never healed. He had to keep getting re-set and re-set and re-set. When I got hurt in hockey, we got to mend, we got to heal, and we got a paycheque coming in. These guys didn’t, so they had to fight night after night after night after night. And hurt. I would never do it. I’d have to help him off the couch 20 years, he couldn’t even get up, his back was so screwed up, hips were all screwed up. I would never do what he did, ever.”

The talk shifted to concussions, and how the Piper he saw a couple of months ago in Edmonton — Hot Rod was in town with a writer, starting to work on a proper autobiography and wanted to collect memories from Connor, who took two days off work to hang around — was not the Rod Toombs he remembered as a youth.

“Knowing Rod’s lifestyle, the things that he shared with me, they get banged up. I would guesstimate — I’ve had four to six concussions, that when I played, you didn’t have to wear helmets, you could hit from behind, we’d get punches in the head, we’d get pucks in the head, we got sticks over the head. I would guesstimate, with Rod being a little man in a big man’s sport, and you see the piledriving, you see into the turnbuckles, you see a foot to the head, I bet you, over his career, he had a hundred concussions.”

Therefore, Connor was asked to fill in the blanks of Piper’s memory.

“They brought this writer because Rod doesn’t remember a lot of the stories out of Winnipeg, out of us growing up, us in New York. He said, ‘I’m not very smart.’ I told him, if he knew Rod in the early days, his mind worked brilliantly. He may not have been able to talk about school and that kind of smarts, but his mind, Rod’s brain worked. But I told Rod, ‘Rod, please don’t ever say that about yourself. I’ve know you your whole life, and all these concussions, it affects your memories.’ He has post-traumatic stress disorder, he had a lot of things that contributed to that, 100 per cent.”

Before the conversation ended, Connor wanted to tell one more story about his friend.

“I liked Rod because it didn’t matter if you were the CEO or you held the door open for him, he was always polite, and he treated everybody with respect. I saw that for 40 years. I remember, in Winnipeg, the main street downtown is called Portage Avenue. Rod didn’t have a good home life and he didn’t live at home very often. He only had $30 to his name. We didn’t have a lot of panhandlers when we were growing up, on the main streets, but there was a guy sitting there with his cup out. Rod and I walked past him, and I knew Rod only had $30 in his pocket — that had to last him for a week and a half, and he had hotel room bills and food he had to buy. He turned around, and I watched him, he went back and he pulled $20 out of the $30 that he had in his pocket, and he put it in this old man’s tin cup. What impressed me the most is he came back and to this day, he’s never, ever bragged what he did. You see people that do something for somebody else and then they tell the world, ‘Well, look what I just did.’ He did it from the heart. We all have our flaws, Rod had his flaws. For myself, if I’m to judge somebody, I look at that core, how you treat other people, how honest are you, how sincere are you. I have these values. Rod, he had that core. He’s consistent. He could have any of the flaws outside and I could put up with him forever, because he had that core — and I saw it time and time again, how sincere he was. He was a big brother when he was a teenager. If there was some other child that was less fortunate, he would go take him out and entertain the guy, take him to the zoo. Rod, he was a very, very sincere person. He gave more than he took from this world for sure.”

RELATED LINKS