In the 1950s, Doug Hepburn was one of the most famous Canadians in the world, renowned for his weightlifting feats. Yet, when thrust into the world of pro wrestling, he found that he hated it and dreaded each and every match.

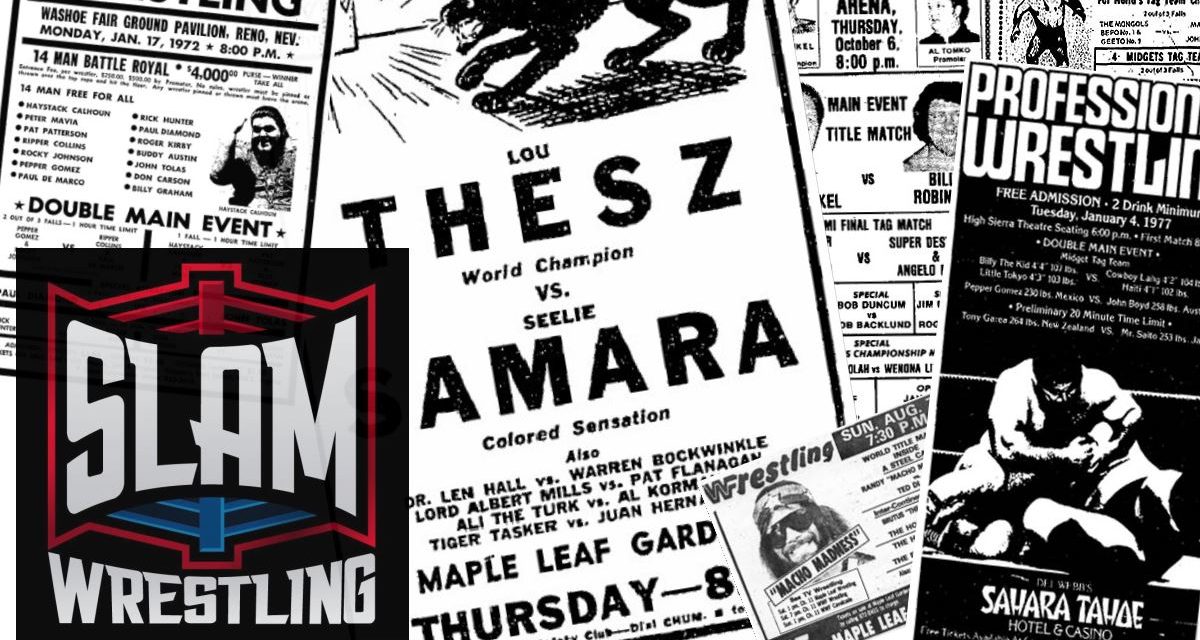

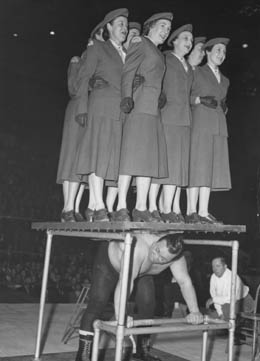

Doug Hepburn lifts Red Cross Girls during a demonstration in the wrestling ring in Toronto March 10, 1955.

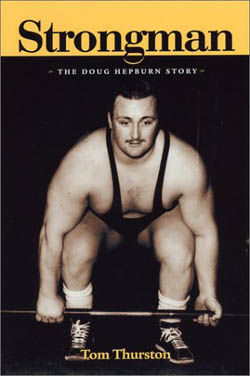

“[W]hat pained me the most about my matches was having to contend with the ‘violence for the sake of violence,’ both while training and performing,” Hepburn told his biographer Tom Thurston in Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story. “Hits, slams, bruises, dislocations and breaks were common occurrences that I abhorred — the giving, worse than the receiving.”

“He was just passing through in wrestling. He was a very nice, kind person,” Mad Dog Vachon explained to SLAM! Wrestling.

Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story is told in an unique, first-person narrative, where the author Thurston tried as best he could to capture was the man was really like. “He had such an unique way of expressing himself,” said Thurston. “He was almost like a W.C. Fields at times. He would sit down in a room and absolutely dominate it, just because of the way that he talked with a sense of humor. I thought to myself, I want to try to capture that. That was how I tried to do it with the first person [narrative].”

With such a colourful personality, wrestling would have seemed to have been a natural for Hepburn. “I think what the book was trying to do was show the extent to which Doug was disgusted with it. It just didn’t fit in. I guess disgusted isn’t the word. He just didn’t seem to fit,” said Thurston. “He had a good time. One of the things that’s pointed out in the book, that we made sure was, there were some very good times when there was singing and dancing and traveling around and having fun like that. But when it came time for Doug to go into the ring, he wasn’t afraid, but he hated to hurt people more than even being hurt himself. He just found it repulsive. He just did not want to be a part of causing pain to anyone. He was completely non-violent — and huge and strong.”

He was born Douglas Ivan Hepburn in Vancouver, B.C. on September 16, 1926 cross-eyed, and with a club foot. The eyes he would have fixed later, but a botched ankle fusion to fix his club foot resulted in a limp for the rest of his life. His early years were turbulent, with his parents divorcing when he was just three years old.

Hepburn began lifting weights as a teen, and upon dropping out of school, tried to find work that he could balance with his lifting. Having escaped the Second World War because of his foot, he set about becoming the strongest man in the world.

He would achieve his goal, becoming the 1953 World Weightlifting Champion in Stockholm. The win in Stockholm catapulted him into the media spotlight, after years trying to attract it.

San Francisco wresting promoter Joe Malcewicz approached Hepburn about wrestling, and flew him down to the Bay Area for a meeting.

In his memoir, Hepburn recalled the encounter: “I took off my shirt and his eyes bulged. ‘Get pictures!’ he shouted, all but shoving his photographer towards me. ‘We got us another Yukon Eric.'”

