There was no reason for Ken Ramey to be in Amarillo, Texas in 1967, other than the fact that it represented a convenient way station on his road to oblivion. Ramey enjoyed some success refereeing and working in wrestling offices in Georgia and elsewhere, but he was getting into his mid-30s, and he felt he wasn’t getting anywhere, what with the restlessness and personal trials that accompany life.

So he packed up his necessities, and headed from Georgia to California, where he figured he could hop on a freighter bound for Australia or New Zealand. “Someplace down there, anyway,” he recently told SLAM! Wrestling. “I was going to jump off of it, and stay down there for the rest of my life. The hell with all this crap.”

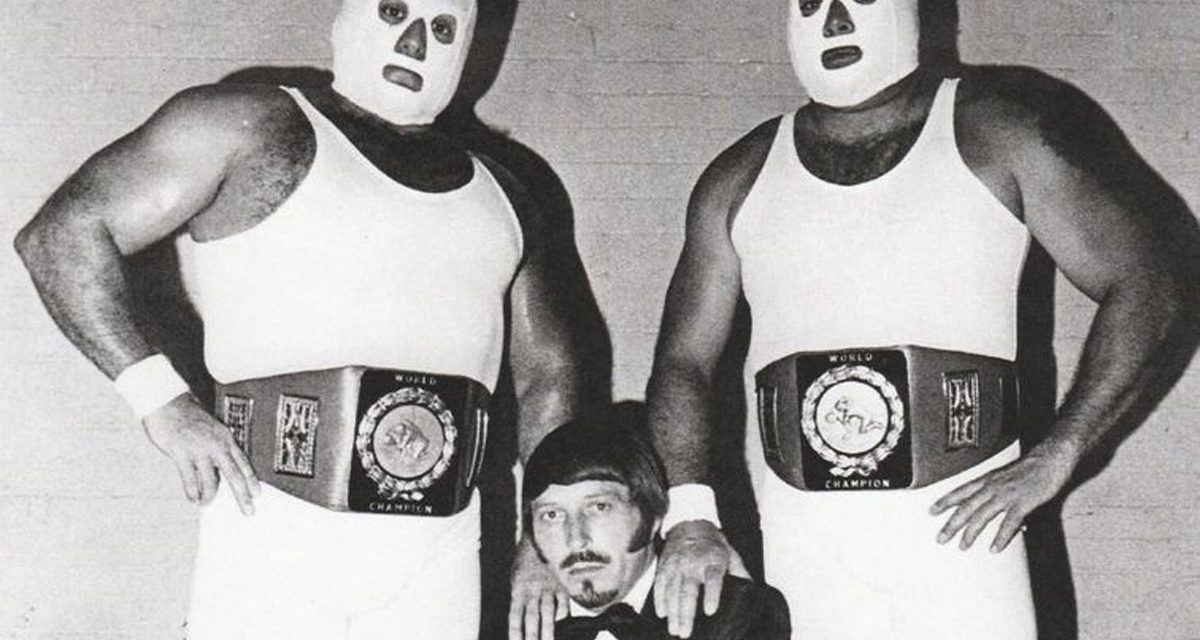

Dr. Ken Ramey

But when Ramey dropped in on some matches and a Saturday television taping on his way through Amarillo, he found that promoter Dory Funk Sr. had rebooked his itinerary.

“Funk said to me, ‘Look, we don’t have no referee for TV. I need you for TV,'” Ramey recalled. “I said, ‘No, I’m fixing to leave.’ I had everything, pants, shirts, my underwear, some socks, and my wrestling gear, and that was it. I was getting out of the way.”

Funk was nothing if not persistent. He offered Ramey $50 to work the taping, up from the normal $25. He also said he’d send him to Littlefield, Texas to referee matches for $75 that night. What’s more, when Ramey later dropped by Funk’s ranch to deliver the gate receipts from Littlefield, he was greeted with a steak dinner.

And John K. Ramey suddenly saw the tramp steamer leaving port without him.

“He talked me into it. He wasn’t going to let me out. I said, ‘I’m leaving.’ He said, ‘No, you’re not. You’re staying here.’ When Funk put his hands on you and said you wasn’t going, you wasn’t going. Anyway, I said, ‘All right.'”

