“Why the hell am I doing this to myself?”

That has to be the question many wrestlers, especially those struggling to reach greater heights by way of the independent circuit, habitually ask themselves.

Of the thousands who try, only a select few make it to the big stage, and fewer still become main eventers there.

Many of the would-be wrestling stars of tomorrow first get drawn to the spectacle known as professional wrestling as children watching their favourite stars hammer each other into oblivion on TV.

The obsession eventually grows to the point where they think that they too could get into the squared circle and entertain fans around the globe.

But most discover the road to stardom is a grueling one to journey, especially during the early days of punishing training and subsequent arduous road tours.

“They see wrestling on their TV every week and it seems thrilling, but they don’t realize that there is a ton of time away from home, family and friends,” said Winnipeg, Manitoba’s Chi Chi Cruz (a.k.a. Corey Peloquin), a 20-year veteran of the business.

TV has a tendency to show only the glamour of the sport, not the travails that led to the glory.

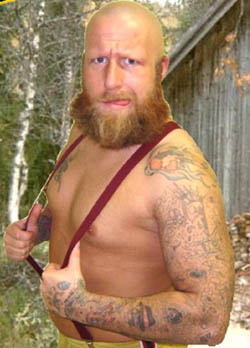

“Lumber” Jack Johnson (a.k.a. Jason Collier) was once evicted from his apartment when he could not pay the rent. But refusing to give up on his dream of becoming a wrestler, the Nova Scotia-born Johnson slept at Toronto’s Pearson Airport and showered at a gas station while still attending training sessions.

“That lasted two-and-a-half months ’till the classes ended. Then I was on the first bus back home to Cape Breton,” Johnson said, adding that once he arrived home, he had to go through another wrestling school to pick up some work. (After completing numerous other training schools, he went on to wrestle for MainStream Wrestling in Canada’s East Coast.)

“Lumber” Jack Johnson

Scotty Mac, who wrestles for British Columbia promotion Extreme Canadian Championship Wrestling, revealed the highly educational nature of his initial workouts.

“After my first training session, I remember getting a ride home with my girlfriend at the time, and I had to pull over and throw up. When I woke up the next morning, I had a hard time getting out of bed,” said Scotty Mac, who requested his true identity remain anonymous.

“Kowboy” Mike Hughes (a.k.a. “Hangman” Hughes) remembered touring with Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling after 10 one-hour sessions with René Dupre, his father Emile Dupre, and Hubert Gallant, and facing a less than magnanimous opponent during his first match.

“I was put in the ring with Bobby Bass and all he did was squash me and take advantage of me. He was a real ass and the Cuban Assassin came to my aid,” the 6-foot-5, 260-pound native of Stratford, Prince Edward Island said.

Hughes added Assassin thereafter became something of a mentor to him, teaching and helping build his confidence: “I owe the Cuban everything; he taught me how to be a pro.”

Luckily for Kingman/Brody Steele (a.k.a. Peter Smith), a 6-foot-6, 300-pound “monster,” his immense size precluded abuse.

“I was first trained by Emile Dupre then went to Calgary and furthered my training with Leo Burke. I could have kicked any trainer’s ass in the world before I got trained, shoot, so that was never a concern of mine,” said the Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia resident.

Stu Hart once lamented the state of today’s wrestling schools, calling them “dancing schools,” and other wrestlers have echoed his sentiment about unqualified trainers too.

“These ‘swchools’ are killing the business,” said Kingman.

Winnipeg’s Rawskillz (a.k.a. Bryce Ridgen), without naming names, said there are a couple of organizations in Winnipeg that run schools with trainers that are not properly trained themselves. “It’s a dangerous sport when guys don’t know what they’re doing.”

Cruz agreed: “Always be careful of trainers who never did a thing in their careers, because really, what can they truly teach you?”

The tours can be just as devastating as the training, and perhaps more so. Just ask anyone who has competed in and completed famed Winnipeg promoter Tony Condello’s annual Northern Tours.

“If you can survive those you can survive any promotion,” Condello said, noting the inherent dangers of these freezing winter excursions into northern Manitoba Indian reservations. “If you don’t know your way, you’re not going to make it back.”

