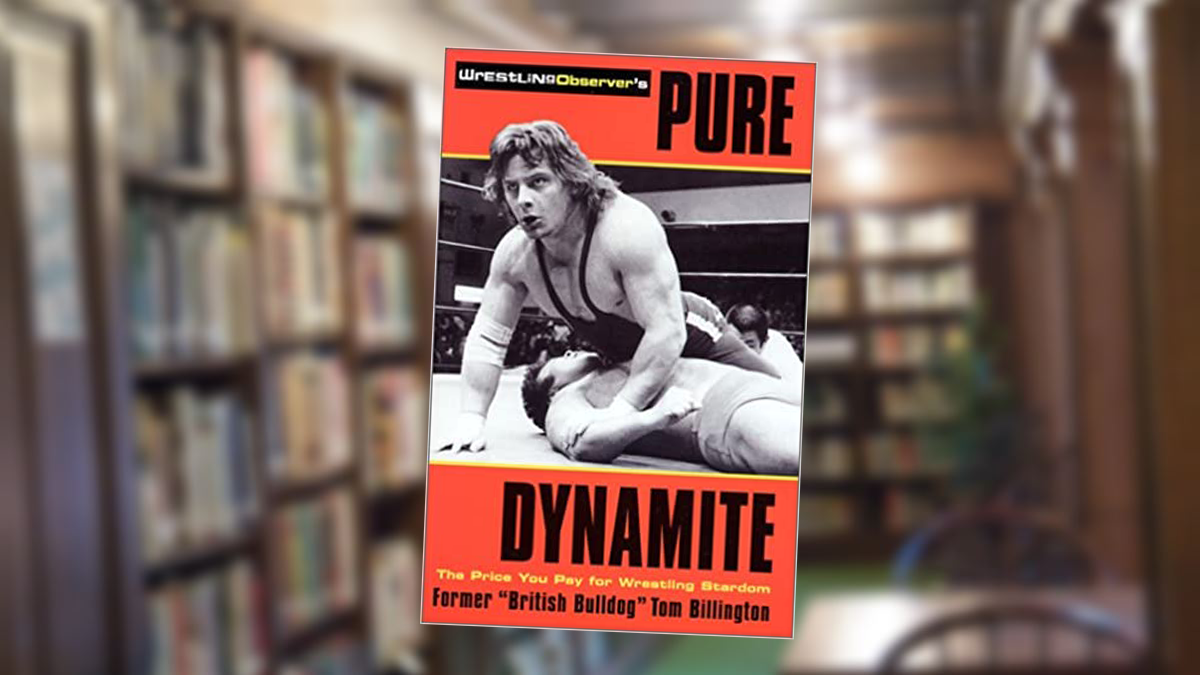

Dynamite Kid bio falls short

During his wrestling career The Dyanmite Kid was renowned for his stiff working style. A bit of a loner, his fellow wrestlers would often complain of his jaded, abrasive demeanour. He had few friends in the business and pulled no punches when dealing with people, be it other wrestlers or promoters.

How appropriate then that his book, Pure Dynamite: The Autobiography Of Tom “Dynamite Kid’ Billington, would be just as hard edged and broodish as the man himself.

Billington paints a brutal portrait of the wrestling business in the 1980s, recounting with great detail stories of life on the road. From his start in England, to his tenure in Stampede Wrestling, his time in Japan and his career during the height of the WWF’s popularity in the ’80s, Billington provides a historically and chronologically accurate record of his career.

Billington doesn’t sugar-coat anything, openly talking about his abuse of steroids and drugs. As a small, diminutive man in a big man’s business, Billington injected himself almost on a daily basis with steroids to gain much needed bulk. Living in the fast lane, he talks about spending money faster than he made it on drugs, alcohol and other distractions necessary to cope with the rigors of travelling on the road.

The book boasts several tales of hardships that Billington and his fellow wrestlers had to endure. Treated like chattel by promoters, Billington recalls countless stories of how promoters were always cheating him and other wrestlers.

