Bruno Sammartino had said he was done traveling to fan fests and conventions, but then the opportunity came up to be a part of WrestleReunion this weekend in Toronto. Though many don’t know it, Toronto promoter Frank Tunney was key to Sammartino’s fortunes. In short, if it wasn’t for Tunney and his Toronto-based promotion in the early 1960s, Bruno Sammartino would likely never have been, well, Bruno Sammartino.

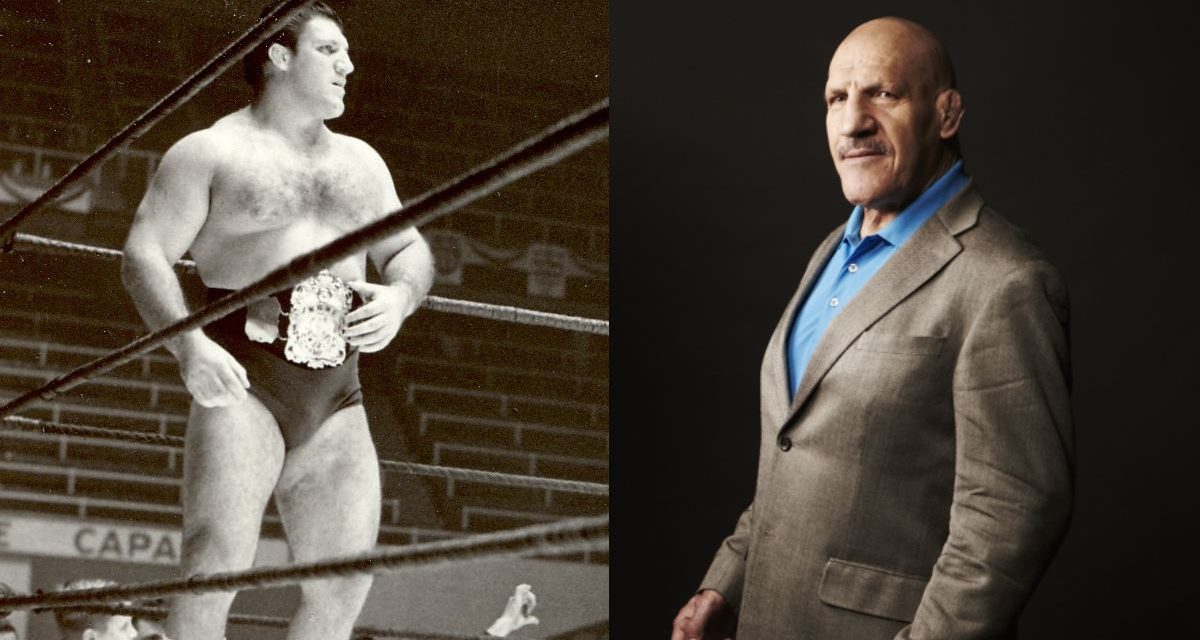

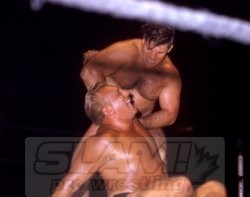

Bruno Sammartino, as WWWF World champion, makes an appearance in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. Photo by Roger Baker.

And loyalty is a big part of Bruno Sammartino.

“The reason that I agreed to do Toronto, because I retired, I won’t travel any more to other cities, I want to come to Toronto because I have the memories, the appreciation, the respect for Tunney and his organization,” Sammartino told SLAM! Wrestling from his home in Pittsburgh. “I just thought, ‘Gee, I’ve never appeared there.’ I’ve appeared all over the country making these guest appearances, autograph sessions and what have you, but never in Toronto. I thought, ‘My goodness, now that I’m retired all over, this opportunity came up where I was asked to come up there. I’ve got to do one shot in Toronto.'”

While the world naturally associates Sammartino with the World-Wide Wrestling Federation, running in the northeastern United States, where he was WWWF World champion two times for 11 years, it was in Toronto, with its wide-reaching television that went out across Canada that he first became a star.

To understand how he got there, a quick history lesson is necessary.

Sammartino was born in Pizzoferrato, Abruzzo, Italy on October 6, 1935, the youngest of seven brothers and sisters. The Second World War was decimating to the family. The family hid in the mountains nearby, with his mother sneaking into town for food.

“I was among the lucky ones that survived because many of our people did not,” Sammartino said. “Because I’d lost a brother and a sister, my mother swore that she was not going to lose another child. And we survived because of her love and care that only a mother can give a child.”

