By STEVE JOHNSON & GREG OLIVER – SlamWrestling

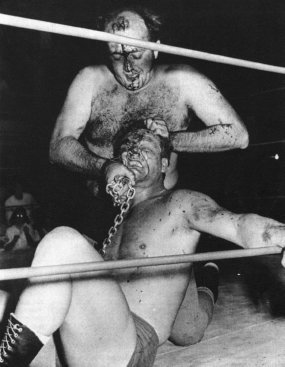

There aren’t too many photos of Ron Wright without blood. And the legendary Tennessee heel, who died today, didn’t hit a gusher in his forehead with the nick of a razor blade, but rather in a far more violent fashion, with a much bigger weapon.

“We used to have those Brass Knuckles fights down here,” recalled Rick Connors, a Ron Wright trainee. “We’d bleed profusely. I mean, I ain’t talking about razor blades. We had those filed-down knucks, it’s like a pair of brass knuckles — I’ve got one pair left here — with a giant blade, about one inch blade, it’s about an eighth of an inch high, and it would go plum to the skull. We really believed in authenticity back in those days. If you’d seen some of those matches down here, around Tennessee, back in those days, when you left, you knew it was real. Plus we did hardway, guys got black eyes, bloody noses. It was real.”

Ron Wright is bleeding, naturally. Photo courtesy the David Williamson Collection

As they say, there’s wrestling and then there’s rasslin’. And out in the hills and hollows of eastern Tennessee and Kentucky, nobody practiced rasslin’ quite like Ron Wright in the 1960s and 1970s. Even though he did not spend much time on the national stage, folks who worked with him say Wright’s brawling tactics and motor mouth earned him as much acclaim in his backyard as any world champ could hope for. “Ron Wright is, was, and will always be the king of the east Tennessee hillbillies,” said Scott Spangler, a.k.a. Brian Matthews, former announcer for Smoky Mountain Wrestling, in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. “People in east Tennessee loved to hate Ron Wright.”

You won’t get much argument from Wright. “I was pretty hated and I guess I still am,” he said upon his induction into the Knoxville, Tenn., Wrestling Hall of Fame. “Looking back, it probably is deserved. I was pretty raunchy.”

And bloody.

Dr. Tom Prichard will second the thoughts of Rick Connors: “[Ron Wright] is the quintessential, classic, stereotypical east Tennessee redneck rebel, flag waving, old whomp-your-ass rassler. That is him. In the olden days they had this thing that they called the chisel and they used to sharpen it up like brass knucks, and they’d sharpen it like blade where it’d come to a sharp point and they’d get the guys juiced that way.”

Every great heel needs a believable, sympathetic babyface, and for Ron Wright, and his “brother” Don Wright, it was Whitey Caldwell. The Wrights were the Hatfields to Caldwell’s McCoy, and their rivalry stayed fresh for years on the strength of ever-more-imaginative booking. In November 1962, Caldwell came from behind to win the final four falls in a shave-your-head match against Ron. A few years later, the Wrights resorted to a chloroform-laden rag during a televised match to knock out Caldwell and take the Tennessee tag title from him and Les Thatcher. In July 1970, when Ron relied on a loaded boot to kick his opponents into unconsciousness, Caldwell wore a crash helmet into the ring, and then clobbered Wright with it for the winning fall. Tornado matches, chain matches, strap matches with 10-foot-long-leather bindings … you name it, and they did it, and the ensuing carnage was enough to propel the small territory to the cover of national wrestling magazines.

Ron Wright said Caldwell had a short fuse that he knew exactly how to light it, so their matches became even more believable. “The first match we ever had, I broke his shoulder. I didn’t mean to. It was an accident. I threw him over the ropes and he came down wrong. Every time I talked about that, that’d set him off.” Wright said. “He didn’t like it when I badmouthed him. That made me do it even more. So when he got in the ring, he was already mad.”

In an interview with the KayfabeMemories.com website by Steve Webber and Ron Gott, Wright talked more about Caldwell: “I drew so much money with him. There was very few matches I got in the ring with Whitey that there wasn’t blood, I’d say 95 percent of our matches I had with him or that anybody else had with him. He was so self-conscious about being little that he’d just beat you to death. That’s just the way Whitey was. That’s why when you got in the ring with him it was a fight and you knew it, and that’s why you’d draw money with him. If I was ever at the mall or something and saw Whitey I’d go into a store or something to avoid meeting him because he’d run over and knock your head off instead of ignore you and walk on by, that was the temper that Whitey had over the matches.”

