When he was 14 years old, Mickie Henson was the president of the Bobby Heenan Fan Club. Little did he know that he would later become friends with Heenan, and enter into professional wrestling as a referee — a profession at which he excelled, and for which he is being honoured for by the Cauliflower Alley Club.

Henson will be presented with the Charlie Smith Referee Award at the CAC reunion in Las Vegas April 30-May 2, at the Gold Coast Hotel & Casino.

“It’s quite an honour,” said Henson, who actually learned about the impending award at Bobby Heenan’s funeral. “It’s nice to be recognized, that’s for sure.”

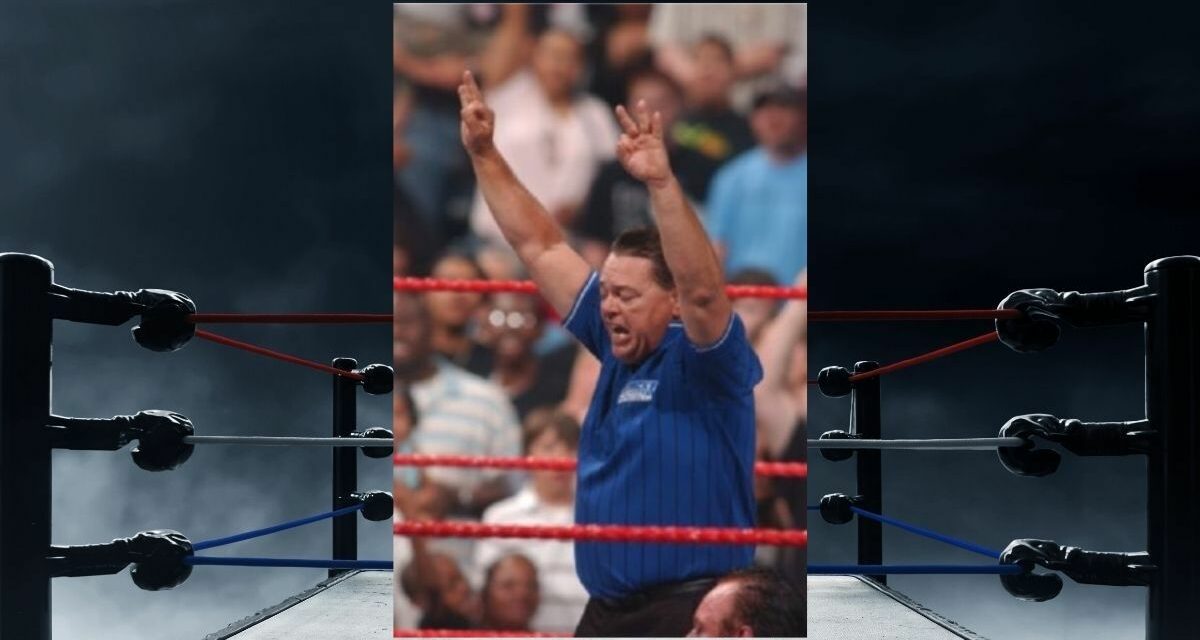

Mickie Henson as a WWE Smackdown referee.

Given the many health issues that Henson has faced since cancer knocked him for a loop in 2008, and forced him out of his WWE refereeing gig, Henson has even more reason to celebrate with his friends in Las Vegas — including fellow honouree Steve Keirn, who was the man who actually got Henson into the business.

Henson’s story starts on May 1, 1961, in Rock Island, Illinois. He fell for pro wrestling via his grandfather, who was a big fan, and took him to the matches in Moline, Ill., and the summer shows at the ballpark in Davenport, Iowa.

Hitting the age of 16 meant that he could drive. “I would always go to the airport and meet the little private AWA that would land,” recalled Henson. “I always tried to get the heels to give ’em a ride to the show, because that would get me in for free. Then, of course, they’d always stop to buy beer afterwards, and they’d give me a six-pack of beer. Being 16 years old, that was a big plus.”

The AWA took a hiatus from running Moline, and the next time it was in town, Henson saw two newcomers, Stan Lane and Steve Keirn.

A young Mickie Henson and Bobby Heenan.

“I was standing there and there were these two blond guys who I’d never really heard of or seen before, the Fabulous Ones. I’m, like, well alright. Long story short, I gave them a ride. That’s how I first met Steve. We became pretty good friends.”

