During a career in pro-wrestling that’s seen him wrestle, manage, book and call the action, the man born Wayne Keown has garnered more than a few nicknames. Among them, the Dirty Dutchman and “the Mayor of Oil Trough, Tx.,” according to beloved Memphis announcer Lance Russell. Less flatteringly, an antagonistic Jerry “The King” Lawler, once deemed the bristly-backed Dutch Mantell a “human Chia Pet.”

First and foremost, Mantell is a survivor. Before stepping into a wrestling ring, he survived 11 months and 29 days in the jungles of Vietnam while serving with the U.S. 25th Infantry Battalion. He’s also a survivor of the ring wars — a rough, ornery character who came of age during the territorial era of the late 1970s and ’80s. In the Southern U.S., where the now Tennessee resident did much of his work, regularly scheduled wrestling was as commonplace then as church on Sunday morning or raising Hell the night before.

“A lot of times we worked certain towns 52 weeks a year,” Mantell recently told SLAM! Wrestling. “Wrestling would be in Memphis, Louisville, Nashville, Evansville or wherever every week of the year. You had to learn how to tell the story and make it interesting to keep people coming back. You had somebody like Jerry Lawler or Jerry Jarrett, who were the bookers at the time, and they knew what they wanted. They were also gifted in that they had the players to play the game. They would call the plays and we would run them.”

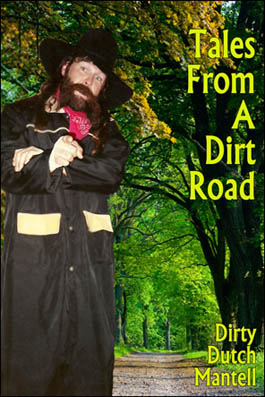

Inspired by his online blog, The World According To Dutch, Mantell is also making a name for himself as an author or, as he prefers, a storyteller. Tales From a Dirt Road is Mantell’s second collection of true, often hilarious stories taken from over 35 years on the road and inside the squared circle. Working arduous schedules during those years that allowed for little to no downtime, Mantell says he has no shortage of tales left to tell.

The over 300-page Tales picks up where Mantell’s first book, also entitled The World According To Dutch, left off. Neither book is a straight-up autobiography, but, instead, both are filled with an eclectic mix of road stories that Mantell either experienced firsthand or was told by his colleagues. “In the books, I tell stories of backstage fights, barroom brawls, wrestling in a maximum security prison and getting stopped by state troopers then being pulled out of the car at gunpoint. These are not your typical wrestling books.”

In Tales, Mantell also shares his thoughts on how business was done in both wrestling’s heavily kayfabed territory days, as well as in the modern era. His time spent in the WWF under the alias of hillbilly Blu Brothers kinsman Uncle Zebakiah is also touched upon. Unlike some books penned by ex-employees of the former Fed, Mantell does not use the format as an opportunity to bash the McMahons or their company.

“This is a temporary business. You can’t expect it to last your whole lifetime. Plus, I didn’t write this book to air my grievances. Do I have grievances? Sure, we all do. But, do I think anybody else wants to hear them? I don’t think so. If I was reading a book and somebody did that it’d piss me off. If the guy wrote another one, I wouldn’t buy it. I enjoyed my time in the WWF. In fact, I think Vince McMahon’s still one of the most old-school bastards out there. He’s stuck to pretty much the same formula over the years and knows what it takes to get a guy over. Look at The Undertaker; that’s Vince McMahon. He invented him. I think that’s why Undertaker won’t ever lose at Wrestlemania, because he’s Vince’s most personal creation.”

