The passing of Ciclon Negro on February 20, 2013, didn’t get the press a name of his stature deserved. He was a headliner across the globe for many years, during a career than ran from 1956-84. But little was written — or known — about him. It turns out that he and his wife, Cheryl, had made a conscious decision to distance themselves from the wrestling business.

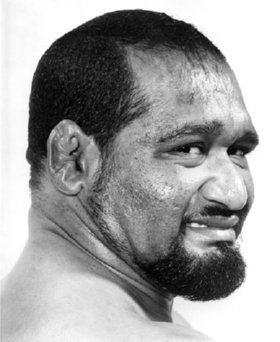

Cyclon Negro had one of the greatest faces ever in the history of professional wrestling.

“Once he was retired from actively being in the business, he just disappeared out of sight. We didn’t stay connected with anybody in the business,” said Cheryl, the second wife of Ramon Eduardo Rodriguez. “He was just done with it. We wanted to live what we considered a normal life. That’s what we did.”

After his death in Melbourne, Florida, there wasn’t even a funeral for colleagues, from wrestling and from his 15 years as a welder, to come pay their tributes.

But the story of Ramon Eduardo Rodriguez deserves to be told.

He was born April 7, 1932, in San Felipe, Venezuela. An athlete youth who grew into a 6-foot-1, 250-pound physical masterpiece, Rodriguez was trained as a welder. His first love, however, was boxing.

A fanatical gym rat — he would work out religiously until hip surgery ended that obsession in 2003 — Rodriguez entered professional wrestling in 1956. Too heavy to be a boxer any longer, he had seen the pro wrestlers and figured he could do that. Initially, Rodriguez was Ciclon Venezuelano, the Venezuelan Cyclone.

Six years younger than Rodriguez, Omar Atlas (Omar Mijares) met the boxer-turned-wrestler in a Caracas gym. They became fast friends, and their careers intertwined for years; they would even team as brothers in Florida, and to this day, many think they are actually brothers. While they were not related, Atlas’ first wife was Rodriguez’s first cousin.

“He introduced me to professional wrestling,” said Atlas, who acted as a second to the star, a pseudo-cornerman, bringing the water and carrying the robe. “He had a big name in Venezuela, a big, big name”

In 1958 Rodriguez went to Europe and spent six years, off and on, wrestling in Spain, France, Belgium, England, Germany and Italy. Naturally, he later invited Atlas to Europe as well, to become a pro wrestler as well. “He said, ‘Come in to Spain.’ I don’t have the money to go over there. I asked my mother-in-law and father-in-law, and everybody put their money together, and I left for Spain.” When Atlas hurt his shoulder and could not wrestle, Rodriguez’s big heart meant that he took care of his friend financially.

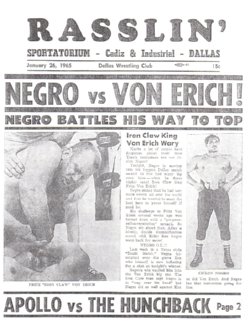

Blackie Guzman of Houston was a scout of South American talent and Rodriguez was brought into Texas and renamed Ciclon Negro (or any number of variations thereof, most commonly Cyclone Negro).

Ciclon Negro as a young boxer.

In 1961, Lalo Rodriguez made his debut in New York for the Capitol Sports promotion, the forerunner of the WWWF. “Lalo” was an old nickname, and what Atlas actually called his buddy. Though the stay in the big territory was brief, he did get to work in Madison Square Garden and met many men who he would wrestle in the future.

Maybe it didn’t click in New York because Lalo Rodriguez was a babyface, and Ciclon Negro was excellent as a villain.

“He loved the business and he loved the power to get the people to scream,” said Atlas. “It was in his blood.”

His widow concurred. “He liked being a babyface, but it was more fun being a heel. He was good at it,” said Cheryl Rodriguez. “The business to him was like a big game, and he was like a big kid.”

Probably his most famous bouts came against Dory Funk Sr., and all the Funks for that matter, in Amarillo.

“Cyclone Negro was another very talented individual and one of the nicest guys you’d ever want to meet,” wrote Terry Funk in his autobiography. “He always kept his body in great shape and had one of the greatest, most expressive faces I’ve ever seen. I mean, he had the greatest face in the business. It made him a perfect heel. He wasn’t hideously ugly; he just looked like one mean son of a bitch!”

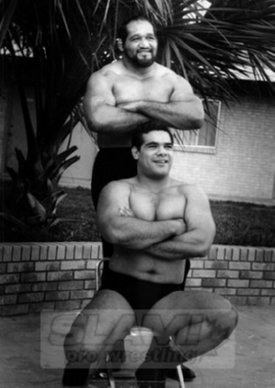

Ciclon Negro and Omar Atlas in Texas, 1968.

