Iron Mike Award acceptance speech from the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion

On May 3, Tully Blanchard delivered an impassioned, heart-felt and moving speech as he accepted the Iron Mike Award at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas. Read what he had to say, and you’ll be moved too.

The setting was the Gold Coast Hotel & Casino, and the Wednesday night was the final night of the CAC reunion, with Blanchard in the main event spot.

Jim Ross, the emcee for the evening, talked about Blanchard: “Of all the wrestlers I’ve seen in 40-plus years, I never saw a more natural, athletic heel. He was an amazing heel. He proved that you don’t have to be a giant to get over if your work is fundamentally sound and if your psychology is on point. If you’re that good on the canvas, if you’re a grappling Rembrandt on your canvas, you can be very, very successful. There’s no doubt in my mind that our 2017 Iron Mike Award winner was at least a Rembrandt on his canvas.”

Ross then called upon JJ Dillon to introduce Blanchard, who he managed in Four Horsemen. Dillon recalled first meeting Blanchard in Amarillo, Texas, in 1974, when Tully was the quarterback for the West Texas State Buffalo. They wouldn’t meet up again until Jim Crockett Promotions. Dillon praised Blanchard for ability to succeed both as a singles and a tag team wrestler, and he reminded everyone that Tully never said “I quit” during his United States title loss in an I Quit Steel Cage match to Magnum T.A. at Starrcade ’85.

“I also had a chance to manage him later and he regained the title, but I’m not taking credit for that — he deserves all that credit,” said Dillon. “We have become extremely close as members of the Four Horsemen. It’s certainly the pinnacle of my career. It’s hard to explain to somebody that the genuine affection and camaraderie that exists between elite, Tully, Arn, the Naitch, and Barry Windham. There was a chemistry among that’s hard to describe to anybody else, and 25 years later, we’re still the best of friends, and it’s a friendship that will last a lifetime. He’s a Hall of Famer, he’s a Horseman, but for me, most of all, he’s my friend, Tully Blanchard.”

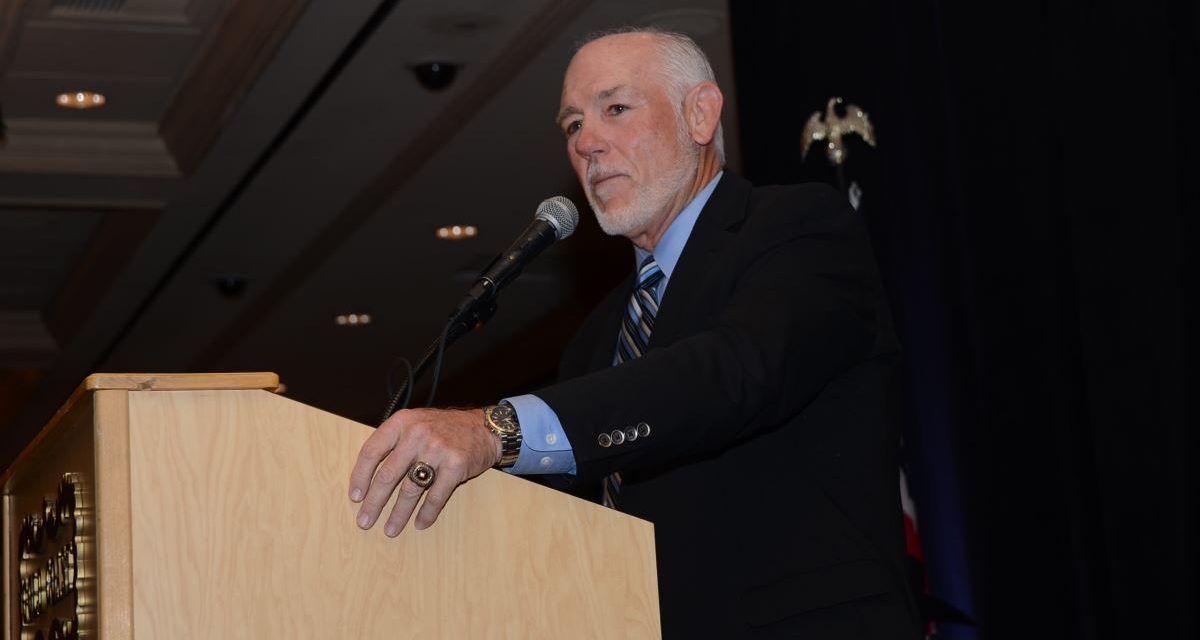

With that, Dillon ceded the stage to Blanchard, who spoke from the podium for 15 minutes with the ease of a professional speaker, his voice clear, rising and falling for emphasis. His message was even clearer.

