Most people would not put Antonino Argentina Rocca’s name at the top of their go-to list of professional wrestlers for consultation on hand-to-hand combat or self defense.

Looking back at pro wrestling’s early television era of the 1950s and 1960s, many performers earned stand-out reputations as tough and dangerous men in an already tough industry, and these reputations have carried on even after their deaths.

Several of them were not just tough but technically skilled, coming into the business with extensive backgrounds in combat sports or martial arts such as boxing, amateur wrestling, and judo. Some holdovers still possessed a solid working knowledge of the old art of professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling, giving them reputations as “shooters” who could disable or maim a man with tactics not permitted in the amateur ranks. A select few had even taken those skills and adapted them for use by the U.S. Armed Forces during the Second World War.

Antonino Rocca does not fall into any of these categories.

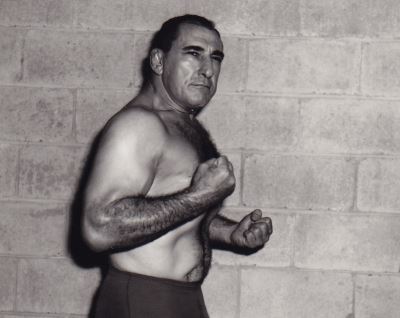

Among his peers, Rocca was certainly respected for his capacity to connect with the fans, especially those of Hispanic or Italian descent, but his abilities as a wrestler or fighter were never held in high regard. In 1960, Fred Bozic, who had been a good amateur boxer in Cleveland before turning to professional wrestling, stated, “I’ll bet I could pick out 25 rasslers today who could throw Antonino Rocca in a shooting match, and maybe more.” Multiple-time world’s heavyweight champion Lou Thesz was even less generous, singling him out for wrestling’s descent into “ridiculous comic-book characterizations,” while declaring that “Rocca became one of the two or three biggest names in professional wrestling during the 1950s, and he did it without a lick of wrestling ability.”

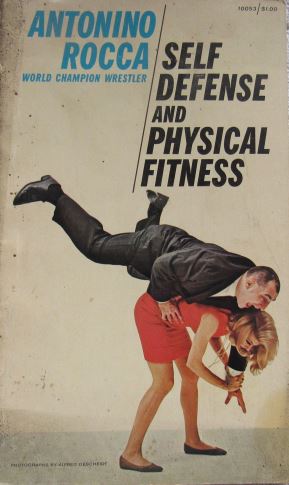

Born in Treviso, Italy, in 1921, Rocca emigrated to Argentina as a young man. He participated in several sports, among them soccer, swimming, and rugby, though the precise details of his achievements in each of these athletic disciplines remains murky. A master of spinning yarns for the purpose of self-promotion, Rocca inserted a number of fantastical achievements into his personal history, among them earning a degree in electrical engineering and winning the Carnegie Medal. Although once claiming to have defeated 18 Amazonian tribesmen in combat, little of either his confirmed or kayfabed past speaks to training in combative arts. It may therefore come as a surprise to some that, late in his career, Rocca penned a book devoted, at least in part, to self defense, entitled Self Defense and Physical Fitness.

A posed shot of Rocca by the great Montreal-based photographer Tony Lanza.

Rocca’s text, published in 1965, was by no means the first work on self defense written by a well-known professional wrestler. A half century earlier, Martin “Farmer” Burns’ mail order course Lessons in Wrestling and Physical Culture offered students, in his estimation, “the best of all self defense methods” for dealing with common unarmed and armed attacks.

Following Burns, mail order impresario Earle Liederman, with the help of middleweight wrestler Martin Ludecke, released the beautifully-photographed Science of Wrestling and Art of Jiu-Jitsu in 1923. In an attempt to capitalize on the mail order fitness craze while Ed Lewis claimed the world’s heavyweight title, Billy Sandow also included a book on self defense, modelled on an earlier book he had released in 1918, in his multi-volume 1926 Sandow-Lewis Library. Unlike Burns, Ludecke, or Sandow though, Rocca apparently lacked a training background that would lend itself to authoring an instruction manual on the subject.