Keirn remembers Henson’s enthusiasm for the business. “Mick was a good kid, he was a nice kid. He was really up to date on wrestling,” said Keirn. It was often Henson driving Keirn, Lane and a young Curt Hennig around.

The snowy AWA was not for Keirn, and he and Lane were heading back to Memphis, and then Florida. Before he left, he told Henson he’d call him when he got to Florida and he should come for a visit and try to figure out the whole pro wrestlig thing.

Henson took a two-week vacation from his job. “I think I stayed four days, changed my ticket, flew back home, quit my job, packed my car, and I’ve been in Florida ever since,” said Henson, who calls Key West home.

Henson started refereeing on Professional Wrestling in Florida (PWF) cards that Keirn promoted along with Mike Graham and Gordon Solie. “I was using guys like Mike Awesome that I’d taught, all these guys that I was teaching, we were just supplying the show with characters, so they got broken in pretty quick,” said Keirn. “Mick became a referee, and boom, his thing was history from there.”

“I was thrown right into the fire, so to speak, with no experience,” laughed Henson. “I learned as I went. I was fortunate enough to learn from guys like Steve and Mike Graham and Dick Slater, some of the old-style guys that really knew how to work back in the day. I slowly progressed and refereed with Steve. When Dusty [Rhodes] came in and worked as part of the office, I worked for Dusty.”

The idea of PWF was to fill the void left when Jim Crockett Promotions bought Florida Championship Wrestling. But the landscape changed, and WWE and WCW soon became national promotions, and regional territories became a thing of the past.

So Henson went back to Key West, not really thinking he’d ever work full-time in pro wrestling again. But he never forgot his friends, so made a fateful eight-hour trip up to Tampa for a WCW TV taping to see some of them.

In the hotel bar that night, WCW referee “Pee Wee” Randy Anderson, prompted by Kevin Sullivan, asked Henson if he wanted a tryout as ref. Of course, he replied. He was then instructed to get a blue shirt, a black bow tie, black pants, and black shoes.

And one more thing.

“At the time, I had hair almost down past my shoulders, living the young, dumb style life,” chuckled Henson. Anderson asked him, “How fond are you of your hair?” The next morning, Henson got it cut, and headed to Bradenton, a little town just south of Tampa Bay, for a WCW Saturday Night taping.

“I was nervous in trying to remember everything I was supposed to remember,” said Henson, who was assigned two matches. “I remember getting ready to just go out the entrance and Pee Wee grabs me and he says, ‘Hey, if we needed to take you to San Francisco this weekend for the pay-per-view, could you go?’ I went, ‘Waa, waa, wwha, yeah!’ ‘Okay, you’re on! Go!’ And they pushed me out the curtain. Of course, as soon as I walked out, I forgot everything that I was I thinking about finish-wise for the two matches. I was like, holy crap.”

The match he was out there for wasn’t, in fact, one that he’d been assigned; he mentioned it to the ring announcer who just told him it was too late. “I figured I’d just call it the way I see it, and that’s what I did,” said Henson. The subsequent match was one he had been assigned, it went a little better.

When he came back through the curtain, was told he was going to go to San Fransciso. Henson went back to Key West to quit his job at a bar, but was told he was only being allowed a leave of absence — really, what kind of career was being pro wrestling referee?

In WCW he was known as referee Mickie Jay. “I was with WCW until it folded,” said Henson, referring to the April 2001 deal where WWE bought WCW.

Jerry Lee Lewis and referee Mickie Henson.

There were lots of good times in WCW. A long-time music fan, Henson got to meet some greats along the way, including Toby Keith, Jerry Lee Lewis, ZZ Top, and Lynyrd Skynyrd. His encounter wth “The Godfather of Soul” James Brown brings up some of the puzzling things about WCW.

“To me, in WCW, there were a lot of things that really didn’t make a lot of sense. Eric Bischoff, his idea was, ‘Well, we don’t want to tell anybody. We want it to be a big surprise,'” explained Henson. “For instance, they hired James Brown to be on the pay-per-view in San Francisco — they didn’t tell anybody, it was just a big surprise. ‘Hey, James Brown’s here.’ Well, to me, wouldn’t you advertise James Brown is going to be there?”

Mickie Henson and James Brown.

Then there’s actor David Arquette’s WCW World title win. “I was the lucky referee that got to raise his hand,” admitted Henson.

