By now, it’s been done to death in pro wrestling, but you can look it up. Ken Ramey was the first turncoat referee.

It happened in Florida, in the territorial days of the mid-1960s, when the masked Medics tag team of Billy Garrett and Jim Starr went scouting for a third member. They liked Ramey’s work as one of the top referees in the National Wrestling Alliance and suggested he talk to Florida promoter Eddie Graham about ditching his striped shirt.

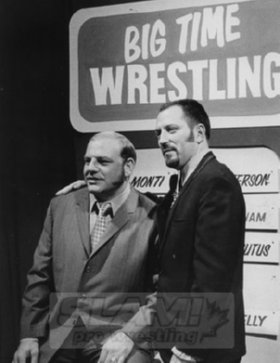

Paul DeMarco and Ken Ramey in San Francisco.

“I could make more managing than I could as a referee,” Ramey recalled. Graham hesitated until Ramey suggested he could go on TV and explain that the match reports he filed with the NWA as a ref provided him with the clues he needed to take The Medics to the top.

“Everybody who comes down here, we can beat. I guaranteed these boys if I become their manager, I will guarantee them that I will make them world champions,” he told TV announcer Gordon Solie. Soon enough, police had to escort Ramey and The Medics up and down the 36th Street Causeway in Miami Beach to prevent fans from tearing them apart, limb by limb.

That was just one example of the resourcefulness that Ramey demonstrated during three decades as a referee, manager and booker. He died in his sleep after a battle with cancer on October 16, 2014, in Bossier City, La., where he lived with wife LaJuana. He was 83.

As a kid, Ramey lived in Chattanooga, Tenn., and hung around the YMCA with the brother of Eddie Gossett — the given name of Florida promoter Eddie Graham, for whom Ramey would work. “It didn’t dawn on me till later who Eddie was,” he said.

Ramey was exposed to wrestling in California when he was working audio for what was the fledgling ABC network, attending a few matches with buddies and meeting a few wrestlers, though he didn’t consider himself a fan.

When he relocated to Atlanta a few years later, he ran into Wild Red Berry, whom he’d met in California. He ended up hauling the ring for promoter Paul Jones after a worker no-showed, and a career was born.

“It just progressively got from there. I started refereeing a few times around Atlanta, then went to Houston where I refereed, then came back to Atlanta and started to referee around Atlanta a lot,” Ramey said.

He got to be close friends with Ray Gunkel when Gunkel took charge of the Georgia promotion. In Mobile, Ala., he started promoting a few shows and did well, and also traveled to Memphis to work for Buddy Fuller. Back in Atlanta, he became the booker and a full-time office employee.

Ramey was about ready to drop out of wrestling, though, when he visited Amarillo, Texas, and stayed on at the request of Dory Funk Sr. He referred, promoter Hereford, Texas, and wrote the program for Amarillo.

“Most territories, if you went into the office and made a complaint or something, you got your two-week notice. If you were a good hand and everything, you went in with Funk and you voiced your opinion, the next day it was over with,” Ramey said.

“If you said something in the Florida territory around Graham, you were out of the territory and when you left you didn’t have any good bookings. That was it. He’d starve you,” he said.

Ken Ramey at ringside. Courtesy Chris Swisher

As a ref, Ramey is considered the originator of the pantomimed one-two-three count, where he physically showed the crowd that the count got only to two.

“Lou Thesz used to love it. He was a little slow in the ring and everything, so it helped him,” Ramey said.

It also helped him to show that he, not he wrestlers, was in charge inside the squared circle.

“One time Jose Lothario, I counted one, two, he didn’t raise his shoulder up, three. All of a sudden he jumped up and realized what happened. That wasn’t the finish. That wasn’t the finish. I had to count it. It was right out in front of everybody. He was working with Johnny Valentine. Valentine said, ‘He didn’t raise his shoulder up. Don’t put the blame on Ramey.'”

Vincent J. McMahon, owner of the then WWWWF, tried to get Ramey to referee in his federation after seeing him in the ring at a match in the old Capital Arena in Washington, D.C. But New York only used referees approved by the state athletic commission, and Ramey never pursued the matter. “They wanted me,” he said of McMahon’s group. “I went up there; I referred and they said, ‘Hey, wait a minute, here’s a guy that knows how to referee.’ But there was a big problem” in getting commission approval, he said.

