In his 90 years on Earth, Joe Garagiola hit .316 in a winning World Series, called some of baseball’s greatest moments, hosted national TV programs, emceed an election-eve special for President Gerald R. Ford, announced dog shows, and promoted Dodge cars.

But it would be hard for him to top the mirth of the day that Rip Hawk failed to bust up a vinyl record.

The funny stuff occurred during Garagiola’s successful run as play-by-play man on Wrestling at the Chase, the legendary show that beamed pro wrestling to the masses from the elegant Khorassan Ballroom at the Chase Park Plaza Hotel in St. Louis.

Garagiola was preparing to interview Gorgeous George, who, in the twilight of his career, had cut a record that he was eager to promote. Ever the mischief-maker, Hawk set out to disrupt the segment.

“I jumped out, grabbed this record and hit [George] over the head with it. But that thing wouldn’t break! It was one of those records that wouldn’t break. I didn’t know what it was. I hit him several times with it and he just looked at me like I was a dummy,” Hawk said in an interview before his death in 2012.

“Garagiola is calling me a madman. I said, ‘Ah, shut up, you spaghetti eater!’ People were upset because I tried to take advantage of Gorgeous George and Garagiola but it was funny as hell.”

Garagiola’s duties behind the mic at the Chase were footnotes to his Hall of Fame career as a broadcast personality and mentioned in passing, if at all, in obituaries following his death March 23.

But there is little doubt that his colorful, every-man style legitimized Wrestling at the Chase on KPLR-TV and set an early standard for TV wrestling.

“You talk about sports entertainment; really, Joe kind of gave you the first touches of it,” said author Larry Matysik, a long-time front-office worker in the St. Louis promotion who called on Garagiola from time to time for his wrestling recollections.

“He would call it like a fan would call it and put the humor in it. You put those two things together and he made it special,” Matysik said. “He was well-known because he was doing the St. Louis Cardinals broadcasts, so it helped to have a local guy doing it. Really, he just bridged the gap with sports entertainment and wrestling. He gave it a bigger footprint.”

It didn’t take long after the Chase show debuted on May 23, 1959 for Garagiola, 33 at the time, to conclude he was in on something special.

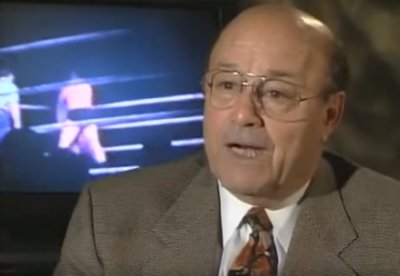

“The fact that you were in the Khorassan room put you immediately, immediately, a cut above any other place in the entire country,” he said in Matysik’s 1999 documentary Wrestling at the Chase: A Look Back.

Joe Garagiola reminisces in the 1999 documentary Wrestling at the Chase: A Look Back.

“I thought, what a concept. This is so different, wrestling and the Khorassan room. But I tell you, it turned out to be an event,” he said.

As an announcer, Garagiola never pretended to be a wrestling savant by conveying the names of complicated holds and takedowns. Instead, he relied on his natural wit and bonhomie to keep viewers interested and entertained.

“All I do is kid it along and try to act funny. Everyone seems to like it. The sponsors like it and the fans like it,” he said to the Pittsburgh Press in 1960.

But, Garagiola told the Press‘ Lester J. Biederman, not every wrestler was so enthralled with his clever commentary. Without naming names, Garagiola related the story of a grappler whom he called “yellow” on the air because he was taking such a fearful whipping.

“Well, the next show, the wrestler came to ringside looking for me. Said he had seen the tape of the program and didn’t like the remarks I made about him. He had fire in his eyes and you never saw a man more diplomatic than I was.”

Eventually, Garagiola talked his way out of a beating by explaining he was just conducting normal business. “No sense in us getting in each other’s way. I suggested he do his job and I’d do mine and we’d both stay in business and make out all right. Darned if I didn’t convince him.”

Matysik said Garagiola kept a respectful tone in interviews with fan favorites such as Lou Thesz and Pat O’Connor, but really shined when needling the likes of heels Hawk and Gene Kiniski.

“He was like a bench jockey in baseball, which is something people hadn’t seen before. He just brought it to a different level. He put a different feel on it,” Matysik said.

In fact, Hawk — real name Harvey Evers — was a top-rate prankster and a perfect fiendish foil for the tongue-in-cheek Garagiola.