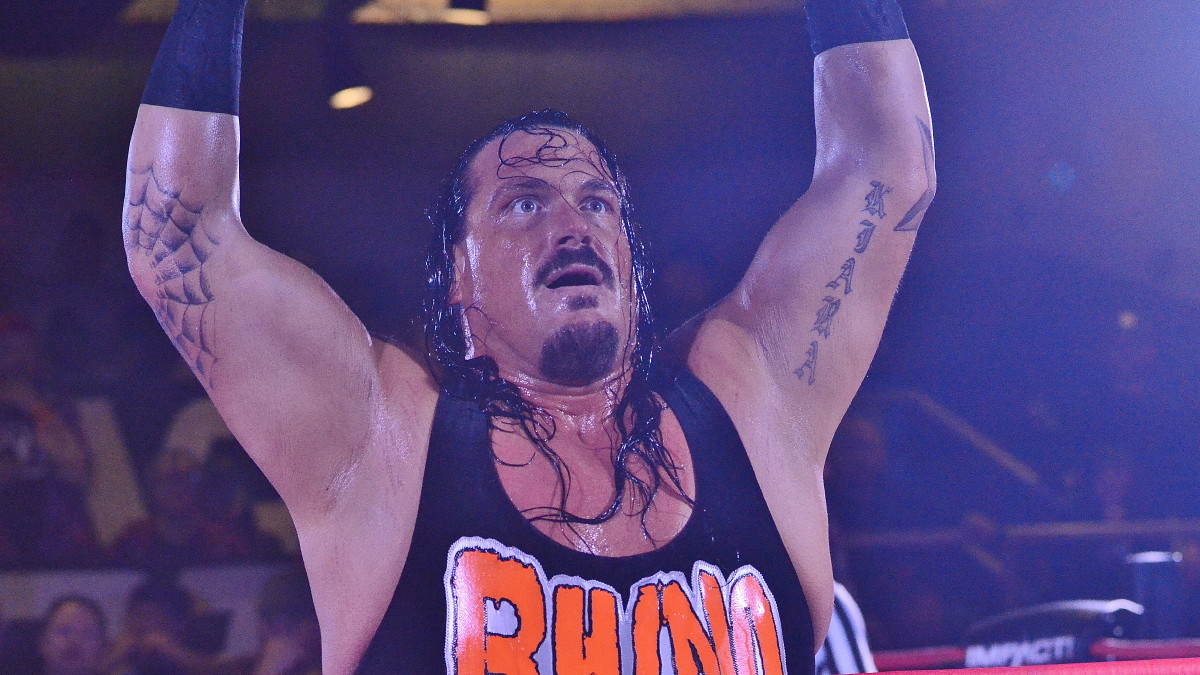

Doug Hepburn strikes his best Yukon Eric pose.

Hepburn was offered a deal by Malcewicz, but turned it down in order to concentrate on his preparations for the 1954 British Empire Games in his hometown of Vancouver. The city got behind him, and he was given $150 a week while training, and promised a gym by then-mayor Fred Hume.

At the British Empire Games, Hepburn would claim a weightlifting gold medal in the heavyweight division. He was a Canadian hero. One of his fans was a young Dewey Robertson, who would get into weightlifting himself before become a wrestle (and later the bizarre Missing Link). “I followed him quite a bit because I was into weightlifting myself. He was kind of an icon,” said Robertson.

Again, the wrestling business came calling. In September 1954, Whipper Billy Watson showed up, wanting him to enter the grappling game. Hepburn explained his dislike for violence, and they settled on a series of feats of strengths at the wrestling shows.

Hepburn performed at two to three shows a week across Canada, ripping license plates, crushing cans of oil, and lifting weights with his baby finger, as well as more traditional lifting: shoulder presses, squats, bench presses, two-handed curls.

Mad Dog Vachon was just starting his career in Northern Ontario when he first saw Hepburn perform. “He was the strongest man in the world, there’s no doubt in my mind,” Vachon said. “He used to do all these strongman stunts in the ring, between the semi-final and the main event, or whenever. He used to break rocks, bend steel bars, rip license plates.”

Breaking kayfabe, Vachon explained how some of the stunts were done. “He’d go backstage, and he’d ask the caretaker of the arena for a pair of pliers. You see those license plates, you can only tear them apart, there’s a rim around it. He had to cut them with a pair of pliers to start. There’s no way in the world you can do that without cutting the rim, like a wave. The bars, you know how they do the bars, to bend the bars? They cook them the day before in the oven. It makes the bar bend easy, because nobody in the world can bend a crowbar. He’d do things in front of the people. They didn’t care [that he’d fixed the stunts].”

Whipper Watson and Toronto promoter Frank Tunney sweetened the pot, and pitched Hepburn a wrestling contract that called for more money and more years. The Whip said to trust him.

“Although I had never met him before he had strode into my Vancouver gym, I had heard of him,” Hepburn said in his book. “He was as famous in the wrestling game as I was in the strength world, and well known for his ring antics and showmanship. Since he was also a rich and shrewd businessman, I knew that his promises were probably sound.”

He signed in January 1955. Tunney foresaw big things for him. “I think he has terrific wrestling possibilities,” Tunney said in a news story at the end of 1954. “Some fellows take years to develop in the ring, but he has a head start because of his tremendous strength. With that strength he doesn’t have to know all the holds in the world … All he has to do with wrestlers is lift them, drop them, then fall on them.”

Hepburn was trained in a basement gym at Maple Leaf Gardens with Watson and Pat Frayley. Hepburn learned the basics, and keyed on his finishing move, an inverted bear-hug.

“With my superior strength and lifting ability, wrestling should have been easy for me,” he wrote. “It wasn’t. While weightlifting, for the most part, is composed of well-balanced, straight-line pushing and pulling movements, wrestling is more to do with off-balance twisting and rolling movements. The skills that I was strong at and the skills that my wrestling opponents were strong at were often so at odds that it left me confused enough to scream. Add to this my less than enthusiastic desire to learn or be associated with the wrestling ‘game’ and I soon realized that my five-year stint would be a living hell – if I was lucky enough to remain alive for that long.”

