You know you’re a bad guy when a newspaper is running an editorial condemning your actions about a match on TV. Such was the case for Hans Schmidt, who died Saturday.

In this case, it was August 1953, and the editorial writer at the Oneonta (NY) Star had seen Schmidt on the DuMont Network’s broadcast out of Chicago. The German meanie condemned the very idea of sportsmanship during an interview with announcer Jack Brickhouse.

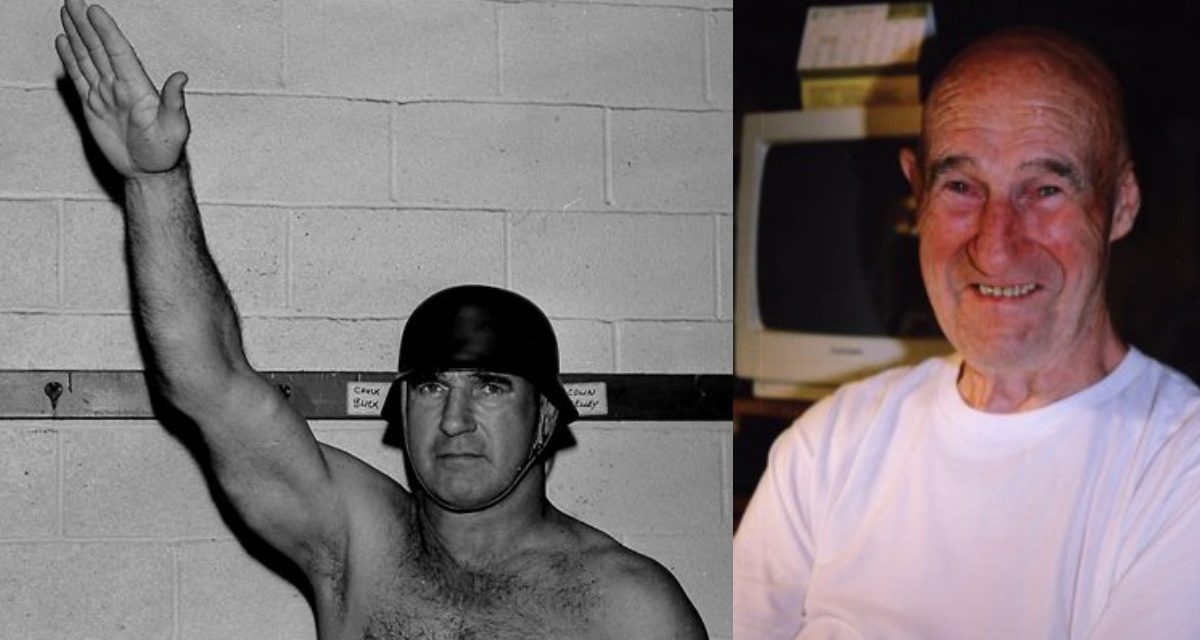

Hans Schmidt strikes a menacing pose in Detroit. Photo by Dave Burzynski

“If Schmidt made his statement with tongue in cheek, it’s poor, Teutonic humor and a slap in the face to the thousands who have been supporting him in this country,” the editorial reads. “Wrestling to us is strictly a scientific exhibition by skilled performers but even the crude in this profession never throw a rotten egg. Schmidt told Brickhouse that he came up the hard way and sportsmanship had no place in his ambitions to win the heavyweight wrestling title and take it back to Germany for keeps. We compliment Brickhouse for ending the interview on this sour note and we hope that millions of Americans who also came up the hard way will boycott Schmidt’s matches in the future and wish him bon voyage to his native land without the championship. This country has no place for a sports figure who refuses to recognize the code which made this country great.”

A lot of the success of Guy Larose, born February 7, 1925 in Joliet, Quebec, came down to timing. He debuted as a pro wrestler in 1949, working under his real name or as Guy Rose or Guy Ross. Perhaps hard to believe is that Larose was a babyface. An October 1950 bout from Lowell, Massachusetts talks about “the popular Canadian, Guy LaRose” taking on “Q Ball” Rush. “LaRose is one of the most consistently popular grapplers to appear in the local shows and will have a big percentage of the crowd rooting for him,” reads the paper.

Boston promoter Paul Bowser thought Larose looked German and changed him forever in 1951.

“You have to remember the era. He was Johnny-on-the-spot shortly after the Second World War when the television era really started in the U.S.,” said Paul “The Butcher” Vachon in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. “At an early age, he had become bald. He didn’t have to shave his head or anything. He was tall, he had a stern look on his face that was not put-on — it was just a natural scowl that he had. And they made a German out of him. It took a lot of guts.”