When WWE bought WCW in April 2001, it did not take on all of the contracts, picking and choosing those it wanted. Henson was not hired, and headed back to Key West, content to have his wrestling days behind him. But his friends looked out for him.

Roughly two years later, Keirn, then a WWE road agent, convinced the head of talent relations, John Laurinaitis, to give Henson a shot. But it came with a caveat: Henson had to lose weight. “I set out and started walking, and I mean walking,” recalled the 5-foot-7 Henson, who also changed his diet. “I lost almost 50 pounds in a month.”

Before his tryout, Henson met with Keirn. “When he saw me, his jaw dropped. He was like, ‘Wow. For somebody to say they’ve lost that much weight and then to really see somebody who’s done it, I couldn’t believe it,'” recalled Henson.

“The next thing I knew, they flew me from Key West to Dallas for a tryout. I think that’s pretty much unheard of for anybody to fly a referee anywhere for a tryout.” Dallas was Monday Night Raw, and Henson was given a dark match. Laurinaitis told him, “just do what you’ve always done, and Vince [McMahon] likes aggressive referees.”

It all came back to him pretty quickly. “I went out for the dark match and came back in and they actually put me on Monday Night Raw that night, so for my first tryout, I actually had a match that was on the TV show.”

As with WCW, things moved crazy fast from there. He was asked if he could work in Laredo the next night, and Henson agreed “having no idea how far away Laredo was from Dallas. I think I spent nine, 10 hours in the car trying to get there.” At the Smackdown taping, Henson met Vince McMahon for the first time, and was offered a contract; he refereed under his real name, lest anyone with poor eyesight confuse him with woman wrestler Mickie James.

Keirn said Henson was more than deserving of the job.

“He’d come from WCW so he had the experience and he was a great referee but it goes back to why he was — he was a great referee because he wasn’t just collecting a paycheque,” said Keirn. “He was a great referee because he loved what he did and he tried to give it his best. That’s what really makes talent and referees is having pride in what you do, and also the respect for the business, you care for it and you protect it.”

Henson was with WWE until September 2008, when he was diagnosed with Mantle cell lymphoma. “That’s where my career took an abrupt ending.” He was actually on WWE’s payroll until January 2009, when the company ended the idea of keeping Raw and Smackdown separate brands, and therefore downsized.

Steve Keirn and Mickie Henson with Bobby Heenan, not long before “The Brain” passed away.

As remarkable and unpredicted as his run in wrestling was, his perseverance in his fight with cancer tops it.

Initially, a doctor told him he had about six months to live, and to get his affairs in order. As bad as that was, the time at home was equally unsettling. “I went from 280-plus days on the road to doing absolutely nothing, boom, nothing. I was freaking out, really. I didn’t know what was going on,” he admitted.

A friend in Cleveland named Tony Bacho, who had battled prostate cancer, insisted he come north, both for treatment and for the company. They’d been friends from the famed Key West bar, Sloppy Joe’s, where Henson had worked.

Bacho “basically saved my life,” said Henson, thrilled that his buddy that he lived with for two and a half years will be in Vegas at the CAC reunion for the presentation of the award.

In the short version of his cancer fight, Bacho knew people at the Cleveland Clinic, and Henson was taken in even without insurance, and started his chemotherapy there. The cancer went into remission, then came back; repeat.

“I’ve been fighting it ever since,” said Henson, who now takes four pills a day instead of chemo, and is back living in Key West. He feels good, has a healthy appetite and is optimistic.

On full disability, he can’t referee any more, and is content helping a friend here and there with a catering business, and fishing. “My spare bedroom has a waiting list of people that want to come down,” he said.

The other thing in Florida, besides his trips to Moffitt Cancer Center Tampa, is his mother, institutionalized at age 90 with dementia. With no brothers or sisters, it has fallen to Henson to take care of her.

He’s happy to do it, as she was always supportive of his outside-the-norm job choice. She made six scrapbooks of her son’s wrestling days, “full of everything I did in my career, every magazine article, every story, every mention, is in these scrapbooks that she put together for me.”

The other family hasn’t left Henson either. He will occasionally go to the regular wrestler luncheons in Tampa, and when WrestleMania was in Orlando in 2017, Henson worked as “Tony Chimel’s gopher in the production office.” Hanging out backstage was like old times but “without the stress.”

RELATED LINKS