When John Foti took his own life on April 29, 1969, in Calgary, he was a 41-year-old shell of the man that he used to be. Early in his career, Foti was a top-of-the-card worker, earning draws with the likes of Whipper Billy Watson, Johnny Valentine and even Lou Thesz, and taking on top names such as Killer Kowalski.

By the end of his days in Stampede Wrestling, he was an unreliable fill-in.

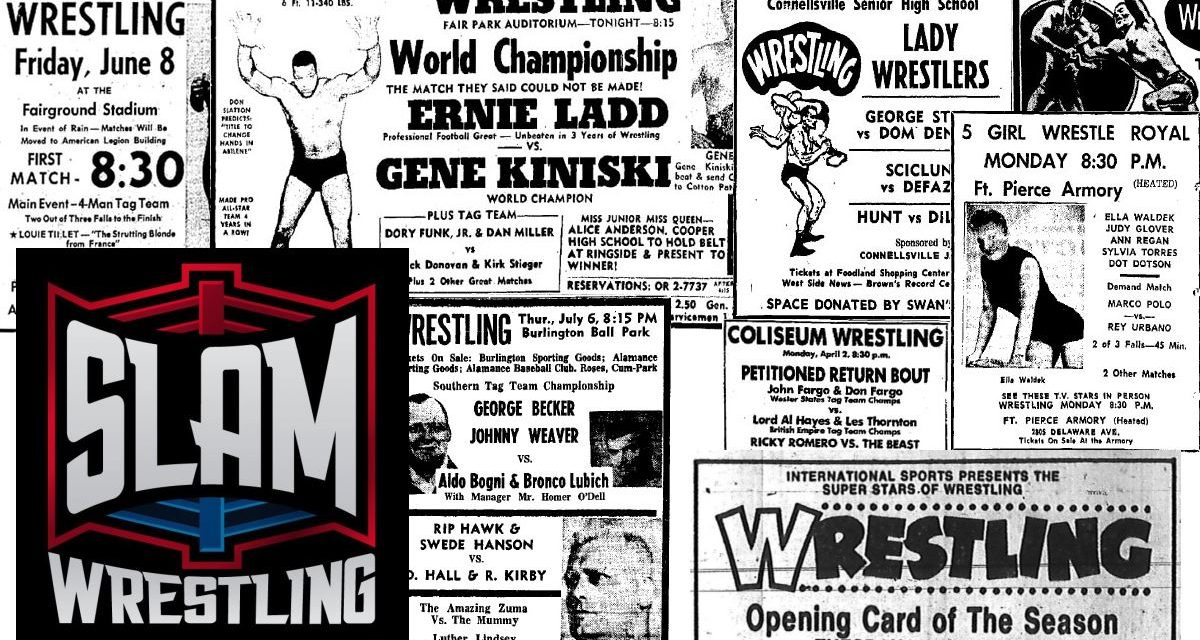

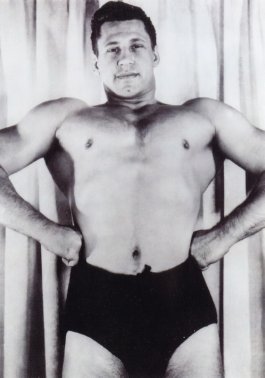

John Foti

“John did himself in. He was an alcoholic, a raving alcoholic. He couldn’t help himself. At the end, you couldn’t rely on him much,” said another Stampede regular, Gil Hayes. “I stayed late in town, waiting for him, to pick him up so I could take him into Edmonton. We just about missed it, and [promoter] Stu [Hart] was on my case about. I said to Stu, ‘If you want me to be a babysitter for somebody, you’re going to have to pay me extra. And by the way, I don’t need any aggravation from you; he’s your responsibility, not mine.'”