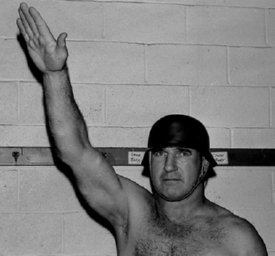

Hans Schmidt lays a big boot into Victor Rivera in 1967. Photo by Roger Baker.

Known as The Teuton Terror, Schmidt became a national star through the booking of Chicago promoter Fred Kohler and his villainous deeds on the DuMont Network, in particular tormenting the likes of smaller babyfaces like Verne Gagne; but then at the time there weren’t many bigger than the 6-foot-4, 250-pound Schmidt.

Dave Meltzer of The Wrestling Observer listed some of Schmidt’s strengths as a candidate for the newsletter’s respected Hall of Fame. “[Schmidt] was one of the highest paid wrestlers of the time. Got NWA world title shots in more different territories than all but the biggest names in the era, indicating his ability to get over in many different places.”

Indeed, there were few corners of North America where he didn’t terrify fans. A typical month in his heyday could see him head out from Chicago to Florida, Denver and New York all during the same month. He made five trips to Japan. He was never much of a title holder since he rarely stuck around long enough to make it worth a promoter’s while to crown him.

“I wrestled so many times. Sometimes I was wrestling six, seven or eight times a week. We had to do TVs in those days, and sometimes on the same day, like a Saturday, they were making tapes and we wrestled two, three times, two three matches in different spots,” Schmidt told SLAM! Wrestling in 2003. “I never wrestled too much in Canada, here, but I know all about the States. I’ve been through it a dozen times to each big city. I lived in Chicago for six years.”

There are few names he didn’t work against either, as Schmidt was so hated that he would turn the local villain into a hero for one night just by stepping in the ring to oppose him.

He was difficult with promoters, and his opinion of them never changed.

“In those days, we used to travel a lot. Promoters were a little bit different than Vince McMahon is. We had only, maybe, five dozen good promoters, but today there’s only one. He’s an asshole. There’s the difference right there. He killed wrestling,” Schmidt said.

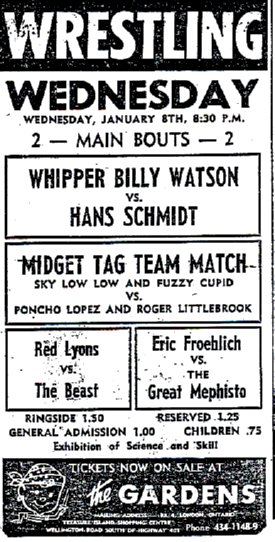

January 8, 1964, London, Ontario

Duncan McTavish recalled Schmidt being doublecrossed by Montreal-based promoter Eddie Quinn in a match in Ottawa. The brouhaha in the arena, with Schmidt losing a belt on a disqualification, was all over the radio shortly after the show ended. “I was with him the day after when he went to collect the money that they owed him. Not a good scene, [it] required the use of a .44 Magnum, scared the hell out of everybody including me,” said McTavish, who died in early 2011. “I think the guy from the Mafia sitting next to Quinn was the scaredest of all.”

Irate fans were an issue for Schmidt, but he insisted he was never scared in the ring. “No, never, but I used to fight like hell to get out of some messes. Some are nuts. I’ve been knifed a few times, but not scared, not really, because it happens so fast you don’t even have time to get scared. I guess, in a manner of speaking, there were a lot of times that I didn’t like going out because we needed protection sometimes like the President of the United States.”

He wasn’t always the most diplomatic with the other wrestlers either, said Eric Pomeroy, who worked as Stan Vachon and Stan Pomeroy. One of Pomeroy’s early bouts was in Buffalo. “I was doing everything that I could do to try to be as good as I could. When I came back into the dressing room, Schmidt says to me, ‘What the hell do you think you’re doing out there?'” Pomeroy recalled. “I said, ‘What’s the matter with you?’ He said, ‘What the hell are you supposed to do in the main event? You’ve done everything that’s normally possible out there.’ I looked at him and said, ‘Schmidt, you might be a big, tough son of a bitch, but I’ll tell you, if you can’t follow me, you don’t belong in the main event.’ He was ready to snap my head off. I was just a kid then.”

By the 1970s, Schmidt had settled into a quieter life in the mountains north of Montreal. Yet he couldn’t get away. “I was on my way out. I didn’t want to wrestle anymore, but they were bothering me. They were calling me everyday. I wanted to quit earlier, but they didn’t want to let me go. They said ‘You’re still good, we need you.’ The territory was down, so they said, ‘Could you help us?’ So I did for a while.” His last run in Quebec for the Rougeaus and in the Buffalo-centered NWF exposed Schmidt to a whole new generation of fans; he even found himself in the odd position of being the babyface in a feud with Waldo von Erich, a next generation German.

