There were two distinct sides to the wrestling life of Steve Rickard. He was a globetrotting grappler before becoming the most influential and important promoter in the history of pro wrestling in New Zealand. His knowledge of being on the mat earned him respect.

After all, Harley Race and Ric Flair defied the NWA Board of the Directors and exchanged the NWA World title for Rickard in 1984.

It’s a well-told story, but worth repeating, since it wouldn’t have happened without Rickard, who died Sunday in his native New Zealand, at the age of 85.

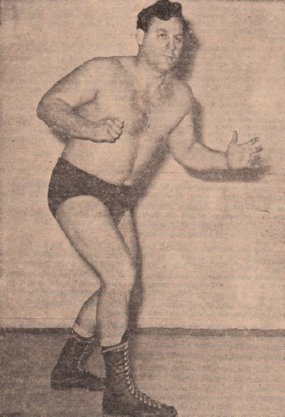

Steve Rickard

Flair and Race switched NWA World title without the approval of the NWA Board of Directors while on a

March 1984 tour of New Zealand. It was Race’s idea, in part to help the sagging business of Kiwi promoter Steve Rickard. As Flair said: “If Harley Race okayed it, it was hard for anyone to tell them different.”

In 2008, Flair talked about the title change with Simon Sweetman of the old www.nzpwi.com site: “Yeah, well, that’s one of those disputed times I’m talking about, that’s probably the 17th championship right there … but it’s not one of the ones that officially counts. We did that as a favour to your promoter down there; a man named Steve Rickard. This was before much in the way of TV down your way … and so we did that, as was the way then, agreed to drop the title, to help build the event, to help promote it. And it worked. It definitely worked. I had a good time down there.”

Tours of New Zealand were memorable for many wrestlers from North America, and Rickard was known as a honorable man.

“Steve Rickard was one of the nicest, fairest promoters I ever had the pleasure to work for. I was lucky enough to work for him three separate times,” Moondog Ed Moretti wrote in 2009.

Rickard was actually born Sydney Mervin Batt on September 3, 1929, in Napier, New Zealand. Amateur wrestling entered his life at the age of 14, and not long after he started working to support his mother and three younger brothers. He originally was a police detective, but bought the Hutt Park Hotel, and ran that for 15 years.

As an amateur in the 1940s, Rickard was a notable name in the conversation for the national championships. He trained amateurs and later pros.

An atlas is a good companion to figure out all the places that Rickard wrestled, as documented in a magazine article from the 1970s by New Zealand historian Dave Cameron: “Steve Rickard is rapidly becoming known as the greatest globetrotter in wrestling. In recent years he has made numerous trips to Australia, several to Singapore, and has wrestled in Canada, U.S.A., Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, India and right through the Pacific Islands New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Western Samoa, American Samoa, Fiji, Tahiti and Hawaii.”

That travel never stopped. Rickard continued to be involved in pro wrestling through the years. He was still on the NWA Board of Directors in 1994 when Shane Douglas famously threw down the NWA World title, and was president of the NWA from 1995-96. The Cauliflower Alley Club honoured him for his work in wrestling with an award at its annual banquet in March 1997 at the Sportsman’s Lodge in Studio City, Calif.

A notable run came as the “son” of the legendary King Kong Czaja in India, working as Young Kong. “The Indians liked him. The name alone was sufficient to draw them to his bouts by the thousands,” wrote Cameron. “At one stadium in India he found he was the only European wrestler on the bill, and it seemed only natural that the Indians would want their local favourites to win. Steve was booked against the home star, Tiger Sucha Singh, in a place called Zijayawada. It was a hard scientific contest with Steve taking the deciding fall after about 50 minutes. Spectators were storming the ring from all sides. But there was no need to worry. Steve was hoisted on their shoulders and carried from the ring. This is something a wrestler doesn’t expect when in another country.”

Historically, though, Rickard’s greatest contribution was probably as a promoter, and his rise parallels the story of television in New Zealand.

“We really didn’t get TV until ’64 and ’67 over the whole country. It used to start at three in the afternoon and finish at 10,” Bushwhacker Luke Williams recalled for the Ring Around the Northwest newsletter in June 2012.

The first professional wrestling show on New Zealand TV was the Australian promotion, Big Time Wrestling, put on by Jim Barnett. Lasted less than a year, but with Rickard involved with Barnett promoting some shows in his home country, it set the stage for his own show.

Rickard taped his first “On The Mat” show in 1973, but he’d promoted for years before that, under the Dominion Wrestling Union banner he had inherited from longtime promoter Walter Miller, and then as All Star Pro Wrestling. With only one main station in the country, TV1, there wasn’t a spot for his show; enter the TV2 station needing new programming.

The NZOnScreen.com website addressed the progression from there: “The first 14 episodes were taped in Auckland and briefly in Hamilton after which it found a home at the Canterbury Court Stadium in Christchurch; although the final season in 1983 was shot at the Auckland YMCA. On the Mat ran for a TV half-hour and had two commentators. Rickard described the technical aspects of what was happening in the ring and Ernie Leonard added colour. In 1981 Leonard moved to produce the show and Barry Holland came on as the second commentator and presenter. The commentators would announce the card to camera and then introduce and commentate on each match. Shows generally included two or three wrestling matches, an interview and/or an excerpt from an overseas match (usually from the US).”