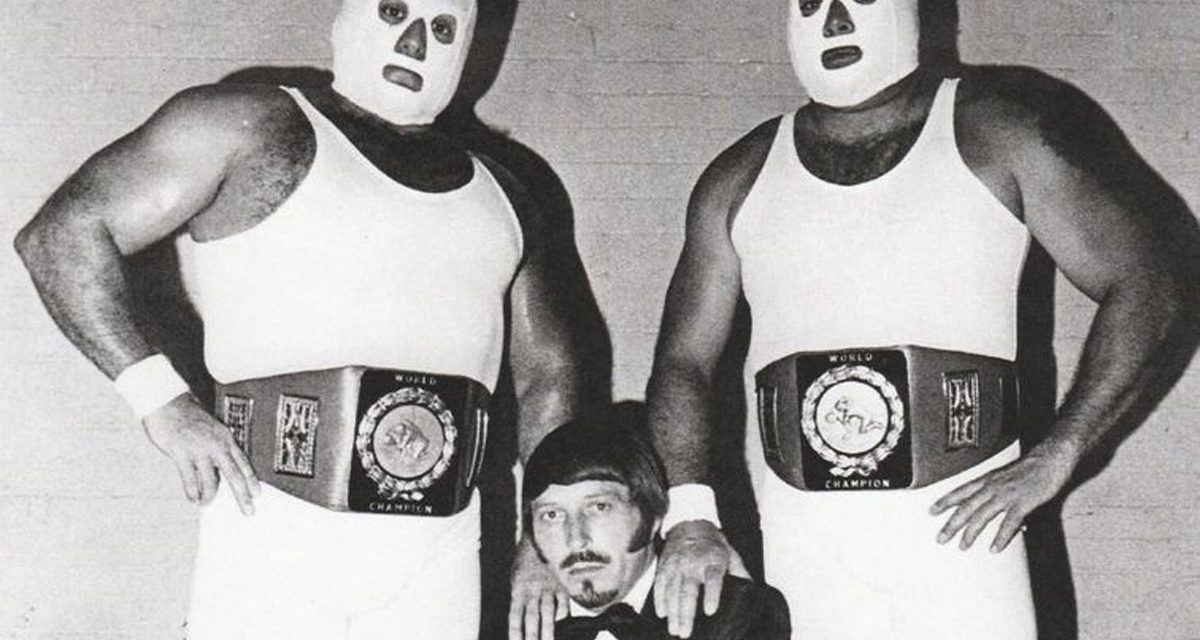

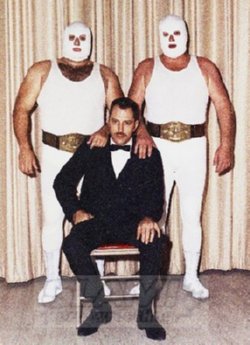

Ken Ramey and The Interns. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Ramey managed The Medics, also known as The Interns as Tom Andrews replaced Garrett, for about a decade. In Birmingham, Ala., they developed one of the most controversial angles in history, knocking out black star Bearcat Brown with a gimmicked chloroform cloth, then painting him white.

“Ramey announced Bearcat Brown was so scared of The Interns that he turned white and fainted. That tape that we did with Bearcat Brown and Len Rossi, we capitalized on that for about a year-and-a-half,” Andrews said.

“We had the sheriff’s department, the provost marshal’s for the guys in the service, and the city police all come down there.”

Ramey also managed The Interns in San Francisco, as well as Pat Patterson, Buddy Rose and Paul DeMarco, who was the northern California’s territory’s U.S. champion several times. Dave Meltzer of the Wrestling Observer called him “one of the most underrated managers of all-time.”

Ramey had a very clear idea of his role as manager — keep it all in the ring and never engage the ringside fans.

“I talked with Billy [Garrett] about it, that we’d never do any finishes outside the ring. Because if you do it outside the ring, only the people on that side of the ring get to see what you’re doing. Everything we did, we did it in the ring,” he said.

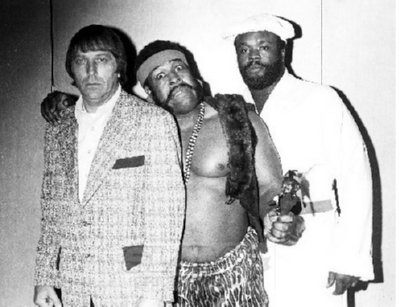

Ken Ramey with Leroy Rochester and Ormund Malumba. Courtesy Chris Swisher

“I would never argue with the people. If you get one old lady or one old man out there and they start arguing with you, people around them are going to start laughing ’cause it’s cute, it’s funny, and it’s a comical thing. Well, you do that and people in the audience all of sudden they take their eye off the ring to see what in the world is going on with the manager. Then you’re defeating the purpose of what you want to in the ring.”

DeMarco was the only singles wrestler that Ramey spent much time with. “He was a great worker. He would do, I thought, some silly things at the wrong time in the ring, take a crazy bump or something when he should have still been getting heat. I used to talk to him about it. But when I was with him, DeMarco was a great guy,” Ramey said.

A search for his DeMarco in the communes of northern California as the San Francisco territory started to close down in 1978-79, led to one of Ramey’s favourite tales.

“So I got in my car and found it, went up that trail in my car and I got to the point where I said, ‘Man, I’m stuck up here, I don’t know whether I can go any further or not.’ Surely, there’s got to be something, so finally I went up in there, it must have been a mile, a mile-and-a-half or something, I come up on a clearing and there was a couple, three houses up there. … And I went over there and he was living with a woman. But DeMarco wasn’t there. And DeMarco, she told me DeMarco’s gone up the stream or the river winding up there, and they live off the natural grains and stuff.

“Then about two or three weeks later, we’re at TV one day, and who shows up? Paul DeMarco! He came down to see me,” Ramey laughed. “He and I had a long talk and everything. He had gone back to nature.”

Pepper Martin and Ken Ramey with their awards at the 2006 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion.

Ramey regularly attended Cauliflower Alley Club reunions in Las Vegas. He was presented with an award in 2006 and the club’s annual bowling tournament is named in his honour.

RELATED LINK