The story of Foti’s 15-year wrestling career begins in Hamilton, Ontario, where his mother ran a restaurant, and where there was probably something in the water that helped produce countless pro wrestlers from “The Factory.” Though born John Fotie on March 13 1928 in Regina, Saskatchewan, where his father was from, as a teen he headed east to Hamilton to escape his father, with whom he had a strained relationship. To strengthen himself, Foti started working out at local gym, where he worked out with the likes of George and Sandy Scott, Billy Red Lyons and Skull Murphy.

By the mid-1950s, he was on the wrestling circuit, usually in upstate New York or in Ontario, often billed as being from Buffalo.

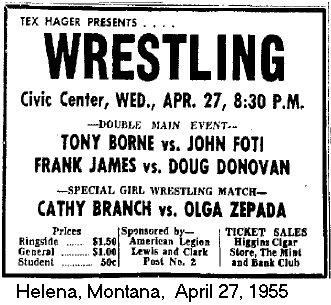

In April 1955, he was out in Montana, where the Helena Independent Record newspaper promoted “John Foti, Newest Ring Darling, Here Wednesday,” describing him: “Foti, a 215-pounder, is a clean, scientific wrestler with a wide variety of legal holds.”

Later that year, he was working for Hart in Stampede, and a September 10, 1955 program described Foti:

John Foti, 230-pound heavyweight from Regina, is the typical kind of young man who has to leave home to make good.

Although he first got interested in wrestling in the Saskatchewan capital, Foti couldn’t get a start in pro ranks there so went to the United States to get into the game.

He broke in around the state of New York, caught the eye of some old timers, was given a chance to learn the finer points of the game in New York City itself, developed into a colorful performer who has been much in demand in the eastern states.

He has now returned to western Canada and there is one thought uppermost in his mind. He wants to show the home folks, particularly in Regina, that they passed up a good bet when they didn’t give him a chance to wrestle in Saskatchewan in the first place.

Like many wrestlers, the hometown Foti was billed under switched through the years, based on where he was working. In Stampede, he was always true to his Regina roots, and would stay with family when the crew swung through town. When working out of Winnipeg and Minnesota around 1957, he was billed from Hamilton. Circa 1964, he worked as an undercard guy in the WWWF, and was decribed in one story as a “clever Canadian.” It was likely in the WWWF that he befriended Tony Marino, who would call on Foti to dress as Robin to his Batman, in an in-ring Caped Crusaders duo designed to capitalize on the popular Batman TV show.

“John’s a good one,” said Edmonton frontman Rocky Wagner in 1962 in a program, “and he could be the guy who puts Kowalski in his place.”

Hayes worked with Foti numerous times, and recalled his style. “Wrestling was a natural to him. He wasn’t one for working any highspots. You were working holds, and working off of holds. You spent a lot of time on your back … you’re not going to be doing a lot of criss-crosses or backdrops or anything like that.”

Jerry and Bobby Christy also competed with Foti in Stampede. “He was a good worker, [but] he was a fantastic artist,” remembered Bobby Christy, adding that Foti gifted him with a painting of a ship, since lost in a fire.

Jay Fotie, one of four Fotie offspring, with two sisters and a brother, admitted that he didn’t see his father a lot growing up, with him so often on the road.

“I really didn’t know much about my dad’s wrestling when he was alive. After he died, I started going to the wrestling a little bit. What I know about the wrestling is basically what I saw,” said Jay Fotie.

“His biggest asset was that he was a really good artist. I’ve still got some of his paintings,” said Jay, noting that he generally painted with oil, mostly scenic images. “My father’s true passion was oil painting, mostly landscapes and nature. While he enjoyed the competitiveness and limelight of professional wrestling, he craved the solace and tranquility that only a canvas and paint brush could provide. The wrestling paid the bills and gained him a level of notoriety but his art was his true calling.”

Examples of John Foti’s artwork, courtesy Jay Fotie.

Journalist turned referee Merv Unger wrote a story about Foti for the Calgary Herald in June 1967.

