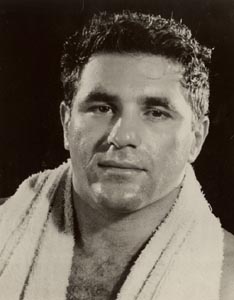

REAL NAME: Jack Laskin

BORN: March 13, 1929 in Hamilton, Ontario

6’0″, 205-215 pounds

ALIASES/NICKNAMES: Johnny Leroy, Abe Levinsky, Matt Burns, Peter Wickenoff

Growing up in Hamilton, Jack Laskin was a “sickly kid”, who weighed 148 pounds at six-foot, and was always getting colds, and always getting sick. Hardly the type of teen that turns into a successful pro wrestler.

But at 19 years of age, he made a decision. “I said I was going to join the YMCA and make a man of myself,” Laskin explained to SLAM! Wrestling in Las Vegas at the annual Cauliflower Alley Club reunion, where Laskin was being honoured. He bought himself some clothing and workout equipment and set off to change his life. “It took a great lot of courage to join by myself.”

Jack Laskin

Laskin arrived at the YMCA gym in August, and it seemed deserted. There was no one to instruct him on proper weight-training or diet, so he went to leave. As fate would have it, he passed the amateur wrestling room and found a young man doing exercises in there by himself. Laskin joined him, and they worked out together. “I turned on to it. I really liked it.”

His new mentor, named Elgie, helped him with diet as well as training. “Within a year, I gained 50 pounds and was feeling good, not sniffling and my skin cleared up.”

Thoughts turned to the pro game. “I loved watching the wrestling matches in Hamilton,” Laskin said, explaining that he went on a regular basis with his dad to the shows.

The pro wrestlers would come down to the YMCA about 2 p.m. to work out, and the group of amateurs there were in awe of the bigger men. One of the pros, Martin Hutzley, convinced Laskin to join Al Spittles gym, where everybody who was anybody in Hamilton pro wrestling worked out.

Spittles Gym was a converted two-car garage with weights and a wrestling mat. Laskin recalled that the old mat would come out at 7 p.m. for everyone to work out on. “Hudson Bay rules … get down and kill yourself!”

The gym left quite a bit to be desired. “It was a horrible place. You had to be dedicated to want to go to Spittles.” It wasn’t insulated, and had a wood stove to try to keep the entire garage / gym warm. “It should have been condemned a long time ago.”

As Abe Levinsky

Eventually the gym was condemned and Spittles opened a new location in the Westdale part of Hamilton. The filthy, hard mat went along for the move. “I never realized how hard that mat was until I had been away for a while wrestling professional when I came back,” Laskin said.

It was Hutzley that convinced him to turn pro. Contemporary rookies of Laskin in 1952 included John Foti, Skull Murphy, Tiger Joe Tomasso and Billy Red Lyons.

Joe Maich ran the “bullsh*t circuit” around southern Ontario, hitting towns like Smithville, Welland, Brantford, Simcoe and Ancaster. Laskin went as a fill-in one night as a favour to Hutzley, never expecting to stay. Maich renamed him Johnny Leroy for his match, which confounded the newcomer. “When they announced my name, I didn’t hear it, just stood in the corner,” he laughed. Laskin lost, but made $2 for the match. He remembers Maich saying, “great match kid. I’ll use you again.” True to his word, Maich booked Laskin regularly, and by the end of the summer the rookie was making $4 a match.

His new career in pro wrestling was kept secret from his family.

Laskin would get postcards from his fellow Hamiltonians around the world, yet he was frustrated because he couldn’t even get booked in the nearby cities like Toronto, Montreal or Hamilton.

Finally, he decided enough was enough: “I can’t stand this anymore. This is a way out of Hamilton.” Laskin didn’t know how to tell his mother that he was leaving, but once he did, she admitted that she had seen it coming. Laskin left Hamilton, starting in Detroit for Bert Ruby. He didn’t come home for three years.

Stints in Montreal, Texas, Nashville, Charlotte followed, while he continued to correspond with fellow wrestlers around the world. Wrestling served his “insatiable yearn to travel.”

Allen Garfield was a British wrestler from London who was wrestling in Toronto. He hooked Laskin up to go to England in 1956.

Laskin spent three years in Europe, and the London office would book wrestlers for Belgium, France, Austria, Yugoslavia, Spain and South Africa.

Europe was a different experience for Laskin, away from the comforts of home. He struggled with keeping his weight up. He went down to 185 pounds in England because the food was bad and there was “so little of it.” Plus, there was no place to go after a match, because all the pubs and restaurants would be closed.

Yet in Vienna, Laskin went up to 240 pounds. “It was a grand life. It was a tournament and we never had to leave [the city].”