The promotion was off and running and resulted in a boom in popularity for pro wrestling again — it had been really big in New Zealand before in the 1930s.

On The Mat ran from 1975 to 1983, and made stars out of the likes of Mark Lewin, King Curtis Iaukea, Rick Martel and Don Muraco. It also helped set the stage for homegrown Kiwi stars such as the Bushwhackers/Kiwis/Sheepherders, and Sivi Afi. Later, he promoted the show “The Main Event.”

In his autobiography, Life On The Mat, Steve Rickard talked of two talented performers he helped along the way: “Among the current crop of wrestlers are two who have made it to the top without any amateur back-ground, Peter Maivia and Siva Afi Peter Maivia is rated in the top 10 in the world while Siva is the current New Zealand and Hawaiian Heavyweight champion.”

As for the Bushwhackers, who were just recognized by the WWE Hall of Fame, it was Rickard who was key to their career. He had known them in New Zealand, and brought them into Hawaii, where he was promoting. Business wasn’t great there, but Butch Miller and Luke Williams met Roddy Piper and “Playboy” Buddy Rose, who invited them to come wrestle in Portland, Ore. “[We] did have a USA Visa which Steve Rickard had got for us for 6 months. Thank you Steve, that was a big thing you did for us,” wrote Miller in a 2002 online column.

Rickard saw all kinds of untapped markets on the smaller islands and other countries.

British wrestler Earl Black recalled one such attempt by Rickard: “In Singapore, promoter Steve Rickard had managed to get away from the old system of having rounds, like boxing, and brought in time-limit wrestling matches. On one show, a one-hour six-man tag team was advertised. The capacity crowd enjoyed the match, until the fall was taken after forty minutes, and the match ended. They considered that they had been ripped off, and that a one-hour time limit match, should actually last an hour.”

The Destroyer (Dick Beyer) told a story of “High Chief” Peter Maivia’s return home to Western Samoa for the first time in 15 years, for a bout promoted by Rickard. At stake was The Destroyer’s U.S. title, and like Flair and Race and the NWA World belt, it is an unrecognized title change.

“We could have wrestled three times in one day and still packed the house,” Beyer recalled with awe. It was one of the easiest nights he ever had. Though the fans were packed so tight their arms reached into the ring, they were putty in the hands of the skilled mat veterans.

“You talk about wrestling somebody and not having to do anything, and have the people want to come in the ring and kill you, that was the kind of match it was,” said Beyer. “All I had to do was grab an arm hold on him, boom! Maybe I grab a little hair, pull him down, and those people are halfway coming in the ring.” Naturally, Maivia went over, winning the U.S. title and setting off pandemonium. “I worked to where I got disqualified and he won my belt. We went out to dinner later — the promoter threw a dinner for his family, my family. I said, ‘I need that belt, because I’m leaving for New Zealand tomorrow, and I’m taking that belt with me.’ I got the belt back, and nobody in America ever knew that, or that the match ever took place.”

When Ed Francis decided to end his promotional days in Hawaii, and become a cattle farmer in Oregon, he sold the promotion to Steve Rickard. The Kiwi then brought in two partners, Rick Martel and Peter Maivia.

It was a short-lived partnership, said Martel. “We had some creative differences … I had the book there. It was really good. I brought in Roddy [Piper]. Hawaii was a small place. … You had to give them a really good show with hard working guys and you could draw some money. But Peter had just come in from New York, and he was trying to bring in Baron Scicluna, his friends. Nice guys, but hard-working guys they are not. No bumps. In New York, you could get away with that, the millions of people. Different style. In Hawaii, you needed hard-working guys that could take bumps. So Steve and I were kind of locking horns on that and different things. Finally, I just said, ‘Look, I can’t work this way anymore’ and just left. I remember the day I brought Roddy in. I was all excited. ‘Oh man, I’ve got Roddy Piper. The man is great.’ I remember we used to fly him in from New Zealand every month. The first show that Roddy was there, it was great, he was giving an interview, it was fantastic, the match, the whole thing. ‘Oh Peter, wasn’t that great?’ (imitating voice) ‘Oh, he’s okay, he’s okay.’ That’s when I knew.”

Rickard didn’t promote in Hawaii for all that long, returning to promoting around New Zealand. He had three sons, two of whom entered the wrestling business, and Martel knew them both well.

Tony Rickard was a referee. “Tony was the loud one. Tony loved the business, but he wasn’t big enough,” said Martel. The other son, Ricky, was a wrestler who had good amateur background; “He was a shy personality, he didn’t really like the wrestling business.”

Much of the history of pro wrestling in New Zealand was captured in the as-yet unfinished documentary, Wrestling Spectacular! A Kiwi Century on the Mat, at kiwiwrestling.com.

During the last years of his life, Steve Rickard suffered from dementia, and lived with his sons, Tony and Stephen, in Queensland, Australia. His wife, Lorraine, died in 2010.

His funeral will be late this week or early next week in New Zealand.