The reader is bombarded by Billington’s frank and honest commentary, allowing them to peer beyond the glitzy surface of the wrestling business and to get a glimpse at its seedy, dark side.

Perhaps the most sobering story came in 1986 when he and Davey Boy Smith were WWF Tag team champs. After suffering a career threatening injury during a match in Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum, Vince McMahon called him up wanting him to work a TV taping in Florida so that they could get the titles off them and onto the Hart Foundation.

Against his better judgement Billington flew down to Florida, swallowed a handful of pain pills and worked the match. After the match, he was handed an envelope with his payoff for the night. Dynamite had risked his life to work the match and help out the company. And for his efforts, he was paid a paltry $25. That was the standard fee wrestlers got paid to work TV tapings. But Billington’s effort was anything but standard.

Aside from that harrowing tale, the book offers little more. He refuses to challenge the reader by analyzing his steroid and drug use, and instead offers story after story of the jokes he pulled during his career. Billington was a noted ribber and had a real panache for pulling pranks on other wrestlers.

Billington writes with great verve over how he relished pulling cruel and demeaning pranks on some underserving wrestler, as if to reaffirm some morbid sense of manhood he had.

And speaking of which, Billington makes sure the reader knows how tough he is to the point of nausea. He constantly reminds us he’s the toughest s.o.b in the business, how nobody ever dared crossing him up in the ring and how he never lost a fight in the locker room or in a bar. It gets tired and old real quick and makes it difficult for the reader to sympathize with the hardships he had to endure.

The book also offers little insight into his personal life. He barely touches on the strain the WWF’s grueling touring schedule had on the ending of his first marriage. Away from his home and family in Calgary almost all the time, Billington doesn’t share his feelings about being away from the people who loved him the most.

Equally curious is his questionable attempt at portraying his wrestling in Japan as real. Writing about his matches for New Japan and All Japan Pro Wrestling, Billington writes as if the matches were not predetermined, giving the reader the illusion that he won his matches because he was he was just tougher than his opponent. He inexplicably blurs the lines between what what was a shoot and what was a work in Japan, something he didn’t do when writing about his stay in the WWF.

The book is also marred by his continuous jabs and shots and cousin and tag partner Davey Boy Smith. Dynamite constantly reminds us that he was the one that got Davey Boy into Japan and Calgary and takes credit for his career. He considered him as a lap dog, always putting him in his place. We get it Dynamite, you made Davey Boy Smith into what he is today. He had nothing at all to do with it!

Billington does clear up the mystery over the source of bad feelings between the two. The bitter feelings stem from Davey Boy failing to tell Billington he was going back to the WWF, days before the Bulldogs were booked to work All Japan’s annual World League Tag Team Tournament in 1991. Billington called up Johnny Smith to fill his cousin’s spot and the two have been estranged ever since.

Billington also claims that Davey Boy ratted him out to his parents back home in jolly ol’ England about his steroid and drug abuse. As a result, Billington goes to great lengths to slag his cousin every chance he gets. Billngton seems to be trying to draw empathy from the reader over how his cousin “screwed him over” but manages the exact opposite. You end up feeling sorry for Billington as it’s obvious he’s a bitter man.

Billington is one of the most influential wrestlers of all time. Splitting his time between Calgary’s Stampede promotion and New Japan Pro Wrestling, Billington popularized a new style of pro wrestling, providing a blueprint for the junior heavyweight style wrestling match.

He was the archetypal junior heavyweight wrestler, a true pioneer whose influence can be seen directly in the work of such wrestlers as Owen Hart, Jushin “Thunder” Liger, and most notably Chris Benoit. His series of matches with the legendary Tiger Mask in Japan between 1981-83 were the precursor to Rey Misterio Jr versus Psicosis and Eddie Guerrero versus Dean Malenko matches that thrilled audiences in the 1990s.

It’s just a shame that his autobiography doesn’t match up to his legacy and legend.