With scant evidence of authorial expertise in the field, coupled with a proclivity for crafting tall tales, readers of Antonino Rocca’s Self Defense and Physical Fitness would be justifiably hesitant in picking up his work and hoping to get some solid, usable information from it. While it can confidently be stated that the long-out-of print book never became many people’s main go-to guide for the subject, it certainly has some merit. Self Defense and Physical Fitness offers more solid advice on training than it does the “ridiculous comic-book” methods which Rocca was criticized for employing elsewhere in his professional life.

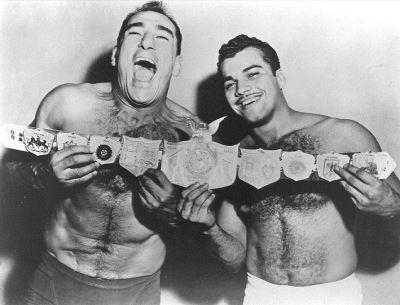

Argentina Rocca and Miguel Perez dominated the tag team scene in Capitol Wrestling, based in New York City. Photo from the collection of Bob Leonard.

At 75 pages, Rocca’s Self Defense and Physical Fitness is a slim tome. Furthermore, only a small portion of the work, totaling 16 pages, is devoted to self defense. To its credit, the book makes no claim to being an authoritative treatise on self-preservation from physical harm, but only “a selection of those tactics and maneuvers that will be most useful and practical to women as well as men if they are forced to defend themselves.”

A limited roster of “maneuvers” is not in itself a bad thing. Any good self defense program, at its heart, should be comprised of simple, adaptable methods that do not require fine motor skills or a complicated series of steps to master.

Rocca purports that the tactics presented in the book are a combination of wrestling, judo, jiu jitsu, savate, football, and soccer. In reality, the course offers very little in terms of foot fighting methods that might be derived from the latter three, a fact that may come as a surprise to some, given Rocca’s propensity for kicking and foot slapping during his in-ring performances. On the whole, his self defense program relies primarily on basic hip tosses and leg sweeps, intended to throw an adversary to the ground, in combination with a sprinkling of strikes. Once tossed to the floor, there are no suggestions on how to follow up.

Much in contrast to many other courses from the same time such as Bernard Cosneck’s American Combat Judo (1944, but reprinted in 1959) or the lesser-known Modern Self-Defense by R.H. Sigward (1958), Rocca altogether excludes not only immobilizing a grounded opponent, but also ground fighting, from his course. To this day there remains an ongoing debate over purposely engaging in ground fighting in a self-defense situation, with the Gracie Combatives program and various W.E. Fairbairn-inspired modern combatives systems representing different ends of the spectrum. This is not the place to enter into that discussion, but given the general criticism levied by Rocca’s peers against his actual wrestling ability, it is telling that the text remains silent on the issue.

Antonino Rocca had no reputation as a “tough guy” or even as a competent combat athlete among his peers, but that does not necessarily preclude knowledge on the subject of self defense. To that end, his work offers useful advice and some practical methods for dealing with an assailant.

Antonino Rocca had no reputation as a “tough guy” or even as a competent combat athlete among his peers, but that does not necessarily preclude knowledge on the subject of self defense. To that end, his work offers useful advice and some practical methods for dealing with an assailant.

As much as Rocca was often derided for his wrestling ability, nobody doubted his physical fitness. Not surprisingly, it is with respect to achieving this latter objective that the book really shines.

For a yarn spinner and over-the-top performer, Rocca presents a physical fitness program that is devoid of false promises and silliness. In contrast to the ad copy for an old Charles Atlas course, Rocca does not try to sell quick fixes, either. To the contrary, he states that achieving peak fitness can take several months, if not longer. In pursuit of that objective, Rocca offers a progressive exercise system of bodyweight exercises that can be done virtually anywhere. He begins the course with five “preparatory exercises” that could be performed by most novices. Like in David P. Willoughby’s Master Method of Health, Strength and Bodybuilding, which presents a similar, though more strenuous intro program, Rocca suggests continuing with these exercises on a daily basis once you have moved on to more advanced routines.