In his hometown of Kingsport, Tenn., in the early 1950s, Luther Ronald Wright began wrestling as a teenager at a Boys Club. After a few years, he decided to step up his level of competition by squaring off with pros that passed through the area. “I kept challenging them, they kept rubbing my nose in the mat stretching me out pretty bad, I kept on and on I wouldn’t quit,” he explained to writer Gary Langevin in 1995. “Then a bunch of them kind of took a liking to me.” Wright played some football in high school, but wrestling killed his amateur status. Though he turned in a couple of years with a semi-pro football team in Baltimore, he achieved more infamy as a bad guy. He held the Southeastern title three times, the Tennessee brass knuckles title twice, and did work some in the Carolinas and Florida, as well. For most of his career, he had a day job at a pressman in Kingsport, while his night job consisted of inciting riots.

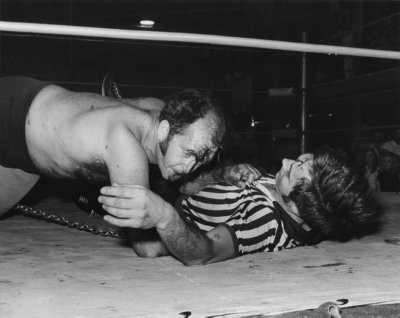

A bloody Ron Wright crawls onto the referee.

Upon learning of Wright’s passing, at age 76, on April 21st, just days after entering hospice care, wrestler/trainer/broadcaster Les Thatcher called him “one of the greatest heels I ever worked with and an East Tennessee legend.”

Wright did not disappear after his in-ring days were done following a car accident in the mid-1980s. He trained a few select wrestlers, like Connors. “Me and a friend of mine drove to Kingsport twice a week, and we worked out in a barn, an old tobacco barn. You’d take a body slam and dust would fly to the ceiling. It was a good way to break in, though.”

As well, Ron Wright acted as a manager for both the Fullers and then Jim Cornette‘s Smoky Mountain Wrestling. His gimmick was a foreshadowing of sorts; he managed from a wheelchair, claiming that he had a heart problem — and then in April 2011, he did have a pacemaker installed.

While his body couldn’t perform, Wright never lost his gift of gab, said Spangler. “Listening to Ron rant and rave, I began to notice that Ron’s speech patterns were reminding me the way an old-fashioned Pentecostal tent revival preacher would preach,” Spangler said. “Even at his age then, ol’ Ron Wright still had the people in the palm of his hand.” When fans started getting restless during a feud between “Dirty White Boy” Tony Anthony and Tracy Smothers over the burning of a Confederate flag, Wright, sitting ringside, didn’t flinch a bit. “He just looked at me and winked and tapped the top of the blanket.” After the show, Spangler asked Wright what he meant by the tap. “In that east Tennessee drawl of his, he said, ‘Them ol’ boys don’t know who they were a-messin’ with. I had my ol’ 9-millemeter under that blanket.’ ”

Ron Wright at ringside at a show in 2011.

Cornette got lots of extra publicity by trucking out the likes of Wright for legends nights, and on his Twitter feed today, he paid tribute. “Ron Wright was a household name & a cultural icon to three generations of East Tennesseans, and boy could he talk,” wrote Cornette. “One of the greatest promos, hottest heels and toughest men ever in our sport, Ron Wright, passed away this AM. RIP to the King of Kingsport!”

In his final match, Wright, with a hip and shoulder replacement, came out of retirement to pin Anthony as part of a dream matchup show in Johnson City, Tenn. That day — August 12, 1995 — was Ron Wright Day in Kingsport. “Talking about a territorial heel, he was just fantastic,” said “Nature Boy” Buddy Landel. “People outside of Tennessee and around there are not going to know him. But the wrestlers that sprouted out of there, such as myself and Tim Horner and guys from that region, we owe everything that we are to people like Ron because we stood on his shoulders for years.”