Eiji Ezaki, better known to the wrestling world as Hayabusa, has died. He was 47 years old. His high flying influenced the next generation of professional wrestlers.

“I remember spending $50 for FMW tapes from HMV just to see your matches,” posted New Japan and Ring of Honor star Michael Elgin upon hearing the news.

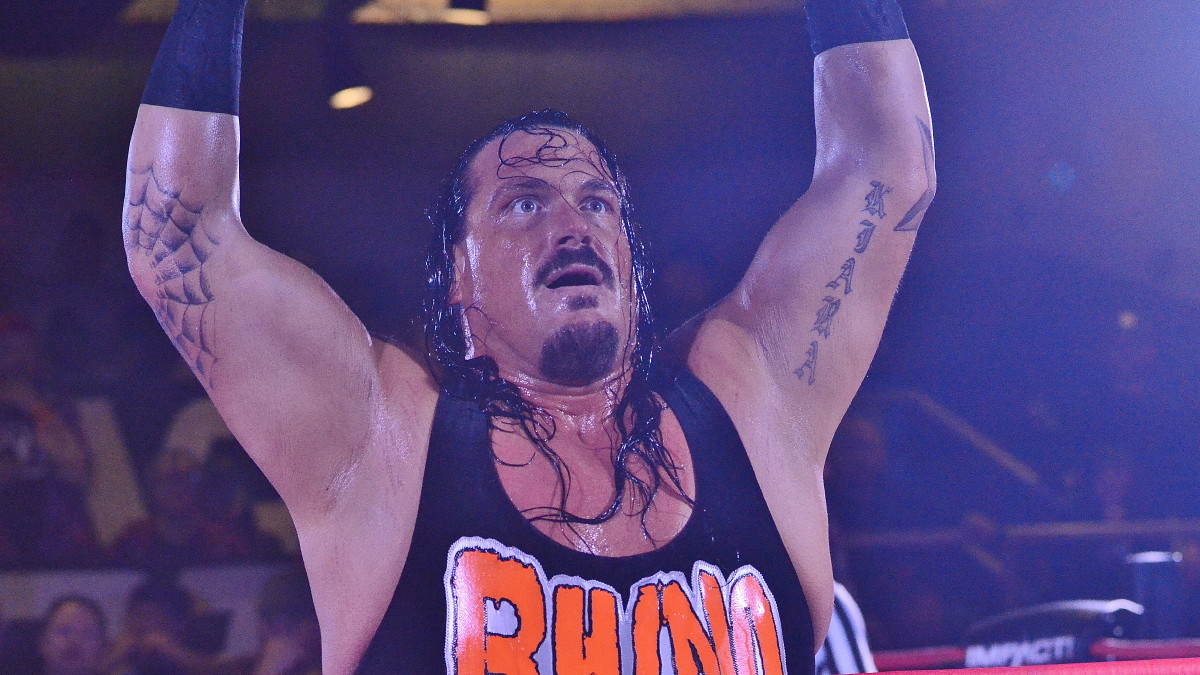

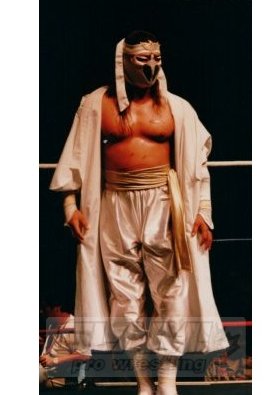

Hayabusa in 1997 at a Terry Funk retirement show in Amarillo, Texas. Photo by George Tahinos

Anthony Nese, who worked in TNA and is a featured performer in EVOLVE, tweeted out something similar: “He was the reason I started watching international wrestling. I would do Phoenix Splashes in the backyard all the time.”

Equally influential was the reminder of what can go wrong for professional wrestlers.

“Sad to read about Hayabusa. An amazing performer, who literally gave his body for the industry we love,” tweeted Ring of Honor’s Steve Corino. “A true innovator and inspiration.”

Corino was referring to an October 2001 incident in Japan where Ezaki’s attempt at a quebrada (Chris Jericho’s lionsault) went awry and he landed on his neck. Ezaki was confined to a wheelchair from that point on.

Jericho was asked about the incident by journalist Alex Marvez a few months later, and whether he’d seen the accident.

