It’s only fitting that before trying his hand as a professional wrestler the would-be “Superstar,” Bill Dundee, worked for a traveling circus. While an animal handler for the Australian road show, the rough and tumble William Cruickshanks learned a thing or two about how to capture an audience’s attention and, more importantly, how to hold onto it.

“It’s the same thing (as wrestling), but a little bit different,” says Dundee about the parallels between the circus life and his life in the ring. “The circus was there to entertain, so you watched what they did and didn’t do. The carnival was a different thing because you had all the games of chance where the (spectators) never won. You never gave the money away.”

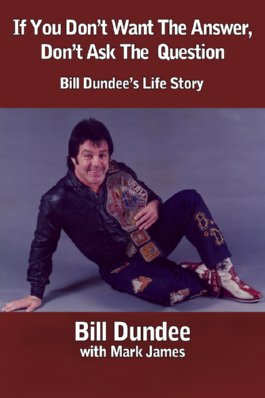

Dundee’s new book, If You Don’t Want the Answer, Don’t Ask the Question, begins with some insight into the Scottish-born Cruickshanks’ childhood and the short time he spent with the circus, as well as at assorted 9-5 jobs. From there, Dundee basically gives an abridged version of his life story in wrestling.

That long journey, still being written, began stateside in 1974 when he and tag team partner George Barnes landed in Nashville to work for infamous Tennessee promoter Nick Gulas right off the plane from Australia. Dundee had already sharpened his ring chops before leaving Australia while working there for Jim Barnett and other promoters during the late 1960s. “At that point in my career, I was officially a professional wrestler,” he writes about quitting his day job at a refrigerator factory in favor of working for Barnett’s NWA affiliate.

The book, Dundee’s first, tends to avoid cheap shots. Instead, the Superstar gives an insightful, even educational, look at how wrestling’s territory system functioned in the ’70s and ’80s, as well as how it floundered during the early ’90s. The no-nonsense history lesson should be of interest to both longtime wrestling fans and younger mat archivists who never had a chance to view action from the numerous regional promotions when it first aired.

“People don’t go out to the matches now like they used to. When Memphis was real hot, people came from all over — Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Indiana. You’d go out to the parking lot and look at the car tags and they’d all be different,” remembers the Superstar.

Dundee also makes his opinion known of several names who he respects or who’ve run afoul of him throughout the 250-page read, co-written by Memphis ‘rassling historian Mark James and edited by Dundee’s friend, former jack-of-all-Memphis-trades Randy Hales. But, in a twist not always seen in books penned by wrestlers, Dundee chooses not to throw his fellow competitors under the bus or spill too many incriminating beans about wild times spent on the town after the matches.

But that doesn’t mean we’re not privy to some behind-the-scenes reminiscing best enjoyed by adults. After all, as Dundee confirms, most Memphis fans held local wrestlers in the same regard as rock stars, especially during the ’80s Jerry Jarrett-run era. In one chapter, Dundee recalls almost coming to blows with Memphis rock ‘n’ roll icon Jerry Lee Lewis one night when the self-proclaimed Killer refused to relinquish a nightclub stage to Plowboy (Stan) Frazier. The behemoth Frazier, who later had a WWF stint as Uncle Elmer, was scheduled to make his debut there as a country singer.

“You never saw Elvis (out in public), but the Killer was always hanging out somewhere. You’d go to a nightclub or bar he knew and he’d be sittin’ there singing and drinking,” Dundee recalls. “It was a whole different kettle of fish than it is nowadays. When you walked down the street, people would scream at you and holler from their cars. If you ever had to go to a high school to publicize something, (the reception) would be unbelievable when you walked into it.”

A vast majority of If You Don’t Want… focuses on Dundee’s many years in the Memphis territory. It was there the two-fisted spitfire Championship Wrestling commentator Lance Russell liked to call “The L’il Aussie” constantly alternated between heel and babyface, thus becoming one of the promotion’s most loyal and prominent stars — second only to Jerry Lawler in terms of time spent in Memphis’ main event spotlight. In the wild Mid-Southern area, Dundee learned to use his believable promo style and natural toughness to get over — and stay over — for decades, despite being smaller than many of the other wrestlers.