The wrestlers would get up and have breakfast, then take a trolley to a park on the Danube where they’d work out with weights, swim, play games. Plus they’d bring along picnic lunches, drink beer and “gorge ourselves.” At five in the afternoon, they would head back to the hotel, then to the arena where they would wrestle, then go out for dinner after the matches.

After the three years in Europe, Laskin came home to visit, and planned to stay for a year. Once he got back on the road, he headed to San Francisco. “Hey, this will do,” he thought to himself, and cancelled an upcoming return tour of Europe.

He fell in love with the “continental atmosphere of San Francisco,” calling it “a magnificent city.”

Laskin bought a costume business in San Francisco and wrestled part-time. “I had made a decision to ease myself out of the business,” he explained. “I’d become a good pro, good at my craft, with good contacts.”

Yet Laskin wanted to avoid a permanent injury, and wanted to contribute more as a citizen — he didn’t want to be stereotyped as a wrestler.

Jack Laskin

In the early 1960s, the San Francisco territory was undergoing a change in promoters. Joe Meltsowitz was the promoter, and Laskin liked him. Roy Shires was slowing taking over the area, and Laskin had no time for him. “I immediately disliked him,” he said, adding that to him, Shires was “a boor, inconsiderate…[a] typical promoter.”

Two things were key to Laskin’s decision to end his wrestling career in February 1962.

Fellow Hamiltonian Jerry London (Jerry Aitken) was working in San Francisco, and had always struggled with his weight, never really getting much over 200 pounds. London was “not a great worker, just a plodder,” according to Laskin. After one match, Shires humiliated London in the dressing room in front of all the boys. That night London killed himself. “That saddened me a lot, but I didn’t know the details of it at the time.”

The other incident came in a match against The Destroyer (Dick Beyer) on television. Laskin’s timing was off, especially because he was only wrestling about once every two weeks. Nervous and quick to overcompensate, Laskin tried too hard to protect himself when he was launched into the ring corner. He took a bolt from the turnbuckle into his forehead, opening a big gash. The Destroyer was unsure what to do, but he knew it would look great on TV, and his white mask was quickly spotted with blood. After the match, Laskin needed stitches, but was faced with a drunk doctor at the arena. “I don’t need this now. Why am I here anymore?” he remembers asking himself. Pepper Gomez got Laskin home, and he didn’t hear from the promoter Shires until two weeks later when he wanted to book him again. Shires never said a word about the injury, which only reinforced what Laskin had said to himself the night it happened — I don’t need this anymore.

Laskin quit, and never looked back on a 10-year career, which he calls “an intense career, but not long.” The highlight of his career? Nothing specific. “The achievement, the accomplishment, the rest is the experience.”

After getting out of wrestling, Laskin’s costume business failed, and he became a Fuller Brush salesman — “the world’s strongest Fuller Brush salesman!” — which he did for 10 years. In 1972, he got involved in the burgeoning Silicon Valley and worked at a company that helped dentists arrange for patient billing. It was there that he met his future wife, Audrey, in 1976. He was her boss, and she was recently divorced. Laskin found himself over at Audrey’s for dinner and the relationship grew from there.

When the mid-’70s recession hit, his business changed because dentists couldn’t afford to do financing with patients as in the past, and he went into business with Audrey. Through his 70 dentist clients, Laskin lined up patients who needed loans, and became a de facto collection agency, with an office with just a desk and a telephone.

Audrey & Jack Laskin at the February 2001 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas. Photo by Rose Diamond

Laskin likes to joke about how his relationship with Audrey changed. “She asked for a raise and it was cheaper to marry her,” he said with a smile.

The couple sold the business in 1989, and retired to the country outside San Francisco. Laskin turned his attention to his Jewish faith and did community service. He found that many of the people he came in contact with wanted to get married, but the orthodox Jewish community wouldn’t approve of interfaith marriages. So Laskin got a license to marry people and became a lay rabbi. He is also the chaplain at Folsom State prison for the Jewish inmates, and serves at two hospitals as well.

“It’s a calling. That’s the easiest way to put it,” he said. “Wrestling to be me was a creative thing. … [now] it’s the spiritual side of myself that gets to express itself.”

Also on the creative side, Laskin has done a little acting in a local stage company, and wrote a play in 1999 called, One Of The Boys, a memoir on his life in wrestling. Laskin narrated the play while other actors performed his experiences with hat-pin wielding fans, bears and alligators, bad knees and anti-Semitism.

Like many wrestlers of the past, Laskin has a book coming out. But given his life in the heart of the computer revolution, he is doing an ‘e-book’, which is a “compilation of stories” rather than a tell-all book.

Laskin has a very good memory of all his experiences in pro wrestling, and that was the biggest impetus to writing the book. “How could I not write it?”

RELATED LINK