“I don’t ever want to see it. I know Hayabusa. We worked in Mexico in 1994. The guy was one of the best I’ve ever seen. I don’t want to see the footage. I don’t want to see the footage of Sid (Vicious) breaking his ankle. That stuff happens. It could happen to anybody at any time,” Jericho told Marvez. “I have reconsidered doing the move a couple of times, like when a rope has broken or I’ve slipped off the ropes. I just hope I always make sure to be more cautious and completely be sure-footed. But I got away from doing the move in every match for other reasons. I don’t use it as much unless I use it to get a pop by having someone move out of the way or something along those lines. It has nothing to do with Hayabusa. I got away from it beforehand because if I’m still in the business in six or seven years, I don’t want to have to rely on a gymnastic flip. (Keijo) Muto did flips as his trademark and look at him. You just never know. It’s like in football or hockey or any contact sport. Every time you’re in the ring, you put your life in danger. It’s a very serious contact sport.”

Post-wrestling, Ezaki tried a career as a singer. Just last year, there was a moving moment at a wrestling show in Japan where Hayabusa was wheeled to ringside, but, with the help of a cane, got into the ring to acknowledge the crowd.

Toronto’s Daniel Iurincic is currently in Japan, learning his trade, and met Hayabusa a week ago. “I thought it was the coolest thing he saw me wrestle. We were a table apart at the merch table that night and to see the smile on his face as people came up to him for a picture and an autograph you could tell how much it meant to him in his heart,” Iurincic posted on his Facebook account. “After walking back to the dressing room from the merch table he rode off in front of me in his electric chair and I saw the struggle he had to get out of his chair to go into the washroom. Sad to think that’s the last image of seeing you.”

Born November 29, 1968, Ezaki began his career in 1991, coming out of the Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling (FMW) dojo, the promotion run by Atsuhshi Onita, who became the king of the “garbage matches.” Four years later, in 1995, Onita worked against Hayabusa in from of 50,500 fans at Kawasaki Stadium in Kawasaki, Japan, in a Brass Knux Title Exploding Ring Barbed Wire Cage Match for FMW’s sixth anniversary. A year later, there was Terry Funk and Mr. Pogo beating Masato Tanaka and Hayabusa in a No Rope Explosive Barbed Wire Time Bomb Land Mine Double Hell Death Match.

Before those headlining days, Ezaki cut his teeth in Mexico and the lucha libre style, where he took the Hayabusa name. He also wrestled under the name H in Japan.

Matches with Jushin “Thunder” Liger in 1994 helped establish Hayabusa stardom.

Some of Ontario’s Joe E. Legend early matches in Japan were against Ezaki.

“I wrestled him many times in FMW when I 1st broke in to the business and before he was given the Hayabusa gimmick,” wrote Legend (Joe Hitchen) on Facebook. “He had ‘future star’ written all over him and I was thrilled (though not surprised) when he broke through and became a big deal in the industry. … I was green as grass when we worked and even though he was as well, I learned a great deal from him and I am grateful for the time and efforts he put in to our matches, even though he was just there to ‘put me over.’ So, a heartfelt THANK YOU to you my friend. I hope you got all out of life that you could in your brief time here. Your skills helped me greatly and I’ll always be indebted to you for that.”

Hayabusa poses with fans from North America, including SLAM! Wrestling’s Bob Kapur, in January 2008.

Hayabusa wrestled in the United States on a few notable occasions. He was on the “WrestleFest” show that was one of Terry Funk’s many retirements on September 11, 1997, in Amarillo, Texas, at the Tri-State Fairgrounds Coliseum. That day, Hayabusa teamed with Masato Tanaka and Jensei Shinzaki (later known as Hakushi in WWE) to defeat Jake Roberts and The Head Hunters, with Victor Quinones as their manager. There were appearances with XPW and ECW (appearing at Heatwave in 1998, teaming with Shinzaki against Rob Van Dam and Sabu).

Florida promoter Ron Niemi recalled using Ezaki on a few of his shows.

“I was lucky enough to have Hayabusa on several of my shows during his run in Florida in the ’90s and we all knew he was going to be a major star,” wrote Niemi. “I remember watching him vs Navy SEAL (LeRoy Anthony Howard) and knowing I had something very special happening in the ring that night that nobody had ever saw the likes of in Florida. Hayabusa even came to a huge party that Teri McKenzie Niemi and I were throwing when we lived in South Tampa and he was very cool and the stories from that night still live on to this day. Hayabusa was a pioneer and a true legend in the wrestling industry and he will be missed.”

According to Tokyo Sports, Ezaki died from a subarachnoid hemorrhage, which is bleeding in the brain.