When it comes right down to it, famed wrestler and announcer Lord James Blears, whose “Tallyho!” cry ended with his death this week, was more proud of his survival during World War II than anything he did after.

“Escaping from the Japanese in World War II,” he reminisced in 2002. “I wrestled my way off the submarine.”

James Ranicar Blears, who had turned professional wrestler at age 17, was a British radio officer on the Tjisalak, a Dutch merchant marine ship during the Second World War. Japanese torpedoes hit the ship and sunk it on March 26, 1944. The surviving sailors were pulled from the water. On board, the captors started killing their prisoners. An Olympic-calibre swimmer, Blears leapt overboard as gunfire surrounded him. He swam into the wreckage and waited — and waited — until a U.S. destroyer arrived three days later.

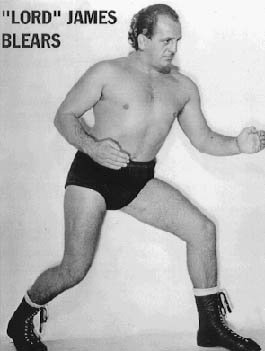

Lord James Blears. Courtesy Chris Swisher, www.csclassicwrphotos.com

The Americans gave him a can of peaches, and every year, on the anniversary of his rescue, he opened another can of peaches.

Once the war was over, his story was an easy way to garner attention. “In those days, the publicity guy in the wrestling office used my story all the time because I was captured by the Japanese,” he explained.

Among his colleagues, however, it was a different story. “People wanted to forget about the war and get on with living,” he said. “You don’t forget about all that you’ve seen. You never forget the experiences, but you just move on.”

And Blears sure did a lot of moving during his life. Details of his passing, as reported by the Wrestling Observer, are still forcoming.

Born August 13, 1923 near Tyldesley, England, near Manchester, Blears learned his future trade at the YMCA. He turned pro in 1940 at age 17, taking bookings where he could during the war; the travel as a radio officer actually allowed for matches in exotic locales such as Argentina, India, Australia, Canada, and in the United States — Tampa, New York and Nashville. He wrestled at home, and in France after the Germans had been driven out.

All that part-time grappling was a good set-up for his arrival in the United States to wrestle in 1946.

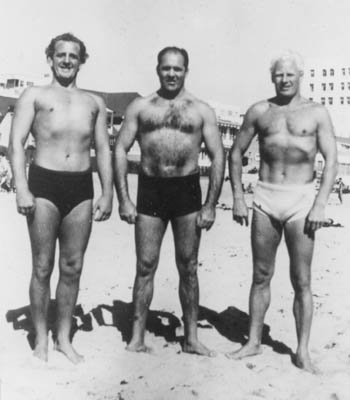

Arriving in May, Blears fell in with a couple of Canadians who had served their country in the Navy as well: Stu Hart and Sandor Kovacs. The trio shared a lodging in New York City.

“We had to get an apartment. In those days, you had to have a base. We found a place at 101st Street. It was a nice building and we got what they called a railroad apartment,” Blears said, explaining that it was a long apartment, with the toilet as you went in, then a room, then another room, the living room, then the balcony. “We shared the rent, $45 a month. Back then it was a lot of money.”

Blears, Hart and Kovacs would all end up marrying New Yorkers.

“My wife was engaged to an Italian lawyer. Italians liked to make sure that their beautiful daughters were getting married to someone with a good job,” he recalled with a chuckle. “I didn’t have a dime. I came every night with a black eye or a broken nose or something. I met the family. There’s one guy, one of her brothers, was okay with me. He liked me. But they’d introduce you to all the family. All the family arrives, and here I come with a broken nose, cauliflower ears.”

But, he added, “it worked out fine.”

Blears competed at 195 pounds. “I wrestled the heavyweights so I got a good lesson. I was wrestling all the heavyweights. I had a flying-through-the-air style, a lot of dropkicks, flying around. I was pretty good, so I could have matches with these big guys.” He especially credits Angelo Savoldi, Milo Steinborn, Joe Savoldi, Gino Garibaldi, Tony Marrelli and Antone Leone as men who helped mentor him.

In 1947, Blears went Hollywood, working for California promoter Hardy Kruskamp as Jan Blears (Jan being the Dutch version of James). “Jan’s favorite hold or method of attack is to dropkick an opponent silly and then give them what he terms the ferris wheel finisher,” detailed a program. “After he has an opponent groggy he jumps and straddles their neck, putting a leg under each arm and then forcing himself forward he swings through the air with the foe and at the end the opponent is in a pinning position and condition.”

Surrounded by the colour of California, Blears created a backstory of being a nobleman to stand out.

“What with his monocle, his regal strut and his vaunted fearlessness, James Rancier Blears has created quite a commotion in American wrestling circles,” promoted the NWA Official Wrestling magazine in February 1952.