Away from the ring, diving was one of his passions. He started when he was living in Newport Beach, California, and his neighbor was a diver. “Slowly, I started diving with him,” he said. “We used to go and catch some abelonea, it’s a shellfish. They stay on the reefs and you have to use a crowbar and take them off. I used to go diving there every day if I had the chance.”

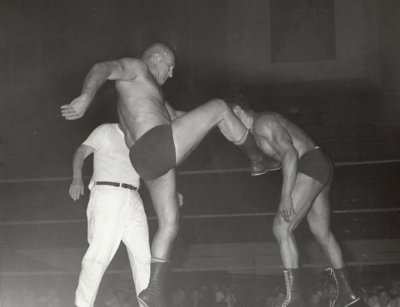

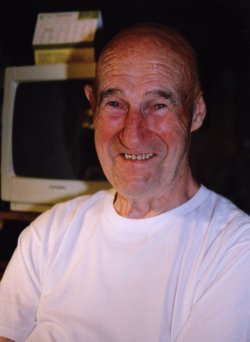

Hans Schmidt in 2004. Photo by Shuhei Aoki

Always somewhat reluctant to talk about his wrestling career, Schmidt positively raved about his diving experiences. “It’s a good sport, it’s real — not like wrestling,” he said, explaining that the lake where he has lived in Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains north of Montreal is too shallow and murky to dive in, so he last dove around 1975. “You were on your own. You had to be careful if you wanted to stay alive. Diving was very exciting. I had my own equipment, I had my own compressor for air.”

He tried to share his love of diving with a number of wrestling colleagues. Schmidt said the famed wrestler/diver Don Leo Jonathan “was scared shitless” when they dove in a quarry near Toledo. “The quarry, it’s very clear when the sun is shining, but it’s a funny place to go, with a lot of small tunnels. If you have a rope, you can go in those tunnels, but without a rope, you’d better not go, to find your way back. Don Leo didn’t want to go there at all.”

Others who dove with him included Bill Melby and Bobby Managoff, who had real trouble because he couldn’t see very well without his glasses. But it was telling stories of Sky Hi Lee that got Schmidt laughing. “We were in Hawaii, and I took him down and I nearly lost him. That was the last time. He took off on his own and didn’t have any experience. That day, the boat we were with, there was no anchor, so I told him to stay with the anchor! He was looking for the anchor and we lost him. I found him, but it scared the hell out of me. I said no more.”

Schmidt moved to Entrelac to escape the city life, and even in his last years, would be on the roof, clearing the snow. The lake itself evolved over the almost 40 years he lived there into a playground of the rich.

While dismissive of today’s wrestling — “I watch it on TV once in a while, and I get all upset and I don’t want to watch it anymore! They’re a bunch of clowns.” — and quick to deflect conversations away from his own glory days, Schmidt never could get away from his past. A couple of years ago, two Japanese reporters showed up unannounced at his doorstep. “They came into my place by cab, a taxi from Montreal. You know how they found me? They called the taxi company, and they asked if the driver knew who I was and where I lived. By chance they found one guy who knew where I lived. They hired him and he took them to my place, where I saw them. I couldn’t believe it,” Schmidt chuckled, imagining the hour-and-a-half cab ride from Montreal. “They stayed about half an hour then they took off.”

In recent years, Schmidt’s health deteriorated, especially because of arthritis. His stomach was the cause of a hospital stay in the spring of 2006. “They fixed it up. I’m okay now. I nearly kicked the bucket, but it just didn’t happen. Only the good die young.”

Jacques Rougeau Sr. was one of the few from Schmidt’s wrestling days that made the effort to stay friends and visit him. “I go and see him every year, once a year, and spend a couple of hours with him. We talk about old times,” said Rougeau Sr. in the fall of 2011. “He’s always sitting on a chair all day, not moving, he can hardly walk.”

His stepdaughter, Nathalie Delorme, said that Schmidt had been in the hospital a couple of weeks, and developed fluid on his lungs. “He kind of just faded away slowly,” she said. “He was such a strong man.”

Schmidt’s passing at the age of 87, on Saturday, May 26, leaves a major hole in the history of pro wrestling. After all, as he once said, “I wrestled with almost everybody, except Santa Claus.”

The funeral for Guy Larose will be Wednesday, May 30, at 10 a.m. at the church in Entrelac. He is survived by two children, Guy and Diane, and two grandchildren, David and Ian, as well as his wife of 28 years, Monique Moreau, and her children.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 22, 1998: Hans Schmidt a reluctant interview

- May 28, 2012: The imprint of Hans Schmidt