The veteran of 30 such tours, (which Don Callis dubbed “Death Tours”), said a lot of guys have backed out of the trips after being unable to cope with the adversities.

Death Tours represent a mental as well as physical test, as wrestlers endure temperatures that can dip to 50 degrees below zero Celsius, and multi-hour drives across frozen lakes and tundra. Condition improve little once arriving at a destination, as the talent is forced to sleep on mats on gym floors, wrestle every night, and cook for themselves because of few if any available restaurants.

Bringing food along is a must, unless a performer is willing to pay about four times the typical cost of provisions, Condello said. (The exorbitant cost is due to the challenge of transporting food to these northern hamlets.)

Some of the notables who have survived the tour include Edge, Christian Cage, Rhino, Chris Jericho, Test, Lance Storm, and Cruz.

“If you aren’t sure you want to be a wrestler, you’ll know after living through one of those tours,” said Cruz, who has been on every Death Tour since 1990, save maybe two or three. “Most guys don’t realize the tremendous amount of time it takes to travel between shows and how boring it is to deal with.”

Travelling from one destination to another (not including harrying circuits into the wilds of Canada’s north), can also be a heavy financial burden for wrestlers as many must pay their own way.

“Young guys have to pay for it more because they need the experience and if they are unknown, then who is going to pay to see them? You spend your career building your name and your worth,” said Cruz, who at this stage of his career can get promoters to pay for his transportation.

Rawskillz works only in Winnipeg partly because of the expense in moving province to province.

“It costs a lot to get your name out there,” he said, adding he also stays close to home because he is attending university to earn an Education degree.

Those who withstand the training and begin travelling the indy circuit soon discover wrestling is not necessarily the gateway to riches.

“My first match, I got an envelope with $10 in it,” said Scotty Mac.

Although his pay has since improved, he still needs the income from a second job to live on his own. Complicating matters is every job he takes outside of wrestling must accommodate bookings he gets: “Wrestling is my number one priority.”

“It’s really tough to be able to stay on top of bills, rent, gym membership, food and all the other necessities in life and still keep the drive and desire to keep on going in the business that is going to make you or break you,” added Johnson.

Rawskillz said there is not much money to be made for the typical indy wrestler, with guys averaging $20 a match. If travelling, some guys can makes upwards of $100 a card, but that is not the norm, he said.

When Rawskillz first started out, his goal was to one day go an entire year making a living from wrestling, but that never panned out.

“There’s a lot of talented wrestlers out there. You’ve got to totally dedicate yourself,” Rawskillz said.

Cruz said he has made a living exclusively wrestling at many points in his career, but emphasized holding down a back-up job is a smart move to ensure one’s bills get paid. Even now, Cruz said he works security at a Ramada Inn in Edmonton, Alberta.

The business can also put great strain on personal relationships.

“A lot of times my girlfriends don’t like my wrestling character. And they don’t understand why they can’t come on tours,” said Scotty Mac.

“I wrestled 32 matches from April 21 to May 18, 2006, mostly against former ECW star ‘High Flying’ Chris Hamrick,” said Johnson. “Wrestling a schedule like (that) really takes a toll on your mind, thinking about your wife and child at home, and your body, from night after night of bumping, lack of sleep and travelling sometimes nine hours to the next town. But in the end it’s worth it.”

Working regularly in Europe among other places since 2002 has often kept Kingman away from home: “I am lucky to have an understanding wife. I’ve been gone for months at a time very many times.”

“You sacrifice so much that it becomes hard to explain,” said Cruz. “I have left friends, family, and girls I loved behind in order to make a name for myself in wrestling.”

But those vying for the top are willing to sacrifice almost if not everything, including their health, to perpetuate their careers.

“I was on the road 157 nights straight my first tour. I wrestled through a lot of injuries including a torn quad and never complained,” Hughes said.

He said Cuban Assassin took a picture of his torn quad and displayed it on the refrigerator in his apartment. When another wrestler griped about a pain in his shoulder, Assassin pointed to the picture and said, “That kid hasn’t complained once. What’s wrong with you again?”