“Most places didn’t have the history that Memphis had. It was a history that just kept on going,” says the Superstar. “It was the only live hour-and-a-half show coming into people’s houses every Saturday morning. Nobody else was doing that. But, what made it really special from 1975 till now was Jerry Lawler and Bill Dundee. I don’t mind telling you that.”

Much is said in the book about Memphis’ two king Jerrys — Lawler and Jarrett, as well as the at-times combustible relationship between the three. It’s difficult to imagine the wild and inventive promotion’s halcyon days (’81-’86, Dundee figures) without that memorable trio of personalities.

A never-ending rivalry and partnership between Dundee and Lawler found the two competing in just about every type of gimmick match imaginable. Loser leaves town matches, cage matches, hair matches, tornado tag matches and the original Tupelo Concession Stand Brawl (an oft-acknowledged precursor to “extreme” wrestling covered in depth with its own chapter). You name it. Whatever the scenario, the two men were essential to the raucous, homegrown brand of Memphis wrestling where, as Dundee, Jarrett and Lawler agreed, personal issues drew money.

“Very few guys did what Jerry Lawler and Bill Dundee did — stay in the same territory for 25 years wrestling against each other, as partners and whatever else. Whatever it was we did, people seemed to like it. Part of that was because Lawler and I never were big buddies. We had respect for one another when it came to working, but we didn’t hang out away from the ring. He didn’t drink and I did. I was kind of wilder than Lawler back then. There was truth there. People made up their own opinion that we didn’t like one another. They thought that I didn’t hang around Lawler away from the ring and they weren’t lying.”

Of Jarrett, Dundee credits the wrestler-turned-promoter as the brains behind Memphis’ rise in popularity during the early ’80s. But, as time went on, Dundee writes that Jarrett became more like their old boss, the oft-derided Gulas, who Jarrett broke away from to kick start the Memphis promotion. The similarity wasn’t only in how Jarrett dictated payoffs to the wrestlers, continues Dundee. He points to the extensive push of Jarrett’s son, Jeff Jarrett, as a contributing factor in the decline of Memphis’ drawing power. Years before, Gulas had done the same thing with his son, George, to less-than-favorable results.

“Jerry Jarrett was a very smart businessman. You can’t take that away from him,” credits Dundee. “He put it all together by taking it from the (Ellis) Auditorium downtown to the coliseum in Memphis. He was a big part of doing it right and he had good help, too. Then, you had (commentators) Lance Russell and Dave Brown who were like our Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra. Both singers, but with different styles.”

Though it was sometimes described by detractors and rival promoters as “bullshit” or “lazy” wrestling, the Tennessee style of build-up and booking has stood the test of time — a fact that Dundee readily confirms. Numerous angles that highlighted Memphis TV programs and live cards — such as heel wrestlers hiding beneath the ring in efforts to sabotage a match — have since been recreated in various eras of the WWE. “I watched all the shit Lawler did with [Michael] Cole and that was all just Memphis stuff,” Dundee said in reference a recent angle that pitted the two WWE commentators against one another.

It was in Memphis, too, that Dundee first booked a wrestling promotion — a decision he also credits to Jarrett. That aspect of his career also receives much attention in the book. Dundee documents how booking offices functioned in just about every promotion he worked for, including Bill Watts’ Mid-South, Ted Turner’s WCW and the Fullers’ Alabama/Knoxville territory. In Dundee’s opinion, an effective booker first had to genuinely want to do the job day in and night out. Then, a good booker, which Dundee likens to a puppeteer, had to be willing to put enough time in to create a card or program that gave the fans more than just a solid main event.

“Most of the guys couldn’t book themselves (effectively), much less a whole territory. If it was that easy, everybody would’ve been doing it,” says Dundee. “There’s different styles of booking, too. Somebody like Dusty Rhodes was very good at being the booker as long as he was booking himself. Lawler was the same way. Jarrett and I did it (with the belief) that somebody had to book the whole card. The first match had to show up just like the last one. You really had to know what you were doing. You would go all day at the wrestling office doing stuff and then go wrestle towns at night. You didn’t have a whole hell of a lot of time to do all the other things that the boys were doing.”