Here’s an unedited transcript of Blanchard’s speech (which, as noted in the report from the event, his daughter Tessa watched via phone from Japan):

“Wow. Golly. Five minutes to nine. Oh, you’re chuckling. I used to be long-winded. The last time I stood in front of a group of people to talk about anything was in a prison someplace, and they were all dressed in the same outfits, and they didn’t want to be there. Some of you guys don’t want to be here right now because it’s been a long evening. Great food, great fellowship. I will be concise. I’ve only got four pages … not really.

“But, when I go the phone call that I was going to receive the Iron Mike Award at the Cauliflower Alley Club, my mind immediately shot back to when I was 10 years old and Iron Mike was in my kitchen, talking to my Dad. That was just amazing that this guy that was in a movie with John Wayne was in my kitchen.

“Then as you get older and you learn, the people that I got to meet and poured into my life — the Red Bastiens, the Nick Bockwinkels, but even more, Lou Thesz, [the] World champion used to stay at my house and teach me over breakfast as he cooked, over dinner as he made meatloaf, with stuffed cloves of garlic in it. And I listened and I listened and I listened and I listened.

“Because I’m not the biggest guy, and as Jim [Ross] alluded to, I had to be better than most because I was a promoter’s kid, and promoter’s kids didn’t actually get good treatment all the time. I worked and I worked, and my Dad quickly told me one thing; he said, ‘You know, it took Nick Bockwinkel 10 years to realize that he was not a good babyface, and to switch heel.’ He said, ‘We need to do that with you, because you’re not a good babyface.’ I said, ‘No.’ I switched heel, our business tripled, and Wahoo McDaniel taught me how to get heat, get beaten up, and sell tickets for two years, every night. ‘Hit me, beat me up, ship me in.’ Chop! Bam! People tell me, ‘That ain’t real.’ And I go [pointing to his chest], ‘Blood running down my chest? How much more real can you get?’

“And then the next season of my life was wrestling Buddy Roberts, who was wrestling as Dale Valentine because John had come to work for my Dad. To to go to the ring every night and back to the arena, and sit there and listen to John Valentine critique every move, every night. The knowledge that was going in. And that helped our business.

“But I would be remiss if I did not say to you what I consider the most important thing, to feed the knowledge in my ultimate success in this business was the three years that I refereed in the summer when I was in college. I refereed six matches a night. I refereed the opening match to the last match. As Kevin [Von Erich, via video] mentioned, the matches underneath that were guys just finishing their career or starting their career, but you were right there and you watched it, you listened to the crowd respond, and then you got to go to the ring with Jose Lothario and Mil Mascaras, and you want to see how it happened, and how they sold, and how the angles were, and you were in the middle of everything. And you learned the timing that was successful. And to do that in World championship matches, and hour Broadways, and [watching] Dory Funk for an hour. It was unbelievable how that vaulted my career.

“And then our business plummeted. Things happen. I went to North Carolina. North Carolina was down at that time, in 1984. Wahoo McDaniel switched heel; that made sense, but it worked. The first sellout we had in 1984 in the Greensboro Coliseum was Wahoo McDaniel and myself against Blackjack Mulligan and Ric Flair, and that started Dusty Rhodes’ reign in that territory. It was nothing, it was like running free horses after that. The people had got back, the people got excited about wrestling. And things were just unbelievable, every night, all over the country you were in a sellout. I cannot remember when it wasn’t a sellout some place, from the west coast to the east coast.

“Cable television was taking over. WCW was monster. USA Network and WWE was monster. And that’s what the wrestling business was going through in the ’80s.

“Arn [Anderson] and I met with Vince [McMahon] and decided we needed to go to the WWF at that time, at the end of 1988. Phenomenal experience to walk in Madison Square Garden. Phenomenal experience to walk in the Boston Garden — I was talking with somebody from Boston here this week; I was a huge Celtics fan growing up and to walk into the Garden when it’s empty and see the banners, golly.

