Scott Norton is on a break from professional wrestling, his first in 17 years. But that doesn’t mean he’s not involved anymore. Instead of lacing up the boots himself, the former IWGP World champ is turning his attention to his own promotion.

The first show for his Wild West Championship Wrestling is this Friday, November 3rd, at Castle Sports Club in Phoenix, Arizona. There are some good names on the show too — Horshu (Luther Reigns), Train (A-Train), Frankie Kazarian, Romeo Roseli, the Ballard Brothers, PUMA and Mike Barton (Bart Gunn), among others, plus Jonny Fairplay of Survivor fame.

It’s a bit of a trek for a guy from Atlanta, but Norton sees an opportunity in the west. “We’re not just doing this to do it, we’re doing this to try to make something — a good federation out west, because they don’t have one,” Norton told SLAM! Wrestling.

Norton doesn’t have roots out west — he’s a Minnesota boy — but he does have a bone to pick. He was hooked up with a promotion called Western Alliance Entertainment through Matt Bloom (A-Train), who does live out in Arizona. Norton was hired to be the talent coordinator and booker for the fledgling promotion. “He was working for another guy out here that kind of screwed him around,” explained Bill Anderson, Norton’s ring announcer.

The promoter in question was spending too much money and had unrealistic expectations, said Norton. Turning to the local wrestlers, Norton attempted to bring costs down. “I started saving him 60% than he was used to spending,” said Norton. “Something happened where he ended up booking a different show and canceling out all my guys. So I saw an opportunity out there and I wanted to make it right for the guys.”

The whole indy scene is a relatively new thing for Norton, who was blessed during his career to work mainly for the big guys. Growing up in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, he wasn’t a huge wrestling fan, but saw many guys he knew like Rick Rude, Curt Hennig and Wayne Bloom get involved in it. The 6-foot-3, 350-pound Norton, however, dedicated himself to arm wrestling, and would hold over 30 arm wrestling championships, including four U.S. National titles. He also appeared in Sylvester Stallone’s 1986 arm wrestling movie, Over The Top.

While on tour promoting the movie, he was approached by New Japan Pro Wrestling. “They talked to me, that they would like to have me be a wrestler. I had always known Rude, Hawk, Hennig, everybody,” Norton said. “I wasn’t comfortable with it, and I really didn’t want to do it. I knew it was there, I knew I could do it. But it wasn’t my first love. A lot of guys grow up and they want to play in the NFL, they want to do other things.”

He was schooled by former Olympic-wrestler-turned-pro Brad Rheingans, and a promotion to the AWA quickly followed in 1988. “They told me I needed to get on TV, to learn how to work in front of the cameras. So I went to the AWA. Verne [Gagne] actually plucked me out of camp early, which didn’t help me a bit.”

Scott Norton

Dubbed “Flash” for his penchant for winning matches quickly, Norton never really got too far in the dying promotion. “When I started in the AWA, I was serious about it, but it was almost to a point where Verne would put you in a position where you never felt like you were getting anywhere,” said Norton. “He was pretty good with the veteran guys. You were such a rookie in the business, I don’t know, I think it would take five years before he would accept anything that you did.” Baron von Raschke took him under his wing, and that helped immensely.

WCW came calling, but Gagne blocked the move and Norton was dispatched to Pacific Northwest Wrestling in Oregon. He was there about eight months, and held the PNW heavyweight title. “That was a good little territory. That territory was awesome,” raved Norton. “Every once in a while you made some pretty decent money, but you weren’t going there to make a living. You were going there to learn how to make a living.” From veterans like Len “The Grappler” Denton, Norton learned how to do interviews and how to survive on the road.

A match of his from Portland made its way to Japan, where New Japan realized that their project — almost forgotten in America — was ready for the big time. In Japan, he worked a lot of tag team matches to start, and won the IWGP tag titles with Tony Halme, and later with Hercules Hernandez as the Jurassic Powers. “We didn’t do a lot of interviews. We did most of our stuff in the ring,” he said of his early days.

Being a team player was important in the Land of the Rising Sun. “New Japan, it didn’t matter who the lineup was, who was going over, who was doing what. We worked together as a group to have the best show that we could have. That’s why the company kept making money, kept making money. It didn’t go up and down a lot, until Inoki wanted to buy a *&%$# island or something,” Norton said.

On September 23, 1998, Norton beat Yuji Nagata in Yokohama, Japan to win the IWGP World Heavyweight Championship, and he was just the second American to win the belt, after Vader. Norton would hold it again in 2001, and Bob Sapp and Brock Lesnar are the only other Americans to have held it since.

Though he’s currently a freelancer, the door is still open for a return to New Japan. The latest contract he was offered just wasn’t what he wanted at the moment. Norton is proud of his loyalty to one company. “Staying in New Japan for almost 20 years, every big man that came into that territory while I was there, before I was there, and after I was there — no, not necessarily afterwards — all the top names, when it came time for them to do business, they moved on. Meaning, when it came time that their big push was over, they were so worried about getting beat or so worried about this, they went to another company. They bounced around. Vader, Steve Williams, Bam Bam Bigelow, just to name a few,” he said.