Three years later, he was a big star.

The noble James Rancier Blears. Courtesy Chris Swisher

“We didn’t know whether to kiss, curtsy or cut ice. But His Lordship made it easy. He stuck out his paw for an American handshake,” wrote a “commoner” in a Sacramento Union piece in 1955. “‘I say now,'” His Lordship responded, “‘I’m very glad to meet you press fellows. Have a seat. I will be delighted to give you an interview.'”

He explained his pedigree. “Myself, I am Lord James Ranicar Blears. The title has been in my family for hundreds of years. It started in 1170. My father is Lord James Edwin Blears, and, as the oldest son, I inherit the title.”

Captain Leslie Holmes was Blears’ second from roughly 1945 to 1960, and his best friend. Like Blears, Holmes served during the war, as a captain in the British Army, working on tank recovery.

Nick Bockwinkel was a fan of the duo. “What was so great about Captain Holmes was that no matter how the announcer, Jules Strongbow or whoever it was, took and tried to demean his Lordship in some capacity verbally, Captain Holmes with typical British eloquence and savoir faire, would put the announcer — Jules Strongbow or whoever it was — put him down, put down what he said, and almost just dispense with him because he was just a commoner, a peon.”

Another elite pairing was with Lord Athol Layton, whose peerage came by way of his Australian roots.

“There is one other genuine British nobleman in the American ring. He is my good friend, Lord Layton,” Blears ballyhooed in the 1955 interview. “He is an authentic lord. All the rest are impostors. They saw my success and they copied me.”

In 2002, Blears told the story more the way it actually happened. “I went up to wrestle in Toronto, then I told Layton … I said, ‘C’mon down. Let’s hit that New York area, not New York City, but from Buffalo all the way to the East Coast. We got together and it clicked. We were together, I think, for nine months, seven days a week.”

Blears’ earlier tag team with Gene Kiniski was something very far from nobility.

“He was great, knocking people down, knocking the posts down, the big giant. So I said, ‘That’s the man for me, and we teamed up,” Blears remembered. “We were tag team champions for three years.”

“We looked different. He was a big, rugged bastard. A big, rugged tough guy,” said Blears. “He’d go plowing into 50 people. We were attacked every night. In California, Gene and I, I’m not kidding you, had to fight our way out of the ring. We couldn’t get out of the ring. The fans wanted to kill us. In those days, you could go out swinging. Now, you hit one guy, you’ll get sued. Back then, you just battled your way out of the ring. Gene, he’d say, ‘Let’s go! Okay Lordski, let’s go!’ He always called me Lordski…. Boy, he’d go swinging those arms, and I’d be behind him, protecting his back.”

Kiniski would keep in touch with Blears through the years, and shared a glimpse of their conversations. “He starts laughing like a son of a bitch as we start talking about old times, and the shit we used to do, and all the blondes after the matches. He just died laughing,” Kiniski said.

A frequent opponent for Blears and Kiniski were the massive Sharpe brothers, from Hamilton, Ontario. Blears had actually met Ben and Mike during the war, while on leave from the Merchant Navy. “We wrestled them a hundred times. If you put Gene and I against the Sharpes, it was a sellout, without even knowing what was underneath the card. I’m not boasting, it’s true.”

For all the wrestling that Blears did through the years, it was his decision to accept a booking in Hawaii in 1955 that changed his life. He fell in love with the island. Initially, he found a place for his family in the Steiner Building which sat on the grounds of the current Waikiki police station. He helped promoter Al Karasick (Hawaii Wrestling Mid Pacific Promotions) secure talent.

The Blears name would be associated with 50th State Wrestling from early 1961 until the promotion’s dying days in 1979. He was a full-time wrestler from 1961-65, but then took himself off the active roster, focusing on hosting the TV show, doing locker room interviews and the play-by-play announcing.

“Lord Blears, what a guy. He was just perfect for there as a commentator. He would salute everybody,” Rick Martel said. “He had it, he really had the flavour, the way of doing things in Hawaii.”

What the fans didn’t know was that Blears was promoter Ed Francis’ matchmaker as well.

He had a huge influence on the wrestling scene in Hawaii, and commanded respect — and love — from colleagues.

“When I used to tell people in my business that I had to check with the Lord before I do anything, they thought I was religious — until they found out it was Blears,” King Curtis Iaukea said in a 2005 Honolulu Advertiser interview. “He was the envy of the whole wrestling business.”

Hawaii seeped into his family’s blood as well. His son, Jimmy, would grow up to be a surfing champion (he died in 2011), and his daughter, Laura, was the first woman to surf in a men’s professional tournament and later posed for Playboy. Tallyho himself is a former senior men’s surfing champion in Hawaii, and served as a commentator on surfing broadcasts.