“To work with Pat Patterson, and to get the knowledge from him, and the other agents, Tony [Garea], [Chief Jay] Strongbow, [Blackjack] Lanza. I’m 63 now, so I’m a little bit forgetful.

“But that part of my life was so much, we had fun every night. You got to go out and entertain people, and it was unbelievable. To go into the ring with Ricky Steamboat in the Greensboro Coliseum? Oh my gosh. Every time he moved his little finger 16,000 people screamed, and all you had to do was pull his tights, and blink twice. It was unbelievable, all you had to do was take bumps, just get beat up. And collect the cheque. It was phenomenal.

“But then life comes to making choices, because the Iron Mike Award is not just the wrestling business, but what you do outside the wrestling business.

“My career ended full time in 1989. I made a bad choice one night in Madison, Wisconsin, and the next morning I got to Philadelphia at a two o’clock show at the Spectrum and it said, ‘Piss test’ on the wall. Well, you can’t snort at four and be clean at two, just in case nobody in here knew that.

“I flunked a drug test that day. November 2, 1989, Vince called me on the telephone, we were in Rochester, Illinois, and asked me a question. I didn’t have an answer for him. He said, ‘What are you doing with your life?’ And I couldn’t answer him. I just kind of made some noise. He said, ‘Turn your airplane tickets in and go home.’ So I did.

“I’d negotiated a deal with WCW, Arn and I had a three-quarters of a million dollar contract set. I thought that was good, and they didn’t have a drug policy, so I really thought I was good.

“Everything was fine until November 13th, when Ric Flair called me at one o’clock in the morning and he said, ‘They found out about your drug test, and they’re not going to honour their contract.’

“At 35 years old, I went from World champion superstar to unemployed, and, ladies and gentlemen, I promise you, I did not handle that real well. A lot of times you might just throw stuff or whatever, I was so mad I couldn’t move. I laid in my bed and I was paralyzed, except my brain was going at light speed.

“And at 4:03 in the morning, I said five words that changed everything in my life. I said, ‘Jesus, take over my life.’ And it was the first time I’d ever used the name Jesus when I wasn’t cussing somebody. I wasn’t raised in church, that was not the way we did that stuff. I always thought church was for weak-minded people, that needed a crutch. Not us, especially the people in this business, because we manipulate people. When you walk out of the dressing room and you go in front of an audience of 18,000 and you get them to do what YOU want them to do, when YOU want it done, how can anything be any greater than you?

“And to think an impossible, an invisible god were actually possible. But instantaneously, when I said those five words there was a calmness that came over me.

“I have been telling people that story for 27 years, that there is a second chance. Just because you’re sitting in a prison yard, there is a second chance if you start walking a different path.

“It is not logical at 35 years old for me, where I was in this business, to just be gone. I’m not the only guy to ever flunk a drug test, am I Pat [Patterson]? Didn’t mean to put you on the spot.

“They all went back to work, they all sold tickets. They all performed. But every time I tried to get back into this business the door got slammed in my face. I never understood that for many years.

“I lost all the money that I’d saved. It was insanity.

“But God had put me on different path, and at 63 years old, I’m quite happy with that.

“I missed all the Monday night insanity on live television that would make my autograph fee a lot more than it is now.

“But the people’s lives that I’ve been able to go talk to, at the prisons across this country, are well worth it. And today, that’s what I’ve done with the rest of my life. And I continue to do that, to tell people that you don’t have to live on drugs and alcohol, you don’t have to cover the pain, you can get relief, and you can walk a different path. And people respond to that, and I am thankful.

“I am very thankful to be able to come up and tell you that story. I am very thankful for the Cauliflower Alley Club because, in 1961, Nick Bockwinkel lived across the alley in a duplex across from the my family. I’m very thankful that I saw Nick Kozak, who used to take me surfing when I was in high school. Reggie Parks, the guys that I used to referee their matches when I was college. Terry and Dory Funk, who recruited me to go to West Texas State, after SMU. And Marshall [Adkisson/Von Erich], your grandfather recruited me to go to SMU out of high school — you didn’t know that I bet.

“This is a great organization. The things that they do for people that have gone on hard times is worth it.

“I want to thank the board of the Cauliflower Alley Club for honouring me with this award. I want to say God bless you, as you go out these doors tonight. Thank you for attending this year. God bless each and every one of you.”

— transcribed by Greg Oliver

RELATED LINK