For the next 15 years, few figures in wrestling were as clever, innovative, and professional as the man whom Funk declared would not be an expatriate. In June, Ramey will be honored by the Cauliflower Alley Club for his work as a highly regarded referee and one of the most despised managers of all time.

Ramey was set for a career in radio and electronics when he stumbled into wrestling. In 1939, at the age of nine, he was the youngest person to hold a first class amateur radio phone and key license. That served him well when he went to California in the 1950s to work for the American Broadcasting Company.

Something else caught his eye in the Golden State, though — pro wrestling. Ramey attended a few matches at Legion Stadium in Hollywood. When he went east to Atlanta in about 1955, he attended more matches, renewed an acquaintance with famed manager “Wild” Red Berry, and became a go-to guy for wrestlers who needed television and radio repairs.

It wasn’t long before Ramey became a go-to guy in the wrestling business, as well. Within a few weeks, Georgia promoter Paul Jones asked him to haul a wrestling ring to a spot show. “Whoever it was who supposed to take the ring up didn’t show up. He wanted to know if I’d take the ring up there and put the ring up. I think he told me it paid $25 or $30. Well, back in the fifties, $25 or $30 wasn’t that bad,” Ramey said.

From there, he progressed into a role as the third man in the ring in Georgia, Houston, and Memphis, and expanded his reach into promoting shows around Mobile, Alabama and booking the Georgia territory, before deciding to quit the business, renew his radio license and subsist somewhere in the outback.

“I fell in love with Funk,” Ramey said. “He told me he’d pay me good money, a little better than preliminary money. He gave me Hereford [Texas] to promote, so I got the profits out of Hereford, and wrote the weekly program for Amarillo. Hey, that was the first time I really made any big money. He paid you fair. You got a good payoff from what was in the house, better than most territories.”

If a wrestler griped to a local office about conditions or payoffs, Ramey explained, a pink slip usually was on the way. But Funk, though sometimes hot-tempered, was tolerant with his troop. “If you were a good hand and everything, you went in with Funk and you voiced your opinion, the next day it was over with,” he said. When Funk died unexpectedly of a heart attack in June 1973, Ramey broke down and cried. “I loved the man that much.”

By then, Funk witnessed Ramey’s rise to the feature pages of national wrestling magazines. In 1968, Ramey served an unproductive stint for The Sheik in the Detroit area. “I absolutely starved to death up there. Couldn’t find any place to live, the whole time I was up there. My wife and kids were staying in a hotel in Toledo.” But Florida office executive Buddy Fuller rescued him by bringing him south and even chipping in $200 for moving expenses.

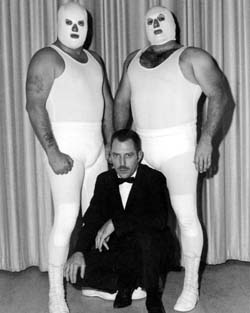

Ramey and the Interns.

As a referee, Ramey was one of the tops in the game, regularly earning assignments to National Wrestling Alliance championship matches. With the help of the original Gorgeous George, he refined his style and was one of the first to physically demonstrate a count of two to the audience.

“Gorgeous George told me one time, ‘You’re a good referee; you need to learn your trade and try to get better.’ I came up with idea. One, two, and then I’d come down, all of a sudden, I’d almost hit the mat and stop, and raise up — only two! I’d take my shoulder and pantomime that even if he was a little late getting it up, I was covering up for him.”

Ramey’s next innovation made his career. Billy Garrett and Jim Starr, working as The Medics, urged Ramey to consider becoming their manager. Eddie Graham, who ran Florida with an iron fist, balked at the notion, but allowed Ramey to propose a potential storyline. Ramey’s booking days in Georgia proved to be handy, as he created the notion of a turncoat ref.

“I got on TV with [announcer] Gordon Solie and I brought a bunch of books and said, ‘You know, I’ve been a referee and we keep records of all the matches and everything. After every match, I write down who won and who lost, and how it was done and so forth, and I write it up and send it to the NWA. These gentlemen have made me an offer I cannot refuse. With these records that I’ve got and the information that I’ve got, I guarantee you we can beat everybody in this territory,'” Ramey remembered. “That tape showed around one week and I couldn’t make it to the ring.”