It was Sam Steamboat that taught Blears to surf, a part of a barter deal. “I started him wrestling. He was on Waikiki beach, he was a beach boy, but he had a terrific body on him, worked out surfing every day,” Blears recalled. “I said, ‘I’ll teach you to wrestle if you teach me how to surf.’ So he said, ‘okay.’ We went out every day on the board and he taught me how to surf, and we went down to the gym, and I taught him how to wrestle.”

Blears was also instrumental in a number of other wrestlers getting started, including Iaukea and Don Muraco. It was Blears’ idea to put a mask on Dick Beyer, who had been teaching at Kaimuki High School, and he became a sensation as The Destroyer.

The other place that Blears had a major impact on was Japan, perhaps surprising given the horrendous incidents he saw as a prisoner of war.

“I went to Japan a lot,” Blears explained. “I was the first guy to get Japan started. Rikidozan called me up. He came to wrestle in the U.S.A. He came to Hawaii.

“He came over and said ‘Get four American wrestlers, and come on this date for one month.’ I got four guys — three guys and myself. We went over and that was the first time they had American wrestlers.”

After Rikidozan was killed, Giant Baba asked Blears to help him get talent for All-Japan Pro Wrestling. Publicly, Blears was billed as the President of the Pacific Wrestling Federation. He was instrumental in talent ranging from Don Leo Jonathan to the British Bulldogs (The Dynamite Kid and Davey Boy Smith) going to Japan.

Blears continued to visit until the early 2000s. “I go over there about twice or three times a year, hobble on the plane. They always take care of me,” he said. “They never forget the little leaders, the ones that began things. They always respect that. They never forget that, never.”

Fans of 50th State Wrestling will never forget Tallyho Blears either. He was, simply, an institution.

When Karasick wanted to sell the promotion, he first approached Blears, who turned him down. Ed Francis, a former world junior heavyweight champion, borrowed $10,000 to buy the company, and Francis called Blears in Los Angeles, asking him to serve as the booker.

The two became a tag team, securing TV for the promotion, first on Channel 4 ABC, which ran a live studio show on Saturdays. When ABC balks at signing a contract with the wrestling company, 50th State Wrestling moved to Channel 2 NBC. The hour-and-a-half live show every Saturday was unique because it had to be.

Generally, the Hawaiian promotion just employed 10 wrestlers, so there was a lot of time to fill, but not overexpose the stars. Usually, that meant two matches, for about 30 minutes, a demonstration of holds for another 15 minutes, some time answering fan mail, and then the rest of the time was filled with some of the most creative interviews every done.

“These guys, in an hour-and-a-half show, they only had one match, or two matches on TV, and the rest were interviews. That’s when I realized that people cared more about what the guys were saying,” said Bill Watts. “They already knew that in Hawaii, because they had such a limited amount of talent staying, they would only have the big names when they were coming back and forth from Japan. So they developed a new way of promoting their business with all these interviews.”

The company ran house shows on the various islands, but usually there were only a few shows a week. The main arena was the Civic Auditorium in Honolulu, which held about 3,000 fans. The H.I.C. Arena was built and 8,000 fans could come in, and the promotion ran that location monthly.

In an interview with Mike Rodgers’ Ring Around the Northwest newsletter, Blears explained his goal building stars.

“[T]he people in Hawaii had to get to know the wrestlers. It is hard to explain,” Blears said. “Many of the biggest names on the mainland were not known in Hawaii. We catch one or two guys going to or coming from Japan but the program we had been working on for four weeks would draw the house.”

James Blears, on the left.

Francis and Blears survived a brief invasion by Roy Shire’s San Francisco promotion, eventually forming a small partnership. Come 1973, the American Wrestling Association became the de facto promotion in Hawaii, and Blears dubbed his soundtrack each week. But the live shows dropped off to monthly instead of weekly. At some point, Francis sold the rights to the territory to Steve Rickard of New Zealand, and promoters such as Lia Maivia ran the islands, and Blears helped here and there.

When wrestling expanded through cable television in the 1980s, Blears was one of the feature announcers on AWA broadcasts, generally taped for ESPN in Las Vegas.

Reached in January 2002, Blears was his typical ebullient self. “I’m 78 now. Jesus, I can’t believe it! Time flies. How long do you live!”

At the time, he said his health is still pretty good “except for my hip. I’m supposed to have an operation on my hip, but I keep putting it off.” The hip kept him from swimming.

His old friend Dick Beyer said he was just stubborn. “He’s in a nursing home, and the only reason he’s in a nursing home is because he doesn’t want to go and have his hips replaced. I tried to give him a pep talk about getting his hip replaced. He’s been suffering for 10 or 15 years.”

According to reports, Blears died at age 92. Funeral arrangements are not known.

RELATED LINK

How Lord James Blears survived a torpedo and wrestled his way off a Japanese submarine