“To make things even worse to show you how lucky I’ve been in my life, I came down with rheumatic fever. The war didn’t kill me but the disease almost did.”

In 1950, a sickly Bruno Sammartino made his way to the United States. Through sports, especially weightlifting, he built himself up into a massive physical specimen, 6-foot-1, 280 pounds.

Spotlighted on a Pittsburgh TV show, hosted by Bob Prince, the voice of the Pittsburgh Pirates, Sammartino was seen that day in his hotel room by Rudy Miller, who worked for Vince McMahon Sr. The next day at the Pittsburgh wrestling TV taping, Miller started asking around about Sammartino. A friend of Bruno’s from high school happened to be working there, and was asked to pass on word that he should come by the studio the next week.

The following week, Miller asked Sammartino about his wrestling background — he used to workout with the University of Pittsburgh wrestling team — and his weightlifting. Miller offered him a chance in that first meeting to head to Washington, DC, to become a professional wrestler.

Bruno Sammartino signs an autograph. Photo by Roger Baker.

“I took time off from work, because I was working a construction job in Pittsburgh, we were building a Hilton hotel at the time. I went to Washington, and that’s where I met Toots Mondt and Vince McMahon. They looked me over, they asked me a lot of questions. Then they took me to a gym and they had me work out with a guy,” Sammartino reflected. “I didn’t know anything. I just went and wrestled with my wrestling experience that I had. Nobody told me anything upfront so I went and just wrestled. I did pretty good, I did well. They asked me, they said they would like to train me. They thought that I could do well. They made me these promises and I said okay. That’s how I got in.”

In Washington, Sammartino worked out with the likes of Jack Vansky, Cowboy Bradley, Angelo Savoldi, and Arnold Skaaland — “New York guys.” In October 1959, he made his pro wrestling debut.

Within a few months, he had graduated from the smaller cities to New York’s Madison Square Garden, and other key northeast cities like Boston and Philadelphia.

“They were making a fuss about me. I wrestled Calhoun, and nobody had ever picked up Haystacks Calhoun, and I picked him up in Madison Square Garden. It was not the main event, it was just one of the matches on the card, but my God, the roof almost flew off the building the people went so wild,” recalled Sammartino.

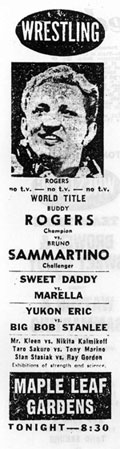

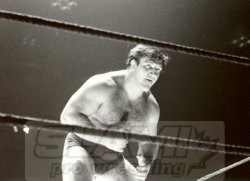

Bruno Sammartino has control of Buddy Rogers. Photo by Roger Baker.

There were politics going on behind the scenes that Sammartino was not privy to.

“I thought I was on my way, on my way to stardom. Instead I started finding myself down more and more,” he said. The reason? “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers his crew of wrestlers were in the territory and became the focus of the promotion. “They became the featured people and I was just a guy on the card. When I spoke up, they thought I was a wiseguy. I gave my notice.”

Unbeknownst to Sammartino, he was doublebooked in Baltimore and Chicago while he was on his way to wrestle in San Francisco to work for Roy Shire. The missed dates led to a suspension in the WWWF-run states, and other states, like California, usually honoured suspensions. After only a couple of dates in California, Sammartino went to Indianapolis on the suggestion of promoter Johnny Doyle, who was working with Shire. There was no state athletic commission in Indiana for one thing.

“I guess Johnny Doyle thought I’d be okay. Unfortunately, some of these promoters, those that were on a friendly basis, they got a call in Indianapolis. They gave me the royal treatment by giving me maybe once a week, a TV show where you’d get paid $25. I couldn’t survive,” Sammartino said. Shunned by the Indianapolis power brokers, Jim Barnett and Balk Estes, he went home.

“I bounced around and everywhere I went, the doors were closed to me. That’s when I finally couldn’t afford to be on the road. I was broke. I didn’t have anything. Finally, I made my way back to Pittsburgh, and that’s where I called up this old contractor I’d met and I got a job in construction. I’d lost my apprenticeship as a carpenter. I got a job as a laborer,” he confessed.

When wrestling was on in Pittsburgh, Sammartino went down to see some old friends. It was Yukon Eric who told Sammartino to try up north. “He said, ‘You ought to go to Toronto. There’s a lot of Italian population and Frank Tunney is a real nice guy.'”

It was a leap of faith for Sammartino.