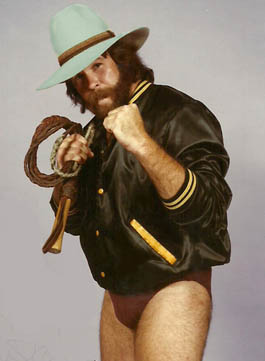

Throughout his in-ring career, the bullwhip-carrying Mantell was known by fans as a tough talking, no nonsense character who got his point across not by shouting or making grandiose gestures. Instead, the Dutchman spoke his piece clearly and deliberately, seldom allowing anger boiling beneath the surface to get the best of him. Mantell remembers that an early mentor, original masked Assassin Tom Renesto, was very influential in teaching the young up-and-comer how to make the fans believe what he put across.

Dirty Dutch strikes a pose.

For old-school Southern wrestling fans, one of the new book’s funniest stories will be that of an early paying gig that saw Mantell wrestle as a “jobber” for Jim Barnett’s Georgia Championship Wrestling out of Atlanta. It was there Mantell first met Renesto, who was working as the booker for the NWA’s Georgia office. As the story goes, Renesto assured the young grappler that if a steady paycheck was sought, Mantell was expected to show up and participate in each and every event at which he was scheduled. Even if that meant wrestling outdoors at a sweltering Atlanta car lot on a “100-plus-degree” summer day.

“Back then, if you didn’t work you didn’t get paid and if you got hurt, a lot of times you just had to work through it. Tom Renesto was a good guy to me and I learned so much from him. I would ride up and down the roads with him a lot and pick his brain. If you can’t learn in that situation, you’re just not going to learn. Tom Renesto and Jody Hamilton were the Assassins, of course. They wore those masks and never raised their voices. That was actually a great selling point because it made fans think they were deadly and meant business. Timing is something that is very difficult to teach and both of them had great timing. They always say you have to watch out for the quiet ones.”

Though titled Tales from a Dirt Road, many of the book’s stories were actually born along the maze of narrow, two-lane blacktop that zigzags across the U.S. In several late night situations that arose after the matches were done, Mantell was an innocent bystander who became a human bridge between disaster and narrow escape. Take, for instance, the WCW “tour from hell” for which he traveled in the same rental car as Sid Vicious, the trip’s navigator, and the unpredictable Iron Sheik. Then, there’s Dutch’s nervous recollection of how swiftly an inebriated future Undertaker, then “Mean” Mark Callous, once responded when challenged by a mouthy barfly. All the while, Mantell remains an engaging narrator whose gift for gab and delivering a good laugh are not lost in the transition from spoken word to print.

Not all the book brings chuckles, though. Its most serious chapter chronicles Mantell’s time spent in the Florida territory run by the late Eddie Graham. Mantell says that Graham was one of the men who helped him learn the business and that Graham’s 1985 suicide came as a shock to everybody who has ever worked the Florida territory. “Whatever it was, it had weighed terribly on Eddie’s mind. And the result was a terrible tragedy. To me, Florida wrestling will always be Eddie Graham and after being around him, I found out it was guys like Eddie who made me love this business in the first place,” writes Mantell.

Now a resident of outer Nashville, Mantell says the hottest and most faithful U.S. crowds he ever performed in front of were found in the South. Two promotions he frequented during the 1970s and ’80s were Jerry Jarrett’s Memphis territory and the Fullers’ Continental promotion centered in Alabama. In Tales, Mantell describes both as “wide open, with excellent talent and good TV.” However, the wild and wooly antics of Tennessee and Alabama paled in comparison, he acknowledges, to the downright life-threatening situations experienced on the isle of Puerto Rico.

“Puerto Rico was in a league of its own, buddy — nothing but flat out wide open and crazy. You could really get hurt there. One reason is that the fans drink like fish. You really had to watch the crowds because you might get beat on before you even got to the ring. Tom Renesto had warned me about that white heat you would get there when the fans got angry. When they started coming, I knew what he meant. It’s the only place I worked where, at times, I had to actually fight the fans on the way to the ring. In Trinidad, I had glass beer bottles thrown at me. That’s one reason I started wearing ponchos. They put another layer between me and the fans.”

