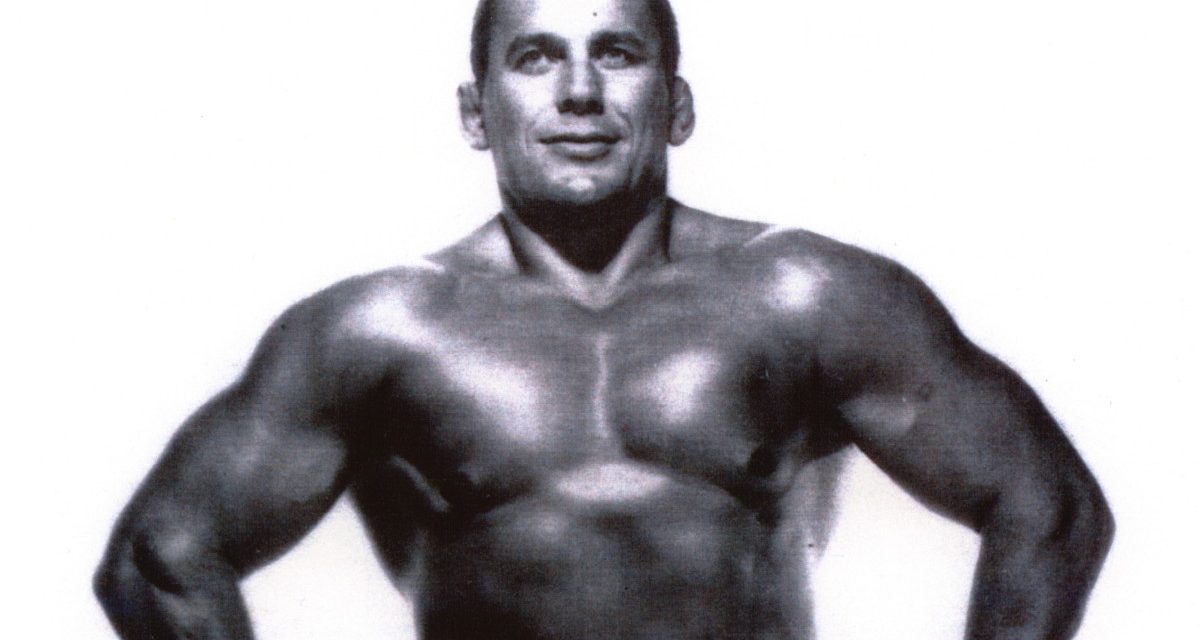

Talking to his peers, it is evident that Edouard Carpentier was a bit of an enigma. No one denies his success in the ring, his incredible, acrobatic talents and drawing power. But Carpentier, who died Saturday, wasn’t universally loved, in part because of his moody, loner personality, but also because of the challenges of working his style.

One of Carpentier’s greatest opponents was Ivan Koloff. “The Russian Bear” put Carpentier in league with the likes of Mil Mascaras and Billy Robinson.

“There were several guys like that who were in right great shape, and they’re the type of wrestlers that you had to be on your toes and work hard to make a match,” Koloff said. “Not that they were difficult that way, it was just the idea that they were proud guys and you just didn’t kick them around in the ring.

“They made you work for it.”

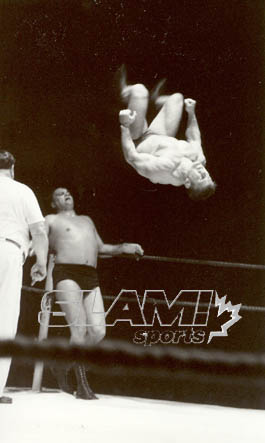

Edouard Carpentier performs a moonsault at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens in the 1960s. Photo by Roger Baker.

“Cowboy” Bob Ellis was Carpentier’s championship tag team partner in California, and one of the few babyfaces of the era that could compare in drawing power.

“I worked on his first card when he was champion in St. Louis, and he’s a nice person,” Ellis recalled, explaining that the fans enjoyed Carpentier’s style. “They enjoyed it, they got a kick, but back then, we were trying to make it look very rough and real, and those flips and flops, that wasn’t the real part. That’s like today. But he was a good worker, he was just so small.”

At 5-foot-10, Carpentier wasn’t that small for the era, but when working main events against giants such as Killer Kowalski and Don Leo Jonathan, there was an obvious size difference.

“Back then, it wasn’t a monster era. You had your occasional big man, like Chuck Connor, who later went on to be John Studd, was up in Montreal with us,” said Sir Oliver Humperdink, whose Hollywood Blonds tag team worked almost a year straight with Carpentier. “But that was the exception rather than the rule. Guys Carp’s size or Maurice Vachon’s size weren’t large men, but they were pretty well the norm.”

In Montreal’s Grand Prix Wrestling in 1972 and 1973, Carpentier teamed often with Jean Ferré, the future André the Giant.

