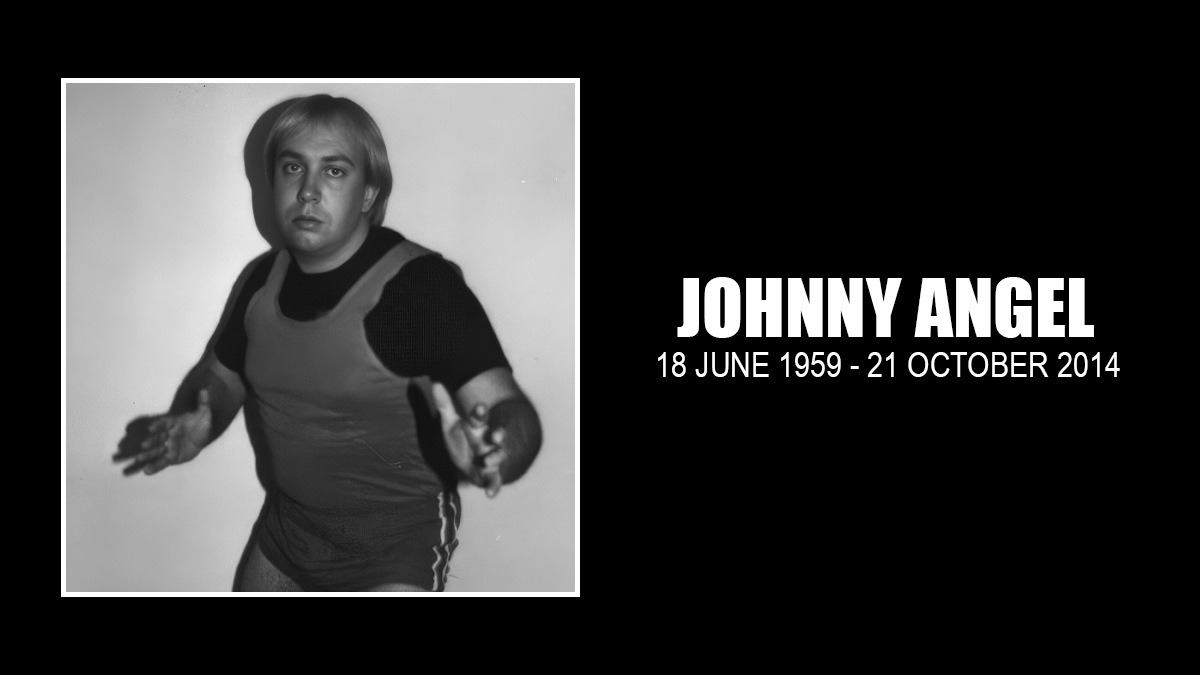

There’s a much better chance that you saw Johnny Lee Clary, the Ku Klux Klan member turned evangelist, on one of the many wildly entertaining talk shows, like Jerry Springer, or on religious programming, than you did during his brief career as 1980s professional wrestler Johnny Angel.

With his death on October 21, his long-time friend Don “D.C.” Drake said that the versions of Clary were all one in the same.

“The character you saw there was his wrestling character,” said Drake. Instead of riling up the fans, inciting hatred, “he stirred them up the other way” when he was a preacher.

Clary died at his home in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, of a heart attack.

He was a well-known figure from his numerous radio, TV magazine and newspapers appearances, including Fox and Friends, Fox News, Oprah, The 700 Club, Queen Latifah, Phil Donahue, Charisma Magazine, Guidepost, and Christianity Today.

But before that, he was a professional wrestler.

According to his website, Clary said that he and his brother, Terry, were trained by Danny Hodge in Oklahoma in 1983. Contacted on Thursday, Hodge didn’t specifically remember the Clarys, but said that he trained “quite a few” people over the years. “If I seen somebody that needed some help, I would try,” said Hodge.

“Terry began his career as the ‘Sugar Boy,’ while Johnny broke in as his manager, Der Kommissar, named after the hit ’80s new wave song, by ‘After The Fire,'” reads the website. Later, Johnny Clary bleached his hair blond and became Johnny Angel.

While Clary did work a few smaller areas, such as Arkansas and Kansas City, in the waning days of the territorial system, it was in the National Wrestling Federation that he had his biggest run — and that was primarily as a manager.

Drake said Clary was originally hired to do publicity for a show in Kalispell, Montana, on local TV and radio stations, as Clary owned a ring, and trucked it in from his home in Oklahoma.

“He really stirred that place up,” said Drake. “It was over 5,000 people, I believe.”

Portraying a madman, Drake had Johnny Angel as his manager for part of his run in the NWF — a far cry from the man Drake actually is, quiet and thoughtful, and behind-the-scenes he was the producer of the NWF TV show.

