Professional wrestling fans are a weird bunch. I know since I’m one of them. We are loyal to a fault to our favorite form of entertainment despite its inherent absurdity.

Recently, I posted one of my columns to a broader online forum, hoping to get a few more eyes on it. It’s dedicated to true crime and supernatural silliness, where at least one host is an avowed wrestling fan. It’s a broader audience, but one that I figured to be partly sympathetic.

But sure enough, no sooner had I posted the link to my article, another user felt the need to post that “wrestling is a fixed sporting event anyway.”

To be honest, I didn’t mind. I’m used to that criticism, and if you’re reading this column (or anything about wrestling on the internet) you probably take the fact that wrestling is about storytelling as a given. However, that commenter was quickly roasted by others on the board; her pointing out the obvious was a matter of great offence to many there, and to the broader internet wrestling community.

Of course it’s just a show.

Which brings me to Young Rock.

Now approaching its second season finale, Young Rock has been positively received by critics and casual fans alike. Anchored by Dwayne Johnson’s superhuman charisma and a solid cast of actors, it tells a fictionalized version of Johnson’s story. Some wrestling fans (like myself) appreciate that it opens the door to a version of the behind the scenes world of pro wrestling and brings in viewers who wouldn’t bother with Raw or Dynamite, but enjoy a well-crafted sitcom.

In this sense, Young Rock follows recent shows like Starz’s Heels (which is totally fictional), Netflix’s G.L.O.W. and CTV’s Learning the Ropes (a truly deep cut starring the late Lyle Alzado as a high school principal by day/NWA bad guy by night; it’s horrible in the best way).

What I find fascinating, in the worst way, is how some fans have reacted to Young Rock, pointing out how episodes diverge from actual pro wrestling history, or how some actors differ from the wrestlers they play.

I have to admit, the last point occasionally takes me out of the show as well. Details like the number of stars on “Macho Man” Randy Savage’s trunks are occasionally enough to distract me, but constant harping about these non-issues feels like wrestling fans are looking a gift horse in the mouth.

Kevin Makely as Randy Savage on Young Rock. NBC photo

Pro wrestling, especially online, has become its own sub-culture, populated by self-appointed experts who insist on their own version of the facts — really, opinions dressed up as facts. Complaining about a show because it doesn’t “get things right” when it opens our hobby up to a mainstream audience just feels wrong; it’s the same behavior as the poster who was compelled to tell me that “wrestling isn’t real”, and deserves the same kind of response.

As noted, Young Rock is not a documentary. It’s not even a weekly wrestling show. It’s a semi-biographical sitcom, and while it draws inspiration from real-life events, those events need to be massaged in order to meet the 22-24 minute running time of each episode and capture a few different timelines. If anything, a multi-season sitcom gives the writers more breathing room to tell their story; imagine condensing all of this into a 90-minute movie instead of the roughly seven hours of content we’ve gotten so far.

Young Rock isn’t just bound by time constraints, but by the conventions of the genre. It’s meant to play to a broad audience, who care less about how buff the Iron Sheik should be than they do about their next belly laugh. The larger than life nature of pro wrestling translates well to this format, but the idea is to keep it relatable, light and entertaining.

One complaint that I’ve heard deals with The Rock’s relationship with his father, Rocky Johnson. On screen, it’s generally depicted as wholesome, leaving out Johnson’s infidelity (including the fact that his relationship with The Rock’s mother began while Johnson was married and had a whole other family in Canada; or the fact that the Rock’s grandfather, High Chief Peter Maivia was allegedly aware of how Johnson treated his daughter, but said nothing since he was up to the same sort of thing).

The Rock has been open that this relationship was at times challenging, and as a 50-year-old man he has every right to process that as he sees fit, in his own time, and to exercise whatever agency over it he needs to in the sitcom he produces. Simply put, while he’s made himself exceptionally available, beyond what he chooses to present to the public, his actual personal life is none of our business.

Past a point, it’s ironic that pro wrestling fans get irate over accuracy. Pro wrestling is built on suspension of disbelief, sometimes beyond reason.

For decades, the biggest title in the sport — the NWA World Heavyweight championship — claimed a pedigree that went back to the beginning of the 20th century. In fact, it was the product of collusion between promoters in the 1940s.

Within wrestling companies, promoters (especially active wrestlers) have sought to distance themselves from the operational side of things by introducing whole fake boards of directors and figurehead presidents. Some, like Toronto’s Jack Tunney, maintained a constant presence on our screen, even while real WWF owner Vince McMahon slaved away on commentary). Others, like the AWA’s Stanley Blackburn, were made up of whole cloth and never seen.

Wrestling promoters staged fictitious tournaments to introduce new champions. The WWE’s Intercontinental Title was allegedly first won by Pat Patterson in Rio de Janeiro. Titles have changed hands in phantom switches.

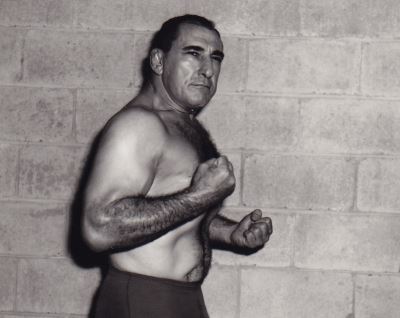

Argentina Rocca. Photo by Tony Lanza

Whole swaths of promotions’ histories are routinely retconned in and out of existence. When in the McMahon’s good graces, the list of best wrestlers ever begins with Shawn Michaels and ends with The Undertaker (depending on what Hulk Hogan’s been doing on Twitter). Bruno Sammartino, champion for 11 years, was ignored until rejoining the fold late in his life. Same goes for Hogan and Bret Hart and the Ultimate Warrior during their estrangement. Argentina Rocca, who headlined Madison Square Garden for years before Sammartino, is never acknowledged.

Performers have left promotions and come back under new names and nationalities and masked identities, sometimes winking at their audience’s willingness to believe (see Hulk Hogan as Mr. America, Andre the Giant as the Giant Machine, or Dusty Rhodes as the Midnight Rider for starters).

“I’m not Hulk Hogan, Brother!”

One of the fun things about professional wrestling is its loose relationship with facts, including its own history, so it’s tough to see fans offended by what they see as mischaracterizations and inaccuracies in a business built on deceiving the public. Young Rock can’t be blamed for its willingness to play fast and loose with what is already a dodgy historical record. Complaints of this nature are a step or two away from “you know this is fake, right?” Boo on that.

I admit, I like Young Rock. I’m all for anything that helps bring pro wrestling to a broader audience, and that lays bare the conventions of the genre, so people like that commenter don’t feel like they’re blowing the lid off of a giant secret when they point out that wrestling is staged. As entertainment, Young Rock is no less staged and we should take our own advice.

Just enjoy the show.

TOP PHOTO: The WWF locker room, as portrayed on Young Rock, when Dwayne Johnson had his WWF debut in Corpus Christi, Texas. NBC photo

RELATED LINKS