“Big Daddy” Gene Lipscomb was a larger-than-life football player, a unique physical specimen, colorful and memorable, and completely suitable for a side career in pro wrestling. Yet, before he hardly got started, he was done wrestling, and then dead at the age of 31.

Born in Uniontown, Alabama on August 9, 1931, Lipscomb never knew his father, and moved to Detroit with his mother at the age of three. When he was 11, his mother was murdered in the ghetto where they lived and he moved in with his maternal grandparents, where things weren’t much better. He worked from a young age, paying room and board to live with his grandparents.

Big Daddy Lipscomb. Photo courtesy The SPORT Collection

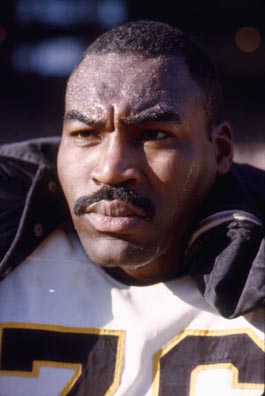

A star football player at Miller High School in Detroit, Lipscomb didn’t go to college. Instead, he was discovered by the Los Angeles Rams while in a Marine Corps camp in California. At 6-foot-6, 300 pounds, he was a monster for his day, suiting up as a defensive tackle for the Rams (1953-1955), Baltimore Colts (1956-1960) and Pittsburgh Steelers (1961-1962).

He dominated football games the way few defensive players ever had. He did receive his share of honors too, including the Dan McGuire Award as the Pro Bowl’s best lineman in both 1960 and 1963; he was on two Colts championship teams as well. Former Steelers head coach Buddy Parker had high praise for Lipscomb: “The best man I ever saw at knocking people down.”

Sports Illustrated‘s William Nack summed up Lipscomb’s impact on the game in a lengthy feature in January 1999. “He was, in fact, the prototype of the modern lineman, the first 300-pound Bunyan endowed not only with enormous power but also with the two qualities usually denied men of his size: agility and speed. His belly did not roll out of his pants. He was hard and trim, and the fastest interior lineman in the league.”

A long-lived quote from “Big Daddy”– he got the nickname because he used to call people he couldn’t remember the name of “Little Daddy” — carries on his legacy, which came to an abrupt and controversial end on May 10, 1963. “I just wrap my arms around the whole backfield and peel ’em one by one until I get to the ball carrier. Him I keep.”

In a column on ESPN.com, Hunter S. Thompson on ESPN described Lipscomb: “Gene ‘Big Daddy’ Lipscomb was arguably the cruelest pass rusher in NFL history. He was a violent junkie who invented the dreaded roundhouse whack upside the head — directly on the ear-hole of his victim’s helmet — that often burst both eardrums of any hapless offensive linemen he could reach. Big Daddy weighed 300 pounds and he really wanted to hurt people. And he did — but he is not in the Hall of Fame.”

Sounds like the perfect fit for professional wrestling, no?

Yet, generally in the ring, he wanted to portray a hero.

In June 1961, SPORT Magazine devoted a four-page photo essay with a short article to Big Daddy Lipscomb’s wrestling sideline. “Big Daddy-King of the Football Wrestlers” proclaimed the headline, surrounded by Lawrence Schiller photos of Lipscomb relaxing watching TV, getting a suit custom made, arriving at the arena, getting ready to wrestle, and in the ring.

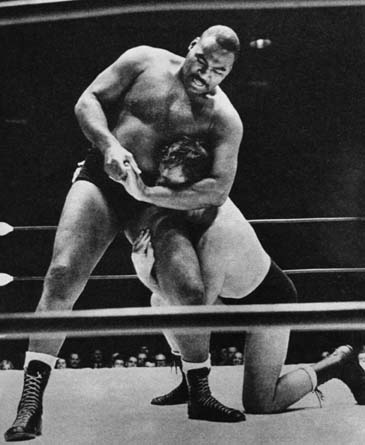

“Big Daddy” Lipscomb in action. Photo by Lawrence Schiller, courtesy The SPORT Collection

The gist of the SPORT article is that Big Daddy was going out of his way to be a “good guy” in the ring, as opposed to his vicious on-the-field reputation. “Nobody,” he explained, “is going to say that Big Daddy is a mean man.”

“Even when an opponent gouges and kicks, and the fans holler for revenge, Big Daddy won’t be drawn out of his clean-fighting shell,” describes the article.

The other impression that the writer of the SPORT piece took away was that Lipscomb was a quiet, respectful man in the wrestling locker room, where he was still a relative neophyte. In the football locker room, he is a joker and a “great kidder.”

Lipscomb entered wrestling initially inspired, at least in part, by the successes of football greats Leo Nomellini and Verne Gagne. (He would team with both on occasion during his brief career.) But his wrestling career never really amounted to much, no more than a part-time gig in the off-seasons of 1959-60 and 1960-61.

Yet, to him, it served a purpose. “I am in wrestling because I think it is good for football players,” he told writer-photographer Earle Yetter in 1961. “If I wrestle three or four nights a week during the off-season, I will not have much trouble getting down to my proper weight for the new season, because by wrestling I have kept an edge on my physical condition.”

In the SPORT article, he praised the conditioning of pro wrestlers, describing how much harder it was to go out seven nights a week for combat rather than once a week in football. Yet, there is little doubt that Lipscomb got BIGGER during his off-season spent in the ring. After a hot night of wrestling, he was known to drink a case of pop. Legend has it that his breakfast generally was a dozen eggs, a pound of bacon and a bottle of whiskey.

“Big Daddy” made the rounds more as an attraction rather than just a regular homesteader in a territory. Records show he was everywhere from Toronto to Columbus, Ohio, to Minneapolis, to Hawaii, to Los Angeles.

On the Wrestling Classic newsboard, Lou Thesz once offered up a comment on Lipscomb. “I never wrestled him, but I trained with him. Joe Malciweicz told him he could wrestle, but he lied to him. He was a great football player and natural athlete, but really liked the night life.”

“Big Daddy Lipscomb drank, screwed and dominated football games,” said his Steelers teammate, defensive back Brady Keys, on one occasion.

Married three times, Big Daddy had an insatiable appetite for women. One Rams teammate told Sports Illustrated that Lipscomb had a particular thing for hotel maids.

On May 10, 1963, all the merriment came to an end. After a night of drinking and partying with two women, Big Daddy collapsed in a kitchen in Baltimore. He had overdosed on heroin. According to the Sports Illustrated profile, the city’s assistant medical examiner, Dr. Rudiger Breitenecker, found enough dope inside him to have killed five men. Lipscomb died in the ambulance bearing him to Lutheran Hospital.

Lipscomb is buried at in Michigan at Lincoln Memorial Park, Macomb County (near Mt. Clemens).