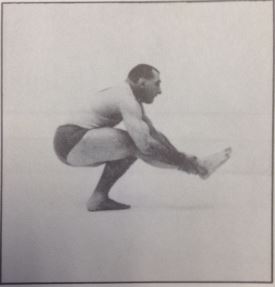

Following the preparatory exercises, Rocca offers a double progression program whereby students work on a series of movements until they have achieved a specified series of repetitions with them. With that done, they move on to the next set of exercises. The final challenge consists of exercises that are termed the “Rocca Special.” These exercises are challenging, and if someone can complete all five of them in sequence for 20-25 repetitions with good form, they will have achieved a solid level of physical fitness.

One thing included in Rocca’s program, but often missing from contemporary courses, is his series of neck exercises. He correctly states that “the neck is one of the most vital and least exercised parts of the body.” He stresses the value of neck training not only for athletes but as a preventative measure for common aches and injuries. Coming from the field of professional wrestling, it is not surprising that Rocca would put a priority on neck exercises, including the wrestler’s bridge. Today, controversy rages over the efficacy of the wrestler’s bridge for neck training, and even some of Rocca’s contemporaries, such as Billy Wicks, were dead set against it, while others, such as Lou Thesz and Karl Gotch, considered it a cornerstone of their training. Rocca, however, does not emphasize the high bridge commonly seen in Greco-Roman wrestling and, via Karl Gotch, practiced by most Japanese professional wrestlers. Instead, he uses the low bridge, similar to what Farmer Burns shows in his mail order course. There are only a couple of instances where Self Defense and Physical Fitness descends into the outlandish. For example, in dealing with multiple attackers, Rocca uses one opponent, who is attacking him from behind, as a flail to disable the other attacker. It is doubtful that either a tribe of angry Amazonians or a pair of urban muggers would fall for the trick.

On top of the exercise program itself, Rocca offers plenty of advice, the most valuable (and ignored) of which is to be scrupulously consistent in your effort. He rightly asserts that you should never give in to avoiding exercise if you do not feel like it. Rocca warns, “Stop even for a few days, and the setback will amaze you.” Very true.

On top of the exercise program itself, Rocca offers plenty of advice, the most valuable (and ignored) of which is to be scrupulously consistent in your effort. He rightly asserts that you should never give in to avoiding exercise if you do not feel like it. Rocca warns, “Stop even for a few days, and the setback will amaze you.” Very true.

Like any physical training program, results are only gained through earnest and consistent effort. Rocca’s system for physical fitness is more detailed than his program for self defense, but aside from his “Rocca Special Grand-Dad Exercise,” a push-up and shoulder pressing movement, bodyweight exercise aficionados won’t find much novel in his selection of exercises. Here too, though, hard work, not the acquisition of knowledge on obscure movements, is the key to success. Moreover, a high level of physical fitness, with a special emphasis on training the neck, will have the added benefit of preparing a person in the unfortunate event of a physical assault.

Antonino Rocca’s Self Defense and Physical Fitness is a long out of print text written by a professional wrestler whose esteem within the professional wrestling fraternity was never commensurate to his box office appeal. It is not an outstanding book but it is better than might be expected based upon the way that Rocca was often derided by his “tough guy” peers. More than that, it is one of the few treatises on physical training penned by a professional wrestler of his generation. Early pro wrestling pioneers such as Tom Cannon, Tom Connors, and George Hackenschmidt, in addition to those previously mentioned, all put their ideas on training into published texts. More recent pro wrestlers, most notably Triple H, have also done so. Those who reached their athletic peak between 1945 and 1970 were relatively silent on the subject. Fortunately, Karl Gotch’s contributions to physical training live on through the training programs used in Japanese wrestling dojos as well as instructional videos, and a recently released Japanese-language book. Other professionals who were esteemed for their commitment to physical fitness, such as Edouard Carpentier, Archie Gouldie, Reggie Parks, and Fred Atkins (whose approaches to training were previously chronicled by SLAM! Wrestling!), didn’t put their ideas on paper. Rocca did, and much of his advice remains useful today.

C. NATHAN HATTON is the author of the book Thrashing Seasons: Sporting Culture in Manitoba and the Genesis of Prairie Wrestling and has over 20 years of involvement in submission grappling, as well as training in karate, boxing and other martial arts. He has undertaken a close study of historical catch-as-catch-can wrestling and currently coaches and trains in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu at Leading Edge Gym in Thunder Bay, Ontario, where he holds a brown belt in the art. Hatton has a PhD in History and teaches at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario.