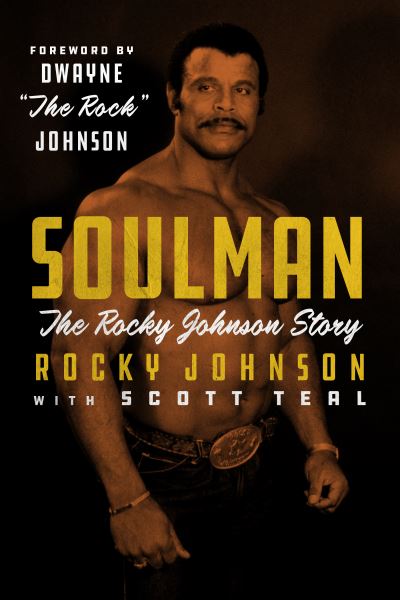

Rocky Johnson says he “wanted to tell the good, the bad and the ugly” in his first book, Soulman: The Rocky Johnson Story, out October 15 from ECW Press.

While the ahem younger crowd may know Johnson primarily as the father of former wrestler/topper of the 2019 Forbes’ list of the highest paid actors in the world, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, the more seasoned wrestling fans will recall the career of the man who came first. A man with one of the best, if not the best, dropkicks in pro wrestling ever and a career that spanned over two decades. A man who claims to have “had more than 10,000 matches” and was the first African-American wrestler to win the Georgia, Florida, Texas, Southern and North American heavyweight titles, and in tag team competition, was the first black wrestler to hold the Georgia (with Jerry Brisco) and WWF (the World Wrestling Federation, now known as World Wrestling Entertainment or WWE, with Tony Atlas) tag team titles.”

Rocky Johnson. Photo courtesy ECW Press

Johnson was born Wayde Douglas Bowles and originally hailed from Amherst, Nova Scotia. (Yep he’s from Canada!) He legally changed his name to Rocky Johnson, as a tribute to boxers Rocky Marciano and Jack Johnson, in 1986. At the age of 14, Johnson found himself homeless after a violent altercation with his mother’s alcoholic boyfriend. He decided to move to Toronto to live with one of his older brothers. (Undoubtedly, this is part of “the bad and the ugly” aspects of his story that Johnson forewarned.)

“I packed my clothes in a cardboard suitcase and hitchhiked the 1,600 miles to Toronto with just two dollars in my pocket,” wrote the 75-year-old Johnson in the book’s second chapter. “I had a sore throat, my nose was running, and it was unbearably cold. I had holes in the bottom of one of my shoes, so I had put a piece of cardboard inside.”

He continued, “During the four days it took to reach Toronto, I slept in fields, barns and under bridges. I ate apples I stole from orchards. To be honest, I didn’t know how to get to Toronto, but I knew it was southwest of Amherst.”

Johnson says it was a month before he found his brothers as he didn’t know their addresses in Toronto. He got a job at a car wash to support himself and in his meager amounts of spare time, he would work out and train at the Trinity Community Recreation Centre. Johnson initially had dreams of becoming a boxer until Mother Nature changed his fate.

“I was picking up boxing, amateur boxing,” recalled Johnson, who currently resides in Lutz, Florida, in a phone interview with SLAM! Wrestling. “The wrestlers used to train there too; they had a separate ring. So, I’d be boxing, hitting a punching bag and I kept watching the wrestlers. But then one night it was real cold and snowy and nobody showed up. But I was there!”

He went on, “So I’m there hitting the bag and one wrestler (Rocky Bollie) showed up and there was nobody there for him to train with. So, I got to talking to him and he said, ‘Hey come in and I’ll show you a couple moves.’ I said, ‘Okay, but don’t hurt me.’ He said, ‘I’m not gonna hurt you.’ So anyway, he showed me a couple holds, but he was just using me as a sparring partner, but I didn’t know the difference.”

Intrigued by pro wrestling, Johnson asked Bollie how to get into the sport. Bollie told him about a wrestling school in Hamilton run by Jack Wentworth. With Bollie’s assistance, Johnson was accepted into the school. With his job at the car wash only paying $1/hour, Johnson could not afford his own vehicle for transportation. He says he would take a bus “twice a week for $2.40 each way” to the wrestling school. After two months of training, Johnson had his first match.

Johnson provides plenty of details on his wrestling journey as he hits the mats throughout the many pro wrestling territories and shines a light on their cast of characters. But just like his beginnings, he says that his journey was a struggle particularly because of his race. There were many walls that he had to break down for himself and future pro wrestlers of colour. And Johnson says that letting the public know about these struggles was one of his main motivations for writing the book.

“I had a lot of difficulties,” he remembered. “When I first started in this business there were only, like, three black wrestlers. There I am a young kid, cocky, sassy, pretty good shape and they weren’t giving me the big push. Even when I became champion in the South and I became the first black Tennessee Southern heavyweight champion, I would go get a (hotel) room and they would say they didn’t have any rooms. A white wrestler would come by and they would get a room. I was sleeping in my van and stuff like that. But I never got mad. I never got discouraged.”

He added, “They (the readers/the public) don’t know what I went through in the ’60s, when I went through all the racial prejudice and rode up and down these roads and had to take a bus to these towns and get a $25 pay off and stuff like that. But I never gave up. I want the people to know what it’s like. No matter what, you can achieve anything if you put your mind to it.”

In addition, Johnson says he experienced horrific and racist name calling and some wrestlers even tried to injure him on purpose. He was also incensed when he witnessed some of his fellow black wrestlers being treated “like garbage” and being forced to portray offensive and demeaning characters.

“I worked hard on wrestling moves, and I was in the gym every day — either in Hamilton or at the rec center in Toronto — because I wanted to show the world that I was a professional athlete, and not the stereotypical ‘Stepin Fetchit’ black wrestler,” he passionately wrote in the book’s sixth chapter. “Throughout my career, I told promoters that I came in as an athlete, and I was going to leave as an athlete. Most blacks followed the other scenario: doing the jive talk and eating watermelon and fried chicken. That wasn’t me.”

But while the book is a compelling read and Johnson has moments of candor, for example he surprisingly admits that he was one of many wrestlers who had extramarital affairs on the road, the book does come off as quite guarded. This reader can’t help but feel this book is very much on the surface and presents only what Johnson wants to project to the public.

And while I learned a lot about Johnson as a wrestler, I felt deprived when it came to who Johnson is as a man. To me, Johnson let his guard down more during his 2008 WWE Hall of Fame induction speech and our phone interview. I wish that side of him, that emotional investment, had been captured more in the book. (Johnson worked with writer Scott Teal on this book.)

It must also be pointed out that while Johnson reveals he is on his third marriage and shows a lot of character by only having kind words for all three of these women in the book, his only child mentioned by name is Dwayne. (Dwayne’s mother is Johnson’s second wife, Ata Johnson. Ata is also the daughter of the late High Chief Peter Maivia.)

At the time of the interview, Johnson said he had not yet seen the book and seemed genuinely shocked that his older children, Curtis and Wanda from his first marriage, were not named in the book. He also alluded to having issues with Teal.

In response to this reader asking about this omission, the publisher stated in an email: “Rocky’s children are mentioned in the book, but not by name in order to respect their privacy. They also aren’t involved in wrestling which might explain why they were featured less prominently.” But whatever the reason might be, and whatever is truly going on behind the scenes of this book project, the omission is quite glaring, uncomfortable and off-putting especially with Dwayne writing the book’s foreword, being mentioned in the book’s acknowledgements and even garnering his own chapter. Johnson’s other children aren’t identified by name or even gender in the book.

Despite those misgivings, this reader still feels Soulman: The Rocky Johnson Story is an essential and inspiring addition to her bookshelf. We could all learn a lot from Johnson.

“I want to let them (the readers) know that ABC: anybody can, if they want to,” concluded Johnson. “Not only in wrestling, not only in sports, but in anything. I want to show them the hardship that I went through. I started out at 14 years old training! I just want them to know! And it doesn’t have to be wrestling. Wrestling is what I know so that’s what I wrote about. But when I do lectures and stuff like that, I let them know that you can do it! It’s all psychological. It’s all in your mind. I can! And that’s what I want to leave behind. I want to leave something behind for my kids, my grandkids, 100 years from now when I’m gone.”

RELATED LINK