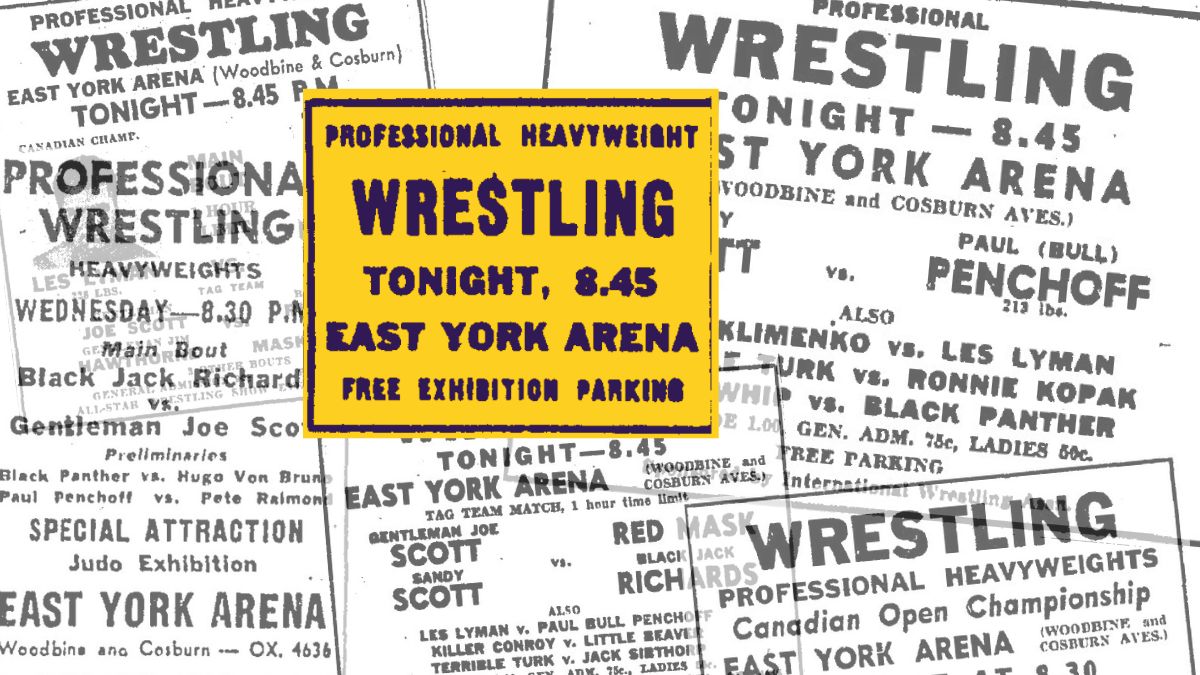

People always ask me why I love old wrestling so much. And no, not “old wrestling” like Dick Slater or Bob Armstrong – although I do love them both – but rather people like Bozo Brown, Farmer Marlin, and Red Berry.

After all, it’s a no-win proposition where you spend your free time (and income) trying to showcase your boutique wrestling knowledge, only to find out that Andy, 83, from Naperville, Illinois, can wax poetic about Verne Gagne, Wilbur Snyder, and all his other favorite stars from his childhood.

Don’t even get him started on Leo Nomellini; he can tell you his shoe size, favorite flavor pie, and what his mom called him when he was young – he was a fan club member. And you didn’t even solicit that information – he just happened to notice your Hulk Hogan T-shirt at the continental breakfast at Ramada Inn.

No, that’s not a real story, but you can use it in future screenplays.

But it demonstrates the futility – and fun – of the quest for knowledge. There is always someone smarter than you and someone who wants to learn. It’s an endless cycle, a treadmill of recurring payments to Newspapers.com and other archives, email chains, and tension headaches from screens and monitors. But that endless chase – that proverbial carrot at the end of the stick – keeps us going.

There are always loose threads to combine, faded legends to dust off (like Seelie Samara, likely the first Black claimant to the world’s title), and unlikely gimmicks to discover, which explains why I’m here today.

The “Sheik” gimmick is one we immediately link with hardcore wrestling and sadistic, ruthless foreign heels who will stop at nothing to conquer wrestling – including the nuclear option of hiring away the best grapplers in North America, including Roger Kirby and Jerry Blackwell.

