Pro wrestling announcers have perhaps the most challenging jobs in the business. They are the only ones required to sit at a desk for two or three hours and work from the minute that little red light on the camera goes on, to the second it goes off.

The job is very demanding and requires a lot of hard work, patience and preparation, which veteran announcer Jim Ross cannot emphasize enough.

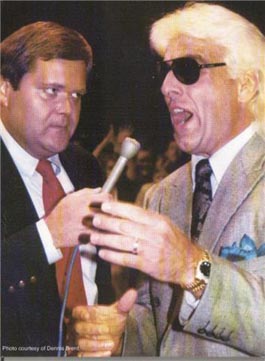

Jim Ross interviews Ric Flair in the NWA. Photo by Dennis Brent.

“I will generally spend several hours the week of the PPV from Wednesday through Saturday preparing and then I lay low the night before the event reading over my notes and of various ways to describe the superstars,” Ross told SLAM! Wrestling. “You will rarely see me ‘out with the boys’ the night before a big event. I have been known as one who perhaps ‘over prepares’ but I like to be mentally ready to do my job and I approached broadcasting football or any other entity the same way. The viewers deserve the best product possible and that means the broadcasters need to carry their share of the water and not get in the way of the broadcast but enhance it with info that they perceive the fans need or want to know.”

Just like any other major industry, the wrestling business is always changing in order to appeal to different generations. All aspects of the business are expected to make those changes, including announcing. And being in the business during the evolution of pro wrestling into sports entertainment, Ross knows this perhaps better than anybody.

“When I first started, I was a wrestling announcer doing play-by-play or hold-by-hold calls, while now I am no longer considered a wrestling announcer and am more of a storyteller,” he said. “From a broadcaster’s perspective, I liked the original play-by-play presentation a great deal but overall the business has improved immensely when one looks at the income the wrestlers are able to earn, the production improvements the TV folks have brought to the table and the global exposure of the product. It’s all about the money and there is more money to be made by more people within the industry than ever before.”

Having several different broadcast partners with several different styles throughout his career, Ross has been able to adjust his own style in order to create great chemistry with everyone he works with. In a business like pro wrestling, not everybody is going to get along, but Ross says it’s important for individuals to pull it together and maintain their professionalism on camera.

“It isn’t imperative that the broadcasters get along off camera but it certainly doesn’t hurt. It makes the team better if partners do positively co-exist as it lends to the chemistry of the team. I have been lucky in that I have worked with some really good guys over the years that all to the man, in one way or another, have made me better,” Ross said. “I worked the longest with Jerry Lawler and we did and still do get along famously. I don’t think that I have ever worked with any one over any length of time that I did not really get along with even though Jesse Ventura and I had some bumps in the road getting used to each other’s style and timing when we first began our partnership in WCW. I hope that Jesse and my work together did not adversely affect any of our broadcasts. I feel like I have done some of my best work while being ‘provoked’ by my partner during a broadcast.”

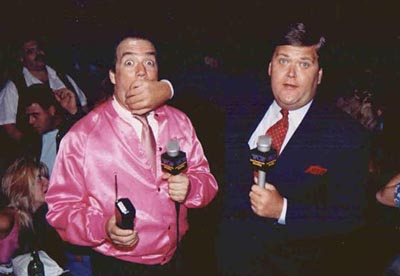

Jim Ross muzzles Paul Heyman in the NWA. Photo by Dennis Brent.

One of those partners Ross speaks of that may have been provocative enough to get the best out of him was Paul Heyman. Heyman was first paired with Ross in WCW in the early ’90s, spending numerous weekends together, as they called The Power Hour on Friday nights, WCW Saturday Night and The NWA Main Event on Sunday nights. He was a master of pushing Ross’s buttons to get him on the edge of his seat. Heyman’s job at the time was to antagonize the host and he feels that he worked best with Ross, because they were able to compliment each other’s personalities and styles so well.

“I learned more about announcing from Jim Ross than I can ever describe. He was a marvelous teacher, because he wanted to be the best, and didn’t want anyone to drag him down,” Heyman said. “So he made sure my game was upped at every level. We both studied our asses off, and critiqued our own performances, and the chemistry was just there. We could just come out and argue in a shoot, but within a worked context about the storylines involved.”