He made the call to Tunney, and expressed his concern about the blackballing crossing the border. “You don’t have to worry about a phone call. You come here, you keep your nose clean, and there willl be no problem. You will have your opportunity,” Tunney told Sammartino.

Toronto promoter Frank Tunney checks out the action at Maple Leaf Gardens. Photo by Roger Baker.

“I was very concerned. Frank Tunney, I had never met him before. Was I going to get a break there? Did I quit my job and take a chance? Will Tunney get a phone call from somebody in New York, and I’d be right back unemployed again? So I had all these things on my mind, and that’s why, in the very beginning, when I first went to Toronto, I didn’t really think so much about finding out about Toronto. I was too concerned about what was going to happen with me there. But as time went, it became a different ballgame. Once I felt comfortable that Frank Tunney was a very honorable man, and I had a talk with him, and he was going to give me a real opportunity, then I felt more relaxed and I became more interested in Toronto and my surroundings.”

The Italian community in Toronto was significant, and Sammartino capitalized.

“That’s where I helped myself a lot, I think, and I’ll tell you what I did. When I came to Toronto and started feeling comfortable that Frank was going to give me a bit of a chance, I contacted the Italian press. I was cocky in a sense, I contacted them and said, ‘Look, I’m from Italy and I’m here in Canada now. I’m one of the world’s strongest men and I would like to show you what I can do, if you can meet me at the YMCA’ — it wasn’t far, it was walking distance from the hotel — ‘and I want to show you what I can do.’ I really bragged a bit, ‘I can do stuff that not many people in the world can do.'”

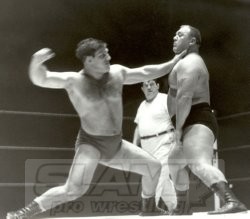

Bruno Sammartino slugs Bulldog Brower. Photo by Roger Baker.

The Italian newspaper came out, and Sammartino did some of his regular routine for them: “I did five reps with 500 pounds on a bench, I did a 750 full squat for them, I did a 350, or 375, military press. So I did some pretty big lifts for them, and they were very impressed.”

Dubbed The Italian Samson, he also got on an ethnic television station, doing feats of strength, like pushups with people on his shoulders, bending a steel bar, or ripping a telephone book.

“I made a lot of them curious, so they started coming to meet this young Italian strongman,” he said. “That all helped. I self-promoted a bit. I think it helped out, because as more and more of them start coming to the arenas, naturally it would make Frank very happy. Frankly, when I first came up there, wrestling was pretty dead. They weren’t drawing at all. I don’t know what had happened, I didn’t know the history. I had heard years ago that it was a very good place to be wrestling-wise. As it happens often in different territories, they have periods where things really go down. There usually was a reason for it. I never knew the reason for Toronto to be the way it was, because it was pretty dead. The Maple Leaf Gardens, my goodness, I was shocked the first time I wrestled there how few people were there. Same thing with places like Hamilton and Kitchener and Welland. I thought, ‘Oh my.’ And Guelph. … More and more people kept coming, more and more people kept coming. We started doing some pretty darn good business back then.”

Bruno Sammartino and Ray Gordon in London, Ontario. Photo by Terry Dart.

The Toronto territory consisted of the major cities of Toronto, Hamilton, Kitchener, London, Kingston, getting regular wrestling, with slightly smaller cities like Brantford, Oshawa, Guelph, and Welland getting frequent shows. Cards often moved outdoors at baseball stadiums during the summers. From Toronto, none of the cities were more than four hours away.

“Toronto is a very interesting city. … I liked the city itself. I liked Maple Leaf Gardens, which we used to go to every two weeks. All the other towns we wrestled in were not far, Hamilton, Kitchener, London was a little further, Port Credit — all these towns, so it made for, as far as I was concerned, a really good place to be,” Sammartino said. “The trips weren’t all that long and the city was good, it was nice. There were decent restaurants and all that kind of stuff.”

During his time in Toronto, Sammartino lived in the Prince Carlton Hotel, near Maple Leaf Gardens. “It sounded like a really nice place … but at the time I was staying there, believe me, I think I was paying, if I remember correctly, I think I was paying $17 a week. So you know what kind of a hotel it was. But it was all I could afford at the time. I had gone through some really hard times, so I had no complaints about being there — because I could afford to be there until I got on my feet a little bit.”

Since he didn’t have a car in Toronto, Sammartino relied on those feet, the kindness of others, and the bus.

“My routine would be the same. I would get up in the morning. I would go to a local place around the hotel, half a block, or whatever, and have a breakfast. Then from there, I would walk to the gym,” he said of the YMCA on College St. “I would always spend about two and a half, three hours working out in the gym. When I got out of the gym, I would get a little rest and then go find a place to eat. Then I’d just hang out in the room, because in a couple of hours it would be time to go to whatever town I was wrestling in. Frank Tunney’s office would be kind enough to arrange a ride for me, and I’d go to the arena. When I’d come back, same routine, get a quick bite to eat, go to bed.”

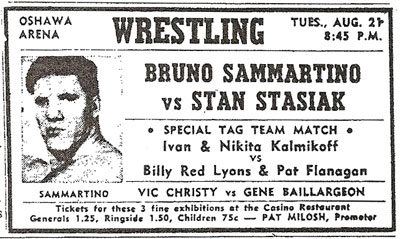

Sammartino in Oshawa, Ontario, August 21, 1962. Courtesy Maple Leaf Wrestling – Pictorial

Every two weeks, he would head home to Pittsburgh. “We usually wound up on a Saturday wrestling in Welland. Then from Welland, usually I’d get a ride to Buffalo with Yukon when he was on the card — most of the time he was. I would go to Buffalo with him, and he would drop me off at the bus station because there was a bus leaving at midnight. It made about six, seven stops, I don’t know, ’til it got to Pittsburgh. When I got to Pittsburgh, then I would get a cab and go home and have a day off. Then the following day, I’d fly to Buffalo and get a ride back to Toronto.”

Fortunately, the travel was a lot more straightforward once Tunney started getting requests for Sammartino across the country.

“The TV was going all over Canada. As I got established pretty well, then of course, Toronto was headquarters, but Frank was getting calls from other promoters and I’m finding myself going to Winnipeg, Calgary, Montreal, Quebec City, all over, different parts of Canada,” he said, explaining that he didn’t really get to know the local promoters, except Eddie Quinn in Montreal a little. “Anyplace I went, I never enquired. I was just there because Tunney sent me there … I’d be at the arena and somebody would tell me who I was wrestling with and what match I was on. I never asked, ‘Is this guy partners with Frank Tunney?'”

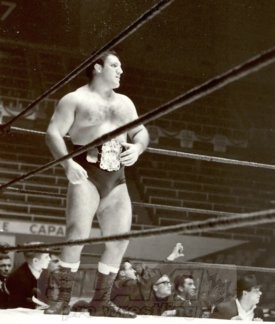

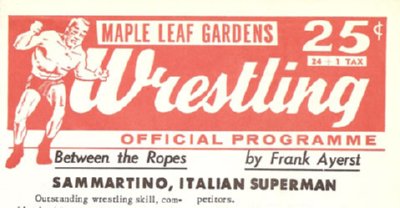

A Maple Leaf Gardens program from 1964. Courtesy Maple Leaf Wrestling – Pictorial

The offices for Tunney’s Queensbury Athletic Club were at Maple Leaf Gardens. Sammartino said that Norm Kimber and Jack Tunney (Frank’s nephew) “were the two key guys,” and that he often met Pat Flanagan and Whipper Billy Watson there. “[Watson] wasn’t wrestling all that much any, though he was still wrestling. He’d be in the office, but I never really knew or asked what the role was with him in the office,” said Sammartino. The Whip and the Italian Samson would tag team a few times, with the “rub” going both ways, helping Whipper stay relevant and Bruno move up the card. “It wasn’t doing me any harm either. Certainly he was a very established guy. I guess it worked well all around!” he laughed.

It took time for Sammartino to be comfortable socializing with Tunney, but he got to that point.

“As the time went by, after about three, four months, he invited me out,” Sammartino said, recalling a meal in Toronto’s Chinatown. “I got very concerned, to be honest with you, when he invited me there, because I wondered if, oh boy, something’s wrong, or that I’m done. But I knew a lot of positive things had happened. I was hoping that it would be positive.

“When we met for lunch, he said to me, ‘I wanted to have you here for lunch because I wanted to let you know that I’m very pleased with the way things are going. People are really taking to you. You’re working very hard and keeping yourself in great shape. I’m starting to get requests for you from other parts of Canada. I just want you to know to keep going, work hard and you’ll find a home here. You can stay here as long as you like, and I hope it will be a long time, because I think we’re going to do okay together.’

“Man, I left there feeling great. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I didn’t expect to hear any of that.’ I was so pleased. From then on, I thought Frank was the greatest. He was a man of his word, he was a very honorable man. That talk that he gave me, gave me all the confidence in the world that all I had to do was train hard and keep going and be the best I could possibly be, and that everything was going to be okay. That went on for a long time.”

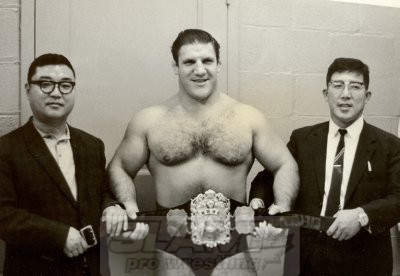

WWWF World champion Bruno Sammartino is visiting in Toronto by some Japanese fans. Photo by Roger Baker.

All in all, though, Sammartino’s time in Toronto — and his bookings across Canada — didn’t last that long. By February 1963, he had mended fences with Vince McMahon Sr. and had committed to returning to the WWWF, where he would dethrone Buddy Rogers for the promotion’s new world title. The WWWF / WWF would be his home until 1988, including being an announcer, and owning the Pittsburgh territory.

He thinks he could have stayed in Toronto.

“I would have stayed. I don’t know how long. Eventually everybody runs out, eventually you overstay,” Sammartino explained. “I’ll tell you why I could have had a real long career in Toronto. I believe I could have been there for years and years for one reason — just like I was in New York for all those years — because Frank’s television was strong, he went all over Canada. I could have kept, staying out of the Toronto office, but not wrestle necessarily all around Toronto. As long as you’re moving around, going to Winnipeg maybe four, five times a year, or Vancouver, out that way. Or even Portland, Oregon, there were requests. Or Quebec. Then in the States, Sam Muchnick was always asking Frank, which later, I made a lot of appearances for Muchnick. When you’re spread out like that and you’re not all the time in the same area, you can last years and years.”

Sammartino welcomes the next foe into the ring. Photo by Roger Baker.

And when the promoter likes you, and you are drawing, it is certainly a feasible scenario.

“Frank had made me feel so tremendously good, was when he told me, if I wanted to make Toronto my home, he says, ‘You’re welcome to stay here as long as you like, because I think you can last here a long, long time.'”

Sammartino stayed loyal to Tunney, even during his days on top in the WWWF.

“I’ll tell you what I did for Frank, because I so respected him, so liked him. He asked me after I took the title in New York, he said to me, ‘Bruno, I wonder if I could count on you once in a while, if you would make an appearance for me at the Maple Leaf [Gardens]. I would appreciate it and it would mean a lot to me.’ I said, ‘Frank, tell me what you want of me. Do you want me every show? Every two weeks?’ He said, ‘I know you want to go home.’ I said, ‘Frank, I owe it to you.’

“For a long time, I went every two weeks back to Maple Leaf Gardens for Frank. I’ll be honest with you, it’s not that I loved it, because I had a home, my parents were old, I had a wife and kid. But I felt like I owed Frank so much because he had kept his word with me a thousand percent. I liked him as a human being. He was a great, great guy. He was just a good, good man. After giving me that break, and I got my break in New York, it really clicked well and everything else, I never forgot what Frank did for me. I did that, in fact, until I broke my neck in 1976. After that, everything slowed down, Frank understood, and I didn’t go no more.”

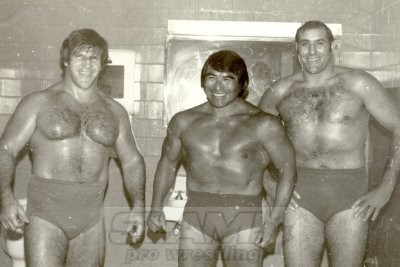

Bruno Sammartino, Luis Martinez and Dominic Denucci. Photo by Roger Baker.

It wasn’t until 1987, when Sammartino worked a WWF show at Maple Leaf Gardens, that he worked in Toronto again. Frank Tunney had died May 9, 1983, and Jack Tunney had taken over and was the figurehead president of the WWF.

For WrestleReunion, Sammartino is driving up from Pittsburgh with Dominic Denucci and a few other friends. He is one of the VIP guests at WrestleReunion, available for photos and autographs. As well, Sammartino is the keynote speaker at the Titans in Toronto 5 breakfast on Sunday, a fundraiser for the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, NY. (This May, Sammartino will be making his first trip to the PWHF, to see Denucci honoured and collect his own ring.)

Bruno named a few friends he is looking forward to connecting with in Toronto.

“I had a lot of great matches with [Sweet Daddy] Siki. Siki was a great guy. There was the Wolfman, Willie Farkus. … It’ll be good to see those guys, and I’m sorry that Waldo’s not there, Von Erich. I had a lot of great matches with him as well.”

RELATED LINK