If You Don’t Want… also touches upon the two years Dundee spent in Watts’ Mid-South promotion and, later, WCW during the few months that Watts ran the show there. The Superstar says that when Eric Bischoff began calling the shots and signing former WWF superstars to high-dollar WCW contracts, he knew his days there were numbered. “(Bischoff) was a prick who kissed the Turner execs’ asses and then, later, kissed [Hulk] Hogan’s ass … it was a miserable working situation,” he writes.

But just as his life in wrestling often did, Dundee’s narrative always goes back to Memphis. “Memphis is where I spent most of my life. I worked for Turner, Watts and Crockett; I worked in Florida and all around. But Memphis was where Jerry Lawler and I were the two mainstays for 30 years,” he says. “Jackie Fargo, Billy Wicks and Sputnik Monroe were all big stars there during the ’50s right up into the ’70s. They passed the torch along to guys like Lawler and me.”

Throughout If You Don’t Want… Dundee elaborates on the differences between how business was done in the territory days and how it’s conducted today. In fact, an entire chapter of the book lists comparisons between wrestling then and now. For example, he writes, “Now: You’re lucky if you can fill up the same building twice a year. Then: We did it every week.”

“Back then, there was room for doubt. People knew Lawler was mad at Dundee and they were going to have a hell of a fight come Monday night. That was what you sold out with. Now, it’s just a show for TV and they tell you it’s just a show. There’s no Dusty Rhodes-type character, no Austin Idol or Handsome Jimmy [Valiant]. We were all different then. Guys were 300 pounds or had an awesome body like Idol or long hair, tattoos and a beard like Jimmy Valiant. Now, it’s all about a cookie-cutter image.”

In recent years, with yet another twist even the craftiest booker wouldn’t have thought up, the 68-year-old Dundee returned to the circus. He began working alongside friend and former Southeastern/Continental Wrestling fixture Ron West in a marketing position for the traveling Cole Brothers Circus. But, in early 2011, Dundee took the rest of the year off to complete his book and have some knee surgery done.

“You know what talks and you know what walks, right?” laughs Dundee when asked whether or not he’ll return to the circus after he finishes promoting the book at spot shows around the south. “It’s an option and you always keep them open.”

Bill Dundee now.

Today, Dundee still calls Tennessee home. He says he’s still recognized on the streets of Memphis, even though the area hasn’t had a successful wrestling TV show in years. He still wrestles, too, and says he’ll soon be climbing into the ring more frequently — mainly on the Southern indie circuit — now that he’s recuperated from full knee replacement surgery done last November. “My good one is really my bad one now,” says the Superstar of his retooled set of hinges. “I’m starting to think my good one ain’t as good as I thought it was since I got this new one (put in).”

Dundee’s first foray into autobiographica stands well on its own and is also a great companion piece to the recent documentary Memphis Heat, in which he and Lawler are both prominently featured, as well as a new shoot interview/career highlight set (Memories of a Superstar) that Dundee recently completed with Tennessee wrestler/promoter Beau James.

It also provides a contrasting view of Memphis wrestling history documented in books written by his onetime colleagues Jarrett and Dutch Mantell. Dundee contends that his book presents some situations differently and, he stresses, more truthfully.

“I looked through Jarrett’s book and Dutch’s book to see what they wrote so I could correct it! I called Dutch (about some things in his first book) and he said, ‘What’s the name of my book Bill?’ When I said The World According to Dutch, he said, ‘There you go, you can write your book any way you’d like,'” laughs Dundee. “My book is how I saw the wrestling business. I didn’t do the book to crucify anybody and there’s ways of saying things without going on like an idiot. But, I still have a whole lot of my old booking sheets and paperwork to prove (what I’ve written). Five years ago, I never would’ve done an interview like this or knocked the wrestling business. That’s why it took so long for me to write a book, I guess. But everybody’s smart today and everybody talks about it. If you were smart, before, you had to be in the ring. I was in the ring. I know what we did and why we did it.”