Nowadays, Mantell, age 61, continues to make a living through his involvement with pro-wrestling. He still climbs into the ring on occasion and, along with his books, he’s also the dean of the University of Dutch, a wrestling school located outside of Nashville. Main eventers who benefited from his on the job training while coming up include Kane, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin and TNA’s Abyss, a creation of Mantell’s chronicled in a revealing chapter of the book.

“I’ve had to learn how to really teach these guys how to do certain moves. It’s not as easy as it sounds. When I was steady wrestling, I never really thought about the mechanics of doing a move. I just did them. But now, when I’m trying to teach it, I have to take a step back and look at how it’s done from a different perspective. I enjoy it, though, and I think a lot of kids never got very far in the business because they went to inferior training facilities and had trainers that just took their money but didn’t teach them anything.”

Mantell with collaborator/distributor Mark James.

Perhaps one reason Mantell’s books have reverberated so well amongst fans of old-school wrestling is that Dutch was honing his craft as a storyteller years before he picked up a pen to record the memories. He winces at how newer grapplers are presented in the modern era, acknowledging the abundance of similar, chiseled looks and whitebread personalities. With very little truly outrageous characters still in the mix, he also finds something amiss with the lost art of the interview or promo. Previously a crucial element in how a wrestler got over with, or agitated, fans, Mantell says that scripting the dialogue of today’s superstars is robbing wrestling of both its unpredictability and visual appeal.

“When I started, they didn’t write down what you were going to say on a piece of paper. They said, ‘Kid, here’s who you’re going to wrestle. Now, go sell some tickets.’ You had to create your own character. I still think if a guy can talk, let him talk. I don’t care if a good talker is in a grocery store, a barbershop or wherever, if he can talk, let him talk and allow his own personality to emerge. Plus, most of the guys I see on WWE now all look the same. They all are 5’10” to 6’2″ tall and weigh 210 to 230 pounds. Every one of them looks the same. They all look like juniors in college. Where are your Abdullah the Butchers, your Bruiser Brodys, your Lawlers, your Jos Leducs or Stan Hansens? All those guys were larger-than-life characters who could talk. Where are they? Sad to say, but they aren’t there anymore.”

Mantell does acknowledge, however, that today’s wrestling product cannot be accurately compared to that of the past, partly because a nationwide job market for full-time wrestlers no longer exists. “They’re two different animals, then and now. You don’t have all those places anymore where young wrestlers can develop their characters and learn from the veterans,” he says. The territory days may be gone for good, but through the writings of an opinionated, traveled alum like Mantell, at least fans of the good ol’ days can find out more about what went on in the cars, bars and motel rooms, as well as behind the curtain of pro wrestling’s most influential and, some would argue, most entertaining era.

“These are the same stories I told going down the road years ago. All I did was put ’em down on paper. Unless stories like these are documented in print, they’re just going to fade out and die. The way the territorial system operated is never coming back. The only way you’re going to hear about it is in a format like I’ve chronicled in my books. It was a magical time, much like the old Wild West. But, it also had a limited run of about 40 to 50 years. It was a lot of fun, but it’s never coming back.”

(New blog entries and autographed copies of Tales from a Dirt Road and The World According To Dutch are available online at www.dutchmantell.com or by e-mailing dirtydutchmantell@gmail.com.)

DUTCH MANTELL LINKS

- Nov. 13, 2024: Mantell wants to ‘slap the dog s–t out’ of Meltzer

- Feb. 24, 2010: Dutch Mantell happy to share his wisdom, experiences

- Feb. 7, 2010: What Dutch Mantell’s book lacks in facts it makes up for in stories

- www.dutchmantell.com

Michael Andrews is making his SLAM! Wrestling debut. When not moonlighting as a wrestling writer, he works for a weekly newspaper in north Georgia. A longtime fan of the old Southern territories, he still believes the best way to settle a dispute between coworkers is a Hair vs. Hair or Loser Leaves Town match.