Jerry Brown of the Blonds enjoyed the time with Carpentier. “It wasn’t hard. He was good. He was in shape, I’ll tell you that,” said Brown. “The fans loved him.” Unlike the young Giant, who was always mixing with the crowds and having a good time, Carpentier wasn’t all that visible, said Brown, calling him “kind of a loner.”

That translated throughout most of his life, said longtime friend Hans Schmidt. “He was a good friend of mine, and I feel sorry, but he didn’t have anybody. He was all by himself, and he’s gone,” said Schmidt. “He had a girlfriend, but as far as I know, he never married.”

Humperdink first saw Carpentier when he was a fan of the AWA in Minneapolis, where The Flying Frenchman had a run in the 1960s. Later, Humperdink got to know the star. “He never struck me as moody, but he did enjoy the spotlight, the reaction he got from the fans. A less kind individual might say he was glory happy.”

“The Sensational, Intelligent Destroyer” Dick Beyer met Carpentier in Los Angeles in the early 1960s, and appreciated the big star offering him some advice.

“We were either riding in the car or in the dressing room, he told me one night, he says, ‘Destroyer, you never take the mask off because right now, you can go anywhere in the country and you’re a main eventer. If you take the mask off, as Dick Beyer, you’re going to go in the preliminary,'” Beyer remembered. “That was coming from then a guy who was working on top all over the place, and he’s talking to me in Los Angeles, and while I did work on top prior to going to Los Angeles, in Hawaii and some other places, but Edouard gave me some very good advice at a time in my career when I needed it.”

When they did hook up in the ring, it worked, because Carpentier could do more than just the high flying, said Beyer.

“He did the acrobatics that nobody else did. Ricki Starr did some of the things he did. But Edouard did things that a lot of other people couldn’t do,” Beyer said. “When I looked at him, it was a person that I could wrestle with, because I was a wrestling heel, I was a heel and he did babyface things I could work with as a heel.”

It wasn’t the usual match, though, stressed Dominic Denucci.

“Edouard Carpentier, he could do everything. Edouard Carpentier could have a match with Kowalski that you couldn’t believe. But the heel has to adjust to him — not Kowalski — but the other heels have to adjust to Edouard Carpentier, because he was doing acrobatics,” said Denucci.

Wherever he traveled, and Carpentier traveled a lot for the era, often used as a special attraction on big shows, he was a star. But again and again, the anchor of his career was Montreal, where he started in North America, where he owned 20% of the Grand Prix Wrestling promotion for a time, where he was an announcer, where he was an icon, and where he died on Saturday at the age of 84.

It was there right at the beginning, said Angelo Savoldi, who worked Carpentier’s first match in North America in Montreal at the Forum in 1956.

“I had his first match,” said Savoldi. “He was something like Argentina Rocca, jumping up in the air and all that stuff.”

The fans “went wild” that first match, he said. “I lost to him in about 15 minutes. It was a 30-minute match. In about 15, 16 minutes, he jumped on my shoulder — how the hell he did it, I don’t know — and he rolled me over, and that was it.”

Baron Michel Leone raises Edouard Carpentier’s hand after the Frenchman beat John Tolos for the America’s title at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles in 1974. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

Occasional SLAM! Wrestling contributor Dr. Mike Lano went to Montreal to photograph a major Grand Prix Wrestling show at Jarry Park, the stadium that was home to the Montreal Expos. At that 1973 show, Carpentier teamed with Bruno Sammartino to face the Hollywood Blonds.

“I remember the deafening crowds marking out like crazy for the dramatic face team of Carp and Bruno,” said Lano.

“He just had that ‘it,'” said Humperdink. “People loved Edouard Carpentier, especially in Quebec, Eastern Ontario, wherever our TV went from there. In Grand Prix, people just loved the guy. He was a handsome bastard. He had a beautiful smile and everything. He was a great-looking athlete. He had everything it takes to be popular. And there wasn’t anything he couldn’t do.”

As Quebec wrestling icon Yvon Robert has often been called the Rocket Richard of wrestling, Carpentier was dubbed the Jean Beliveau of wrestling. Whereas Richard had fire and passion, Beliveau had class and dignity.

“He was a superstar’s superstar. They all knew Edouard Carpentier there, no matter what field. Hockey was huge up there, but everybody knew who Edouard Carpentier was. He was a god,” concluded Humperdink. “He was a matinee idol, brother, he had that matinee idol good looks, winning smile. He won everybody over.”

RELATED LINKS

- Nov. 1, 2010: Edouard Carpentier dead at 84

- Nov. 3, 2010: A photographer’s memories of Carpentier

Greg Oliver relishes the days when he can talk to the likes of Angelo Savoldi, Dick Beyer, Bob Ellis and Oliver Humperdink all in one evening.