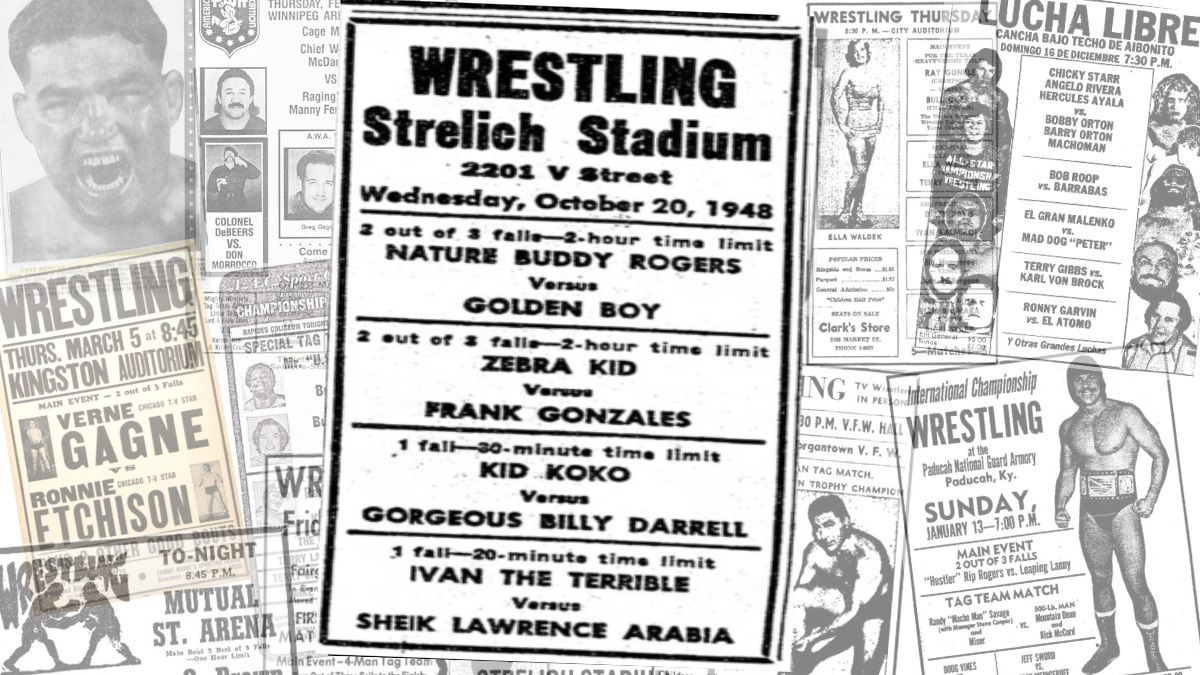

But it wasn’t always that way. In 1948 California, the name “Sheik” in wrestling meant honor, fair play, and handsome good looks. But more on that later – here is the card:

Wednesday, October 20, 1948

Strelich Stadium, Bakersfield, CA

- “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers d. Golden Boy, 2-falls-to-1

- Kid Koko vs. “Gorgeous” Billy Darnell, 30-minute time limit draw

- Zebra Kid d. Frank Gonzalez

- Ivan the Terrible vs. Sheik Lawrence of Arabia, 30-minute time limit draw

This evening’s card comes to us from the former Strelich Stadium, a 15,000-square-foot structure at 2201 V Street that was part dome, part barn, and, as a whole, a critical part of Bakersfield, California’s sports and entertainment history. It might have stank of stale beer and peanuts, but its 1,500 seats were a hot commodity for local fans, taking in boxing, wrestling, concerts with names like Roy Rogers, and comedians like Red Foxx.

But while stage shows were popular, the main draw to the building was the physical drama that played out in the venue’s ring. In fact, the stadium was built – and named – with combat in mind, named as it was for its original promoter and later owner, Steve Strelich.

Strelich, a Croatian-born California stuntman and professional swimmer, wrestler, and boxer, made a name for himself locally as “The Terrible Swede” and “Cyclone Steve.” So popular was Strelich that local property developer Henry Eissler told him that he would build him a stadium – but only if Strelich managed the building and called upon his numerous contacts to fill out the building’s schedule.

“The Terrible Swede” immediately agreed, and in 1940, the venue opened as Strelich Stadium, later Strongbow Stadium, and finally The Bakersfield Dome (often shortened to “The Dome”). The building was a key part of the local war bond drives during the Second World War, raising millions for the government – before shifting its charitable uses towards the March of Dimes in later years.

The main event of the evening features a very handsome struggle between virtue and vice, pitting the arrogant Buddy Rogers against the gallant Golden Boy, Jimmy Geoghegan.

There’s been so much written about Buddy Rogers that it almost seems ad nauseam at this point. Plus, anything I write would just be stepping on the toes of the great Tim Hornbaker and his excellent biography on the man, Master of the Ring. That said, I will briefly touch on how critical the Nature Boy was to his manager, Jack Pfefer.