“He was a great character. He got major heat with the crowd,” said Drake. “He was just an antagonizer. There was something about Johnny that made people hate him. I can’t explain it. Johnny had a way about himself that he was able to antagonize people.”

In-ring, Clary wasn’t as talented. “His wrestling skills weren’t that great, but his ability as a manager and as a publicist was excellent.”

During an interview in December 2012, Clary shared a story from that big show in Kalispell.

“We had all the babys and the heels in the dressing room. There was nowhere else to be. It was at the fairgrounds that day … We were all joking and cutting up. I remember Sgt. Slaughter came in there and Sergeant was mad because I was working a gig against Slaughter, I was the heel and of course Slaughter was the baby. Slaughter goes, ‘This time I’m leaving.’ I said, ‘C’mon Bob? You don’t want to stay?’ He said, ‘No, no, if you guys don’t start kayfabing we ain’t gonna have no business left.’ I remember I said to Don, ‘Don, he’s ticked off.’ Don said, ‘Oh, well, he’s a star, he’s got that star syndrome. We’ve got to lighten up and have fun here. That’s what it’s all about.'”

With the NWF’s implosion, despite its presence on SportsChannel — in-fighting amongst the partners scuttled a potentially big deal that would have propelled the promotion into the 1980s wrestling mainstream — Clary stopped wrestling by 1988.

He had a new calling. The Ku Klux Klan saw the fiery Clary as a great spokesman for its racist beliefs. A KKK member since the age of 14, Clary rose through the organization, from being a bodyguard to David Duke to Imperial Wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Like Drake, Bobby Fulton of the Fantastics first met Clary via a ring rental in Oklahoma. In this case, the show was in Ponca City. “When I got there, there was this guy, and he was wearing a calvary unit’s rebel hat” from the Civil War, said Fulton. “I don’t even know why I asked him. I said, ‘Why are you wearing that?’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’ It was Johnny Lee Clary. Three days later, I’m watching Oprah Winfrey — and guess who’s on Oprah Winfrey! Johnny Lee Clary, and he was the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and I didn’t know it!”

“I never knew he was part of the KKK. I had no idea until after the fact. One day I was home and I saw him on, I think it was Morton Downey Jr. Show. I was shocked,” said Drake. “The character you saw there was his wrestling character. Now, what was interesting about it is my wife was African-American and he never acted any differently.”

In 2012, Clary could only chuckle his past. “[Drake] used to get the biggest kick, because with my background, he said, ‘I never knew, because you never told me that you were a racist at that time,'” said Clary. “I didn’t talk that stuff when I was in the business.”

On his website, Clary addressed his defection from the KKK to becoming a Christian evangelist: “Johnny began to struggle with the beliefs of the Klan, such as their praise of the Holocaust where 6 million Jewish people were slaughtered, and the fact that Nazis and Skinheads were now associating with the KKK committing crimes which included all sorts of Civil Rights violations including murder, which Johnny disagreed with. Riddled with torment, angered over a false arrest in Tennessee on a weapons charge, disgusted with internal bickering between the various white supremacist organizations, being totally harassed by the F.B.I. as well as the United States Secret Service, seeing people close to him being hauled off to prison, and the discovery that his girlfriend was an informant for the FBI, Johnny Lee left the Klan.”

Clary turned to the Bible and began preaching.

About two decades after first meeting Clary, Fulton remembers being in the car listening to talk radio in North Carolina, and he heard his name. “It’s Johnny Lee Clary, and now he’s a preacher and he talked about how he changed his life, asked God to forgive him about the Ku Klux Klan, and how a lot of people were after him and wanted to kill him because he walked away from that lifestyle to go to the Christian lifestyle. I couldn’t believe it.”

Clary’s fascinating story was an easy sell to Christian programming and the speaking circuit.

On a much smaller scale, Drake brought in his old friend to New Jersey in 2004, to address the addiction clinic where he worked.

“He had me speak about all the addictions that I had, racism and hatred and drinking and all that kind of stuff, and tell my story,” recalled Clary.

To Fulton, Clary’s epic journey recalled the book turned movie, Little Big Man, where the protagonist, Jack Crabb, who is 121 years old, recounts his colorful life story to a historian.

“I always thought it was like that movie, Little Big Man, because Dustin Hoffman, he’d run into a guy and he’s one way, and all of a sudden it’s 20 years later, and he was another way. That’s the way I thought of Johnny Lee Clary.”

The viewing for Johnny Lee Clary is Monday, October 27, 5-8 p.m., and Tuesday, October 28, 9-11 a.m., with a celebration of his life at 11 a.m., all at the Family Worship Center, 8919 World Ministry Ave., Baton Rouge, Louisiana.