The most ambitious of wrestlers accept and endure their assorted trials and tribulations to attain their ultimate goal, which most commonly is getting a job with the WWE or with a Japanese promotion.

“I would love to work for WWE but living in P.E.I. doesn’t give me a lot of exposure or access to tryouts,” said Hughes. “They don’t come to you like other sports recruiting, you have to go to them. TNA is also very appealing to me. I’ve worked with a lot of their guys in Puerto Rico and the talent kept asking me, ‘Why don’t you come to TNA?’ So who knows?”

Hughes also wrestled with New Japan Pro Wrestling in 2005 and has plans to return.

“I’ve had hundreds of matches, but in terms of WWE, they’re a step above everyone else,” said Scotty Mac, who attended a WWE training camp in Louisville, Kentucky last year and called it a humbling experience. “They even teach the basics differently. There is so much to learn. Even guys who’ve been wrestling for years and years, they don’t know as much as they think they do.

“There’s a reason they’re (WWE) in the spot they are. They set the standard. WWE’s the place to be in.”

Although many Canadian wrestlers applied to attend the September WWE tryout in Ottawa, Kingman felt such events were a waste of time.

“WWE tryouts are a joke. They want you or they don’t,” Kingman said. “I work as often as I like for All Star Wrestling in the U.K., and sub contract myself to other one-off groups while I’m there.”

Cruz thought the tryouts made it easier for wrestlers to get a chance to catch WWE’s eye, but admitted he is not actively pursuing a spot in that organization.

“I am not giving up hope either, I have merely readjusted my goals,” said Cruz, whose current goal is to get a TV show idea, a wrestling-based comedy, filmed and produced. “I am happy helping young guys develop their talent too. I help the younger wrestlers in Monster Pro Wrestling and Power Zone Wrestling and it is nice to be appreciated.”

Rawskillz also is no longer looking at making his future all about wrestling. “It is so physically demanding and the reality of it is not a lot of guys will make it. It’s sort of a weird dynamic. I’m realistic about it — I do it for fun … when the match is over and I’m proud of it, it’s like a piece of art.”

Still, Rawskillz said he aspires to one day wrestle in Japan, saying he preferred the style there over that of WWE because the Japanese matches focus more on competition and sport than “wacky storylines.”

Rawskillz felt WWE did not put much stock in a wrestler’s experience and pedigree, instead placing much greater emphasis on those who completed its own training camps. With fewer performers working their way up through the ranks, there is little to differentiate the newer talent, he said.

“Most of today’s stars don’t have the charisma that was there before,” Cruz added. “I think it’s due to pushing guys before they are ready. They can do the moves, but that connection with the crowd is absent.”

Hughes agreed, pointing out a lot of “cookie-cutter wrestlers” lack a feel for the crowd or their craft. “In this business, I feel the best way to learn is working as many different people and styles as possible in as many different countries as possible. In Europe and Japan the style is technical and stiff, in Puerto Rico it’s brawling and violent with some lucha libre… In this business you never stop learning.

“When Undertaker, Flair, Benoit, Booker T, Finlay and Regal are gone that’s the end of the great workers — the end of the old schoolers.”

Many bemoan the loss of the “old school” mentality in wrestling and feel it is sorely missed.

“Emile paid me well for a green guy but I paid my dues and earned every penny,” said Hughes. “I worked twice a night, set up and tore down the ring, etcetera. I was brought in properly and learned to respect the business.”

Cruz said the scene has changed a great deal, where many of the young guys want to perform all their “cool spots” every match, which often comes at the expense of telling a good story in the ring.

Traditionalist Condello, however, revealed some things never change, and stressed wrestlers still need to remember five basic rules if they want to make it: Listen, mind your own business, don’t complain, show respect (“Yes sir, no sir.”), and be on time.

“Otherwise, the business will chew you up and spit you out.”

CHI CHI CRUZ STORIES

- Apr. 6, 2007: Chi Chi Cruz the calm in Stranglehold’s storm

- Aug. 18, 2004: In praise of Chi Chi Cruz

- July 2, 1999: Chi Chi Cruz had to get out of Winnipeg to improve