The Medics turned Florida on its ear, winning every available title and packing houses in the process. After irate fans smashed Starr’s car, The Medics and Ramey — now a “doctor” to fit the team’s profile — received a weekly police escort to the Miami Beach Auditorium. “We had the world’s tag team, Southern tag team, Florida tag team, the TV tag team and Tampa City cup. We had about five belts. And we had so much heat you could not believe it.”

The Medics also hit it big in Oklahoma and California, and, when Tom Andrews replaced Garrett in 1971, the pairing, known as The Interns, started a run in Tennessee and other states that elevated them to a spot among the greatest teams of all time. Particularly memorable was a TV taping in Birmingham, Ala., where The Interns laid out African-American star Bearcat Brown, while Ramey threw whitewash on him. Cackled Ramey: “Bearcat Brown is so scared of The Interns, he turned white!” After calming fans and local police authorities, the territory drew money from the angle for years.

Ramey was very exacting in the way he managed, avoiding ringside confrontations like the plague and maintaining a focus on the match. “My theory on the managing part of it was I never would carry anything to the ring with me and I never would argue with the people. I thought that was the silliest thing.”

That, he noted, was a preferred tactic of manager Saul Weingeroff, but Ramey said it hurt the business. “If you get one old lady or one old man out there and they start arguing with you, people around them are going to start laughing ’cause it’s cute, it’s funny, and it’s a comical thing. Well, you do that and people in the audience, they take their eye off the ring to see what in the world is going on with the manager. Then you’re defeating the purpose of what you want to do in the ring.”

As to the referee’s work, Ramey, as a former official, had strong views on keeping fan ire on the wrestlers and not the referee. “We used to tell the referees, ‘If you see it, break it and we’ll go back and do it again. Don’t pretend you didn’t see something when everyone in the building knows you did. We don’t want heat on the referee.'”

Ramey never had a big stable of wrestlers, preferring not spread his heat too thin — in fact, he left Florida when Graham wanted him to manage several wrestlers a night. “There were some guys down there that I didn’t trust. I’m not going to get out there and get a riot started or something, and look around and I’m by myself … for the same dadgum money.” He later hooked up with Flash and Rocket Monroe in the Gulf Coast area, helped Paul DeMarco headline in San Francisco, and also worked there with Buddy Rose.

But no matter who he was managing, he always had a few tricks up his sleeve, such as the magically appearing paper. “Instead of me getting up and running up and down to distract the referee, I’d take a wad of paper and toss it up in the ring. Then I’d jump up and say, ‘Hey, referee, here, here. Get the paper out of the ring.’ … In the meantime, my guy is doing something,” he said.

After couple of repeat performances, Ramey would point high into the audience to indicate that troublemakers were continuing to litter the ring. “The referee would go over and say, ‘Tell the people if they don’t stop throwing stuff in the ring, I’m going to stop the match.’

“It got to the point where in Las Vegas one time, the sheriff’s department came down and told me, ‘If you throw one more piece of paper in the ring, we’re taking you down and gonna lock you up for inciting a riot, ’cause that’s exactly what’s fixing to happen.'” I said, ‘OK,’ but I wasn’t planning on throwing any more or that was all I had. So it worked out perfect that night.”

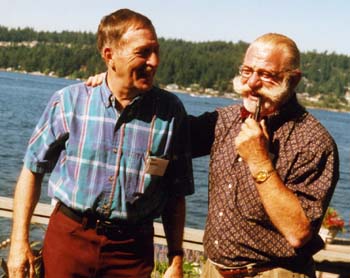

Ramey, left, and Red Bastien at a get-together in recent years.

For all of his fights, Ramey, 75, defeated his toughest opponent earlier this year, when he completed treatment for cancer that had spread to his neck and throat. He lost more than 40 pounds during chemotherapy treatments and will be on thyroid pills for the rest of his life. But he is grateful to the physicians at Houston’s renowned M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, and the good Lord, for helping him make a full recovery.

Even his bowling game is rounding back into form. An avid bowler with a lofty 200 average, Ramey was so weak that he was rolling the ball down the lane with two hands. “There was women rolling the ball harder and faster down the lanes than I was. So, shoot, when I started back, there was nights when I didn’t even have a 400 series. I’d still be in the 300s. In the middle of those 300s, I bowled games of 85, 87, 103, 110, something like that.

“But now, I’m starting to get me some 180 and 190 games back again. Every day, three or four people come up. ‘How you feeling? You’re looking better. I notice you starting to bowl the ball better.’ It’s really nice.”