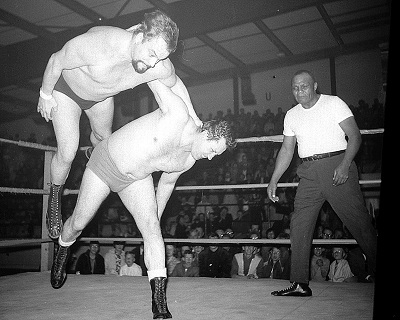

“I spent a lot of time with John while we lived in Calgary. He was a very troubled man at the time, living in small motels or apartments with his wife and four kids,” recalled Unger. “He and Stan Stasiak ran one of the greatest blood feuds in Stampede Wrestling history, selling out for weeks and weeks. I refereed some of those matches. They are among the most memorable of the hundreds and hundred of matches I was involved in.”

John Foti battles Stan Stasiak, with the special referee Jersey Joe Walcott watching. Photo by Bob Leonard.

Unger’s article talks about Foti’s love of painting, which started in elementary school. Encouraged, he enrolled at the University of Saskatchewan summer arts school at Murray Point on Emma Lake at age 13.

While struggling as a young man to establish a career — he worked in Hamilton factories and on the docks — Foti put his painting aside. When he found himself with so much time to kill as a professional wrestler, he returned to his first love.

“It sure helps me to unwind after some of the rugged matches I run into,” Foti said in the Herald article. “I don’t know what I’d do to relax if it were not for my painting.” His strengths included landscapes, seascapes and portraits.

Less than two years after the feature article, which included photos of Foti painting and in the ring against Stasiak, he was dead.

The obituary in the Calgary Herald — “Well-Known Wrestler Dies At 41” — notes that Foti “spent his life working on canvas. When he wasn’t taking on the maulers of the wrestling circuit, he was recording the beauty of nature on oil canvas, gaining national acclaim for his artistic talents. Mr. Fotie’s varied background had something to do with his far-spread interests. A native of Regina, he started painting for his own enjoyment while in elementary school and used most of his spare time for painting.”

Hayes addressed Foti’s personal demon — alcohol. “He’d be working on his art or doing nothing. He spent a lot of time in the railbar. He wasn’t wrestling full-time. He was poor like everybody else. He didn’t have his own house; I guess he had a house in the past, but that got eaten up somewhere through his booze.”

Though the wrestling world is notorious for wild gossip, the stories that Hayes, in Edmonton, and the Christys, in Los Angeles, tell of Foti’s end are remarkably similar.

Apparently, Foti, estranged from his wife, was living with a roommate.

“John Foti called from somewhere and told the guy he was living with that he was going to kill himself. So the guy called John Foti’s wife, and she said he didn’t have the guts. So he died. The friend didn’t call the doctor or anything,” said Jerry Christy.

Hayes said that Foti called up his roommate and said that he’d taken enough sleeping pills to kill himself, and there was no use coming over because he had the doors locked.

“If he calls you and says that, all he’s doing is asking for help,” theorized Hayes. “This idiot told him, ‘Oh John, don’t worry about it. Go to sleep and you’ll be alright.'”

Foti was officially pronounced dead at Calgary’s Holy Cross Hospital, and he was buried on Friday, May 2nd.

“The doors weren’t even locked. He was asking for help,” concluded Hayes.

While the wrestling world reeled from the suicide, the show had to go on.

“John committed suicide in Calgary on a day he was to have worked in Regina,” said Stampede’s Saskatchewan promoter Bob Leonard. “It was my unfortunate task to have to announce it at the show here; quite a reaction as you can well imagine when it’s a hometown boy.”

The Saskatoon Star-Phoenix reported on the April 30th show, under the headline, “Foti’s death overshadows pro wrestling.”

Archie Gouldie and Mr. Robust won the third fall of their tag team headliner against Angelo Mosca and Don Serrano on Wednesday’s professional wrestling card at the Arena.

Serrano was a main event replacement, substituting for Johnny Foti, the Regina native who died suddenly at his Calgary home early Tuesday morning. Foti’s funeral will be held in Calgary on Friday.