Moose Morowski was on the babyface roster for years in Amarillo, and praised his fallen friend. “He was a great worker. We used to go workout at the gym together and he taught me so much. In fact, Cyclone Negro was the one that made the deal for me to go to Australia.”

There were many “Death Matches” against Dory Funk Sr., including one that went FOUR hours in 1973.

Cheryl distinctly remembers that one.

“They both went to the hospital after the match. It was part of the plan. He put Alka Seltzer in his mouth to look like he was foaming,” she said. “When he went to the hospital, it was kind of hard for me to keep a straight face, but the doctor is telling me, ‘We think he might have a broken neck,’ all this crazy stuff. The doctor was facing me, standing in front of the stretcher; my husband was there looking at me, making all these crazy faces that he would make, because even the doctors were fooled that was injured.” When the doctor came back to the room, Ciclon jumped up from the bed, said he was going home, and left the hospital.

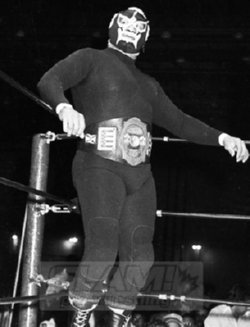

In 1977-78, Cyclone Negro worked in Florida under a mask as “Mr. Uganda” and was managed by Sonny King, and feuded with Dusty Rhodes over the Florida Heavyweight title. “I don’t know what difference it made. Everybody knew Mr. Uganda was my husband,” chuckled Cheryl. “But I guess it made Dusty feel better.”

Ciclon as Mr. Uganda in Florida.

Internationally, there were 23 trips to Japan (where he was Caripus Hurricane), and 20 trips to Australia. Ciclon would hold tons of title belts through the years, including many singles and tag belts out of Houston and Amarillo, Los Angeles, Puerto Rico, Japan, and in Florida. He also got some mainstream publicity appearing on the TV show Lie Detector, hosted by F. Lee Bailey, where he was asked about whether wrestling was fake or not.

Then there were the brass knuckles titles — his specialty. Recognized in Florida, Amarillo and Los Angeles for his pugilistic pugnacity, the belt rests now in a closet at his old home. “He was really proud, because he had been a boxer, so he knew how to throw punches,” said Cheryl.

Cheryl and Eddy met in March 1969, in a Florida convenience store. Cheryl, originally from Kentucky, had taken her disabled sister to the matches, and stopped after the show. Entranced by the beauty, 20 years younger than him, Eddy started following her around the store, singing. Through his rough English, he convinced her to give him her phone number. “He started calling me. He didn’t really talk a lot, but he would sing to me. It was very cute,” she said.

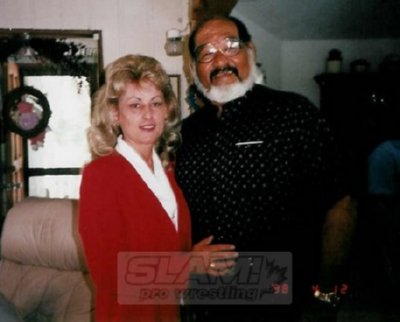

Cheryl and Ciclon.

The couple would have one daughter, Sherri Rodriguez-Jones, and the six kids from Rodriguez’s, to Gladys, would come and go from their lives. Michael lived with them on and off until he was 12 years old, and then Eddy went to court and got full custody of him. “He lived with us until I sent him off to the University of Alabama,” recalled Cheryl. Michael played football for the Crimson Tide, and then made the NFL until a knee injury sent him in another direction.

Rodriguez made sure his second family stayed close, until they settled on a plot of land in Florida and built a house.

“He was really adamant about wanting us to travel with him,” said Cheryl, listing homesteads in Canada, and both Australia and Puerto Rico twice. “It was hard. Our daughter started school in Australia, first grade. But yeah, there’s hardships involved, but at the same time, we’re together.”

It was a complicated extended family, admitted Cheryl. “Just family problems. I was younger than him, and that was the beginning of them not liking me. Over the years, they would visit. The two boys and I got along great.”

Ata Maivia — The Rock’s mom — met Ciclon in the later 1960s in California, when she lived there with her husband Rocky Johnson. Though they kept their socializing to backyard barbecues, because of the heel-babyface dynamic, Ata said that she got to know Rodriguez pretty well.

Though his English was never that great, and there was a thick accent to deal with, Ata said that he always was talking about his children.

“He was very funny. He loved to talk about my Dad, because they were very close friends back then,” Maivia said, referring to High Chief Peter Maivia. As well, Ciclon loved to cook. “He showed me how to do a recipe for chimi-chimi sauce that you put on the barbecue. He was a good cook, good at barbecues.”

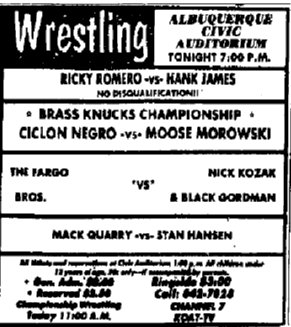

Albuquerque, NM, February, 18, 1973

His wife also raved about Ciclon’s culinary skills, and described the bigger picture. “He was so much more than the wrestler. Especially in the later years, like 1982, he got faith, became a Christian — whole new life. He was wonderful. Always kind. Never backstabbed anybody. Didn’t believe in it. Always polite. Helped everybody he possibly could. Excellent singer and chef,” she said. “He could cook anything and just make it delicious.”

His buddy had his quirks, said Atlas. One day, Ciclon awoke and there was no bread. He confronted his wife, Gladys, and asked why there wasn’t any. She said that he hadn’t given her any money to buy bread. “He was like that with little things, but the next day, he bought a new car with cash,” he chortled.

Rodriguez, Atlas and Jose Rivera teamed to try to promote in Venezuela at the end of the 1979s. “We tried to bring alive the professional wrestling, but it was kind of late, and we don’t have the money that we needed [to pay off the officials],” said Atlas.

The financial failure drove a rift between the two old friends. “We lost the money and she blamed me,” Atlas said of Cheryl Rodriguez. “He probably told her that it was my fault!” This was her husband’s only attempt to promote, said Cheryl, confirming Atlas’ story.

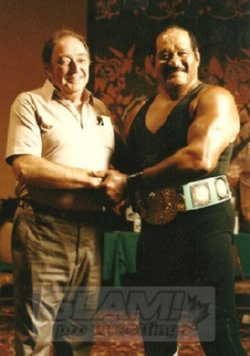

Burt Baum and Ciclon Negro, circa 1984. Photo courtesy Howard Baum

There were a number of times when Ciclon was involved behind the scenes, though, as a booker or talent scout. He helped bring Mario Milano from Australia and Benji Ramirez (a.k.a. The Mummy) from Colombia to North America, and served as the matchmaker for the World Wrestling Alliance promotion run by Burt Baum and Tyree Pride in Nassau, Bahamas and Miami in 1984-85.

His last fling with pro wrestling could have gone much worse. In 1988, Ciclon was hired by a promoter in Australia to help run shows in Yugoslavia. In the country already, the wrestlers had to hightail it out as a violent Civil War erupted around them.

Rodriguez was predeceased by two of his children, a daughter who passed 15 years ago, and a son, Ramon Jr., who died in September 2012. “I didn’t even tell him,” admitted Cheryl.

Tommy Tsuruta, Harley Race, Ciclon Negro and Gordon Nelson in 1973.

He had battled countless health issues for more than a decade. It started with an accident while at work as a welder where he broke his hip; Replacement surgery followed in March 2003. In 2006 he became very ill and while in ICU at the hospital was diagnosed with COPD, congestive heart failure and dementia. The COPD was from the fumes from the welding rods, which had destroyed his lungs.

“The dementia was caused by severe head trauma,” said Cheryl. “The team of doctors could not understand how his brain had so much damage until I told them he had been a boxer and wrestler. He had many stays in the hospitals and countless visits to doctors and he did not want to die in a hospital with strangers around him.”

Ata Maivia kept in touch with the family, one of the few that was allowed to; she invited them to many wrestling functions over the years, but was always turned down. She has nothing but praise for Cheryl. “He adored her, and she took care of him towards the end. He was bedridden for a number of years.”

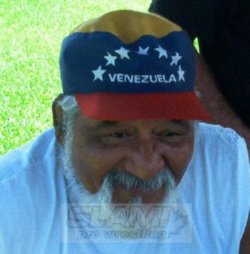

A recent photo.

Initially reluctant to talk about her late husband, Cheryl found confidence in his strength as she revisited the past.

“My husband broke all of his fingers at different times, and he never had them set. He would just throw some tape around them and say, ‘No, no, they’re okay,'” she recalled.

It was hard watching him fade away, though he always remembered who she was, even if he couldn’t recollect what he’d had for lunch.

“When he got really sick in August 2006, the night we took him to the emergency room, he was there for hours and they ran tests. They wanted me to sign a do not resuscitate order, because they didn’t think he’d make it through the night. That was six and a half years that he still lived.”

Ramon Eduardo Rodriguez was cremated and many years down the road, Cheryl has made arrangements to be with her love again.

“Our best years, I will say, were after he quit wrestling and we lived a normal life.”

— photos courtesy Cheryl Rodriguez, unless otherwise noted; thank you to Scott Teal for scanning the images

This story simmered for a long time, but the payoff is great. Kudos to Ricky Johnson for keeping me moving on it.