By late 1948, the wrestling landscape had changed forever. The territorial system of the National Wrestling Alliance was in its infancy but had already started its expansion across the country. A process that began with the likes of Al Haft and Paul Bowser was now spreading, with large tracts of the American continent being carved up by aggressive promoters.

In this system, the might of the NWA came from its ability to pool resources, icing out the previously dominant syndicates and their barnstorming ways. And that process was deadly for people like Pfefer.

His wrestling promotions were based on the old big top circuses and thrived in the pre-territorial days thanks to his aggressive promotions, cut-throat business practices, and barnstorming sensibilities from his years with the Russian Grand Operas Company. But with the rise of territories and later alliances, he was edged out.

Rogers gave him the leverage to operate in the era of the NWA and helped him keep his seat at wrestling’s top table.

Wrestlers like Karol Krauser, the Swedish Angel, Dave Levin and Zebra Kid were great attractions and proved popular draws for Pfefer, but they weren’t cut of the same cloth as Rogers, who, even as early as 1946, was proving to be a sensational draw. With Rogers, Pfefer had a world-class, main event talent – and he knew it.

Hanging on to Rogers and keeping him happy by partnering him with his long-time friend Billy Darnell on the road was Pfefer’s ticket back to the big time, and he would milk it for everything he was worth. And it was Pfefer’s success with Rogers that not only helped him survive in the new era but thrive. It gave him access to valuable management roles in Southern California, Ohio, Colorado, and elsewhere and helped him book his huge roster across the United States – using Rogers, Darnell, and his other stars as the lure.

Rogers’ opponent on this evening was a popular Irish grappler named James Geoghegan. Geoghegan also worked under several other names, including as the chiropractor, Dr. Tim Geoghegan, Bob O’Shocker, and his moniker here: Golden Boy.

Geoghegan was a former circus strongman and won his fair share of female fans thanks to his muscular physique and Irish good looks. His run as Golden Boy saw him play the virtuous hero to the Nature Boy’s arrogant heel, with the two embattled in a bitter feud over the preceding months. Just a month earlier, Rogers had stolen a win from Golden Boy, flooring him with a fist when the referee wasn’t looking.

The semi-windup of the evening featured Rogers’ favorite opponent and long-time travel partner, “Gorgeous” Billy Darnell. He’s another name with so much written about him it would be treading water, so I’ll point you towards this great Steve Johnson piece: Billy Darnell Was a Consummate Fan Favorite.

Kid Koko was George Wilos, a longtime wrestler who worked under several names, including Rec O’Malley, Red Ryan, and “Hopalong Rocco,” though maybe not the “Jumpin’ Rococo” who was a notorious Antonino Rocca knockoff of the same era.

Wilos was another Pfefer world champion, beating a very veteran Dave Levin in 1950 and losing it later to one of Pfefer’s greatest gimmicks, the Elephant Boy, with his Slave Girl Moolah, at some point in 1951.

Speaking of Zebra Kid, here he is on this card. And, even better, it’s the original man under the hood – George Bollas! Bollas was a former Ohio State football star who transitioned to the physicality of wrestling without a problem but struggled to find his niche in a sport geared toward marketing. However, that changed when Bollas hooked up with Pfefer, a man known for creating some of the best (and worst) gimmicks in wrestling history.

As the masked “Zebra Kid,” Bollas found his feet as a tough rule breaker, but the name was always odd. Officially, he was called that because of his zebra print mask (and occasionally, trunks or cape), but if Frankie Cain is to be believed, it was something less glamorous than that.

According to Cain, who would find fame as the masked Mephisto in the 1960s and ’70s, was the errand boy and gopher for Pfefer and Rogers in their Toledo, Ohio, days and gave an entirely different meaning to the term “Zebra Kid.” As Cain retold it, the name came not from the zebra stripes on Bollas’ mask but rather the stretch marks on his body. Make of that what you will.

The Kid’s opponent was Frank Gonzalez. Gonzalez is billed as the “Champion of Mexico,” but I cannot find much out there. He’s an occasional name in the California area in the 1940s, appearing on cards with other Pfefer names like Frank Hickey and the usual Californian fare like Jules Strongbow.

I hope to learn more about Gonzalez, but the first bout of the night really drew me to this card.

The opening event was a Pfefer special, with gimmick vs. gimmick. Our first combatant is the rough-and-ready “Ivan the Terrible,” a vicious heel more accustomed to Moscow, Idaho, than Moscow, Russia. In this iteration, the character was really Don Lee, a 15-year veteran at this point who had worked under several monikers, including the “Masked Atom,” “The Scorpion,” a “Golden Terror,” and under his real name as “Cowboy” Don Lee or “Daffy” Don Lee.