Hepburn debuted March 22, 1955 at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, defeating Frank Marconi. He quickly moved up the cards, and was sent on the road with Frayley. “He hung quite a bit with Pat Frayley, and two opposites I’ve never ever heard of more than that. Pat was completely different,” said Thurston.

“The Canadian wrestling spotlight falls on Calgary Friday night as an order by officials of the Foothills Athletic Club creates a match of national importance,” crowed a Stampede Wrestling program for a July 8, 1955 show. “Doug Hepburn, holder of seven world’s weight lifting championships, and his manager, Pat Fraley, will go into the ring together against Fritz Von Erich and Lou Sjoberg. The bout is a direct outcome of last week’s riot that saw Von Erich disqualified against Hepburn because of interference by Sjoberg who rushed into the ring in a successful effort to prevent Hepburn putting his terrific ‘bear squeeze’ on Von Erich.”

In his book, Hepburn further expounds on his wrestling career — he made about $15,000 in 1955; enjoyed the attention of the women fans; and played a few ribs.

“Although the violence and exploitation wore away at me daily, not all my time spent as a travelling gladiator was bad,” he wrote. “For the most part, the wrestlers were a jovial, fun-loving group who shared a strong kinship and love to party during their off-hours.”

By his eighth month, Hepburn wanted out. He was depressed and turned to alcohol for solace. He began missing matches, and developed a terrible attitude. His opponents started fighting back with cheap shots, furthering his conviction to quit.

He wrote about the immediate reaction to his decision. “Opening the morning paper during a breakfast of scrambled eggs and toast, I found the ‘whole story’ of my quitting wrestling told by reporters who had no idea what the whole story was: Hepburn the brooder; Hepburn the quitter; but not a word about Hepburn the sincere athlete who hated violence and only wanted to help people.”

Writer George Dulmage quoted Tunney after Hepburn’s decision: “He’s a slightly mixed-up young man … A bit of a boy who acts first and thinks later.”

In 1959, Doug Hepburn would be talked into one more short stint as a wrestler in British Columbia by Cliff Parker (“a flashy Vancouver wrestling promoter”). Again, it didn’t last.

Following his wrestling years, Hepburn continued to battle alcoholism, but fought back onto his feet and opened a gym. He became an advocate of drug-free athletics, and designed and built sports and fitness equipment. Hepburn would continue to weightlift, and set many records for his age group as he aged.

Then there’s his singing. He released an album in the 1960s, and It’s Christmas Time is a fairly well-known Christmas tune on the radio. “They had it in the stores in Vancouver for a while, and they were hoping it was going to catch on, but it sold a few and then didn’t,” said Thurston. “They still play it in Vancouver every Christmas, the radio stations, as a tribute I guess.”

He received many honors during his life: He was named BC Man of the Year in 1954, and received the Lou Marsh Memorial Trophy for Outstanding Canadian Athlete of the Year; he is a member of the Canadian Amateur Sports Hall of Fame, and the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame (inducted 1966) and the Canadian Hall of Fame.

Hepburn died November 22, 2000, of a perforated stomach ulcer. Fortunately, he shared the memories of his life with Tom Thurston.

“Thurston’s biography does justice to all aspects of Doug’s life, illuminating the fortitude with which he met his many challenges. A truly splendid biography with many black and white photographs,” trumpets the Ronsdale Press publicity for the book.

The author is grateful that Doug Hepburn’s story got told. “I would have felt devastated if I couldn’t find anybody to publish the book,” admitted Thurston. “I think I would have died. It’s a story that I wouldn’t have liked to have seen disappear.”

Visit Amazon.com

Order your copy of Strongman: The Doug Hepburn Story