“I stayed with the same company, and I’ve got a history with that company. When it was time for me to do business, I made it look like they had to pull the ring truck into the ring and run me over with the damn thing. I was the hardest guy in the business to beat basically over there. It wasn’t always a case of me worrying about me. I was into helping guys, like [Hiroshi] Tanahashi over there. It was really important to me to get him over. When I walk into a room or a locker room, I don’t go, ‘Yeah, look at that guy over there, look at that guy over there. *&%$#, he’s big. This guy, he’s really over.’ I’m looking at it like, ‘Oh man, there’s a guy I can work with. I can do business with him.’ Very few guys, they don’t understand it that way. There are guys that do, but there’s more that don’t. That’s just part of the business. They’re so worried about the other guys instead of themselves for what they can achieve with this guy, it just doesn’t always pan out.”

Things not panning out certainly describes Norton’s time in WCW.

He arrived in 1995, and was put in a team with Ice Train as the team Fire & Ice. He had a program with Sting, teamed with Buff Bagwell as Vicious & Delicious, and was a member of the New World Order (one of the few to be prominent in both Japan and North America in the faction). But that Japan connection hindered his career, he admits. “In WCW, it was mostly blamed on Japan, because every time they started getting me ready for something, I was going back to Japan,” Norton said. “You can’t really blame anybody for it, because I was working two different territories basically at the same time … they never really gave me the chance to roll with it.”

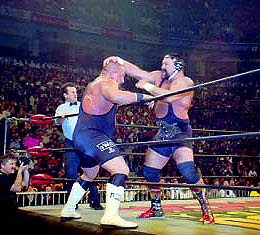

Rick Steiner takes Scott Norton to the pound during a WCW Nitro taping in Toronto, April 5, 1999. Photo by Stuart Green

Back when the NWO was hot, the NWO Sting was created, played by Jeff Farmer. The doppelganger praised Norton as “an unbelievable individual.”

“He’s very tenacious and strong-willed. The guy really has a determination that is unbelievable. You don’t get to the top of things that he’s accomplished in arm wrestling and in wrestling without that kind of determination. I think that’s one of those things that Scott really has,” Farmer said. “Some of it is stubborn, but it’s stubborn in a good way.”

When Farmer was first called to Japan to compete, Norton was able to help him with the differences in the ring action, and in culture. “He helped me make that transition. I’ve been indebted to him ever since. We’ve been friends ever since,” said Farmer. “We just hit it off. We had a lot in common, liked a lot of the same stuff. I’m not just saying this, but Scott’s one of the kindest guys in the business. He’s a guy who would take the shirt off his back and give it to you if you didn’t have one. That’s rare in our business, it really is.”

Like most wrestlers who were in featured positions in WCW during its late 1990s heyday, Norton can only shake his head at the insanity of it all. He would be shown booking sheets at the beginning of a day, and by the time the show was taped, everything on the card had changed. “Trying to keep everybody happy in WCW was impossible,” he said. “I was even offered one time if I would do the finishes, and just tell them. I said, ‘You can’t put me in that position with these people. It’s not my job.’ If you have to threaten somebody to tell them to do something, you’ve already lost control, control’s over with. That’s what it came down to.”

Norton just wasn’t one to play games. WCW was a compliment to his New Japan gig, not the end all, be all for him. “To make it big there, you had to be the biggest asshole on the planet. Literally, you really did. … Kevin Nash, he said it best, he didn’t get in the business to make friends, he got in it to make money. He said that a number of times. That’s pretty much the way you had to think about it. Everybody did make good money. We were being paid well. It was great.”

With all the lessons he’s learned, Norton is eager to give promoting a real try. He thinks that he’s put together a good team, including Anderson as ring announcer, C.C. Starr as his commissioner, as well as the cream of the western indy talent. “I’m behind him, whatever he wants to do. I said I’d help him in any way, shape or form. Give him some advice on indy talent that I know in the area,” said local resident Anderson. “I don’t doubt Scott’s intentions at all. That much I told him.”

Farmer has high hopes for his friend, though he has no plans of coming back to wrestling himself. “We need more promoters like Scott Norton, if he is going to get into promoting wrestling, because that’s the kind of guy you want — a guy that knows the business, knows the ins and outs, knows what it’s like to be one of the boys, and be involved in it,” he said. “There’s not a better ambassador for professional wrestling than Scott Norton … I’ve seen him bend over backwards for other guys who’ve come into the business, and helped them and guided them, and been like a mentor for a lot of these young wrestlers that come in. It’s nice to see that, he’s giving back to the business a little bit.”

“I’m pretty confident we can make this territory roll,” said Norton. “I run a locker room the proper way. I can’t tell you the number of times I was promised something in WCW, and the person who promised me something the next would see me and duck into a, he’d come out in the hall and act like he was reading something or avoiding me. I don’t do that. These who work with me, they’re going to find out real fast that if you’re not going to be honest with me, you’ve got a problem, because I’m going to be honest with you.”

If it all works out? “Maybe I won’t ever have to go back to work for New Japan as a job, do it as a hobby.”

RELATED LINK

- Sep 19, 2018: Winnipeg to benefit from Scott Norton’s lessons