Perhaps the most intriguing name on this card is that of “Sheik Lawrence of Arabia.” When you see that name – Sheik Lawrence of Arabia – I bet you are assuming that this is either an early appearance by or a low-rent knock-off of the “Original Sheik,” Ed Farhat. Sorry – wrong. Stop being so impulsive, sheesh.

Anyway, no. Ed Farhat was the Sheik of Araby, while our guy is Sheik Lawrence. So, what is the story of this guy? I wish I knew more, but let’s give it a shot.

The first entry of Sheik Lawrence of Arabia into the historical record is in Montreal in late 1946 as Sheik Abed (sometimes spelled “Abid”). Billed as “Assyrian by birth,” the so-called “novice grappler” was also sometimes stylized as “Champion of Syria,” which apparently wasn’t paradoxical to the Canadian press but built up a strong reputation not as a rule-breaker, but rather a popular, handsome, fan favorite.

According to the backstory, the Sheik served in the British forces during the Second World War and learned wrestling from American troops. Despite his lack of knowledge, he soon advanced and was a pro shortly after the war in Africa, Europe, and South America before making his debut in Montreal. His strength was his speed, though the press (and ladies) clearly felt it was his muscular frame and handsome visage.

The Ottawa Citizen was quick to note the novelty of the young grappler, writing on November 12, 1946, that “Arabs have long been noted for their abilities as gymnasts, but Abid, as far is known, is the first of his race to turn pro on the mat.” Apparently, he first approached promoter Eddie Quinn about wrestling with a traditional Arab beard, but the matchmaker told him to shave. It was a momentous decision as it propelled Abid (later Lawrence) to fame and gave the ladies a new heartthrob to cheer.

Regardless of the cause, his popularity quickly soared, and by the time of our card, he had adopted the Sheik Lawrence of Arabia name (sometimes styled “His Royal Highness” or HRH) and was already an established name in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and down into Texas and California. North of the border, he found his greatest support in Eastern Ontario, namely Ottawa and Quebec. His fame would continue afterward, too, peaking around 1951 when he became one of the most prominent faces on television wrestling from the West Coast, with press agents hailing him the second-biggest star in wrestling.

So, who is this mystery man who found fame as an Arab hero in a sport that’s determined that Middle Easterners are evil, bloodthirsty, and dangerous? I wish I knew, but there isn’t enough out there to say. Given his backstory and the start of his career, it is fairly clear he was a veteran, and given his start in Montreal with Eddie Quinn, he might have been a Canadian citizen or, failing that, a British subject of some other extraction.

It’s extra frustrating because his career is so bright but short. He appears suddenly in late 1946, gains traction around 1948/49, and is seemingly all over Californian ads in the early 1950s. He even won the Pfefer version of the World Heavyweight championship not long after this card, defeating the much-forgotten Jack O’Brien, the “Bloody Demon of Death Valley” and possibly one of the most successful professional wrestlers of all-time (if he is one and the same as Jack O’Brien of EMLL fame – I think he is) in February of 1949 before dropping it to Buddy Rogers a few months later.

But by 1953, Sheik Lawrence vanished without a trace, with very few mentions in the proceeding 70 years that passed. He may be the same man as another Pfefer “Sheik” – Sheik Ben Ali, who also worked as Emir Badui, Sheik Badui, Prince Emir, and Prince Emir JoJo, but it’s a strange, sudden departure from a successful gimmick in Hollywood to the mid-card act of Emir Badui in Bowling Green, Kentucky, Memphis, Tennessee, and western Ohio of 1955/56.

He’s an intriguing thread that needs to be pulled and one with a story to tell – but I guess that’s for another day. Still, it’s fascinating that the four decades that followed the disappearance of Sheik Abid/Lawrence were dominated by a Syrian menace in the Sheik of Araby, but it was at the beginning of his rise that he had another Syrian Sheik to combat – a force of good.

It’s a shame so much has been lost in wrestling’s television history, wiped and replaced repeatedly to save money at the cost of the sport’s past. It’s erased the legacy of names that might otherwise have endured – including Lawrence of Arabia.

But not all is lost – here’s our hero, Sheik Lawrence of Arabia, as he takes on “Crybaby” Bob Corby at Legion Stadium in Hollywood, CA, in early 1952:

Studying wrestling history will never bring you fame, fortune, or anything else of a particularly quantifiable nature. But it can help you dust off some famous faces and forgotten gimmicks – and show the world that Arab and wrestling weren’t always synonymous with nefarious ne’er-do-well.

And that’s enough to get me excited about my next project.

RELATED LINK