“Joe Garagiola and I, people thought we were deadly enemies because one night I called him a spaghetti bender and word got out that I hated Joe. He used to make remarks at me and call me Barney Rubble. We went on back and forth. The people wanted it, so we gave it to them,” Hawk recalled.

Since the business shielded itself from public exposure in those days, Hawk and Garagiola often retreated to a back room at Stan Musial & Biggie’s restaurant, a steakhouse near Forest Park co-owned by the Cardinal baseball great.

“We had to go out to his restaurant in St. Louis to meet and do any drinking together. [Cardinals announcer] Jack Buck was always there. So we had pretty good times. But we had to hide out. We didn’t want to ruin that image the public had of us,” Hawk said.

On one occasion, Garagiola taunted Hawk during a TV show circa 1960, saying the tough guy’s head looked like a soccer ball that Garagiola’s friends played with when they were kids. Then the ex-baseball catcher got on Kiniski about the Canadian legend’s voice, saying it sounded like a bag of razor blades.

As Matysik recalled, Hawk and Kiniski proceeded to chase Garagiola around the outside of the ring until a referee was dispatched from backstage to calm down matters. St. Louis promoter Sam Muchnick was irate, tongue lashing the two heels for embarrassing his personal friend Garagiola and, by extension, Wrestling at the Chase, with their manic actions.

“Kiniski and Hawk just hung their heads and took it because nobody in those days wanted to get Sam mad,” Matysik said. Later that night, though, Muchnick went to a popular bowling alley to get a bite to eat and heard Kiniski and Hawk in the background, hamming it up.

As Matysik said: “Sam goes out and there’s Hawk, Kiniski, and Joe Garagiola. They’re all laughing and having a hell of a time. Sam says, ‘I thought you guys were mad at Garagiola.’ Garagiola says, ‘Oh, they didn’t tell you? We had all that worked out ahead of time. Did you like it?'”

Garagiola could be just as humorous behind the scenes as he was on camera, Hawk remembered.

One night, after matches at the Khorassan wrapped up, Hawk and Garagiola went out for a drink with a group that included wrestler Rock Hunter; Muchnick; his office assistants, Bill Longson and Bobby Bruns; beer impresario August Busch; and Harold Koplar, founding owner of KPLR.

Hunter stepped away and, after about an hour delay, appeared with his date for the evening.

“I’ve got to tell you it’s the ugliest girl I ever saw in my life,” Hawk laughed. “Joe Garagiola got up and said, ‘Oh, God, she looks like her face was made up with Bon Ami!’ That’s a cleaning fluid you used to clean toilets with. That broke everybody up.”

As it turned out, the woman had previously threatened to sue Muchnick, alleging she had been hit by a chair at a match some time before.

“So Sam pitched a real fit there that night but August Busch and Koplar, they thought it was the greatest thing that happened. Garagiola, he laughed like hell. He thought that was funny. He even brought it up on his TV show one time when he was doing a New York Yankee game,” Hawk said.

Garagiola was the voice of St. Louis wrestling until April 1962, when he left to join NBC. While he’d miss a few shows now and then because of other duties — brother Mickey pitched in and did some ring announcing — Garagiola also would fly from spring training in Florida to make his wrestling gig.

“It may be a peculiar way of making a living but I like it,” he said of the sport. Years later, Garagiola kept his ties with St. Louis wrestling, keeping the crowd in stitches during a private function at Muchnick’s retirement party in 1982.

“I’ll get people even today who say, ‘My grandfather used to watch it when Joe Garagiola was doing the announcing.’ That was 50 years ago,” Matysik said. “Joe had no bones about wrestling. He said it was one of the most enjoyable, entertaining times he had. He recognized what it meant in the community.”

Named to the St. Louis Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2008, Garagiola received the baseball hall’s Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasting in 1991 and the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014.

In the end, the accumulated fame, glory and funny stuff paled in comparison to the fact that Garagiola never outgrew his humble roots as the son of immigrants who lived in a rough section of St. Louis known as “Dago Hill.”

Hawk sat with Garagiola in the locker room not long after his buddy made a much-talked about appearance on the Jack Paar Tonight Show, then the reigning champion of late night TV.

“Joe came in, he was a big hit on that show; he really was. He said, ‘Hey, you guys see me on the Tonight Show?’ We said. ‘Yeah, Joe.’ He said, ‘Look what I got over there. They gave me a pair of shoes with my name in gold. That ain’t bad for a little ole’ Italian guy. is it?’ We said, ‘Not too bad,’ ” Hawk said.

“He was really happy at that time and he went on to be successful, as everyone knows. The thing about it is Joe never forgot where he was from. He was a real nice guy.”