Heyman had the opportunity to work with Ross again in the WWE on Monday Night Raw, as the replacement for Jerry Lawler in 2001. While the environment had changed significantly, the chemistry remained the same.

“Comparing the announcing duties in WWE and WCW is like comparing apples to hockey pucks. During the time I was in WCW, Jim Ross and I produced ourselves. No one really gave us any creative direction. WWE has Vince McMahon’s distinct vision and he gives you direction before, during, and after the show,” Heyman said. “When I was going on the air that first week, the only thing Vince asked of me was to take Jim Ross out of his own comfort zone. JR had worked with Jerry Lawler for seven years, and they had a natural give-and-take. Vince wanted me to figuratively stick a pin in JR’s ribs and make him fight for the babyfaces. Vince wanted a combative Good ol’ JR. I guess Vince didn’t watch the old WCW tapes because that’s exactly what JR and I were like on the air. I liked it when JR would bring the fight to me on the air. I knew I was pushing his buttons. But the job was to always battle each other over the storylines, and we really felt it. He took the position the babyfaces were heroes who were being victimized by the dastardly heels, and I defended the heels as if my life depended on it. That simple formula made for some great on-air arguments.”

Heyman agrees with Ross that chemistry is important for any announce team, but balance is just as important. He’s played the role of the antagonist for most of his announcing career, but it’s a role that really hasn’t been seen in a while. Back then, it was common to have both a protagonist and an antagonist announcer, who would not only grab attention by bickering on-air, but also get the product over in the process.

“I always approached colour commentary as being the heels’ advocate. I didn’t just want to take shots at the babyfaces, which had become the norm. I wanted to present legitimate arguments from the heel perspective as to why this move, this attack, this swerve was justified. I didn’t want to say things heel-ish just for heel’s sake. I wanted to come across like a lawyer presenting the case to the jury,” Heyman said. “Back then, the play-by-play guy called the action, while the colour commentator added the sizzle. Today, the lines are blurred. There are two people announcing the show, with either a supporting analysis or a conflicting analysis. I can’t say either is better than the other. It all depends on the product you’re selling, the point in time, and the announcers involved.”

Announcers rarely start their careers in the wrestling business as announcers. Ross was a referee, Heyman did play-by-play on the Northeast independent scene but was a manager at first when he got to WCW, and more often than not, retired wrestlers will step into the broadcast booth to provide their two cents.

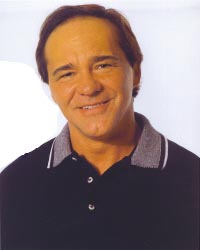

Larry Zbyszko in a WCW publicity shot.

The transition from wrestling to announcing isn’t an easy one. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, it works very effectively. When Bill Watts became booker of WCW in the early ’90s, he took a chance on putting Larry Zbyszko into the broadcast booth as a replacement for Jesse Ventura. And it was a risk that paid off.

“It wasn’t my thing at first. I was a wrestling star. But it didn’t take long for me to get into the groove of announcing and I suddenly realized that I was making more money doing this than wrestling,” Zbyszko said. “When you put wrestlers on camera as announcers, they have to be able to step out of that role as a wrestler and start putting everybody else over.”

Zbyszko wasn’t an announcer for that long, but during his run as an announcer, he understood the roles that each announcer is required to have and it was almost as if he created a completely different personality for himself that had never previously been seen when he was a wrestler.

“The job of the play-by-play announcer was pretty boring and straight forward,” Zbyszko said. “The colour commentator would add the details and fill in the blanks. I would add emotion to the broadcast and explain why a wrestler is doing what they’re doing from a wrestling point of view.”

It’s really hard for a wrestler sometimes to put someone else over. But Zbyszko was able to make the transition quite smoothly. He would sometimes play the antagonist role, but other times, such as when he called Nitro with Tony Schiavone in 1996, Zbyszko remained neutral to change it up a bit.

“I wouldn’t go out of my way to play a heel commentator,” Zbyszko said. “If a commentator stays heel, the broadcast becomes one-sided and isn’t easy to listen to. It turns into a two-hour heel promo, which becomes irritating. I loved doing commentary. It was a great job. I was on television and was getting more publicity than any of the wrestlers.”

Terry Funk was another wrestler-turned-announcer. But the difference between him and others is that he was able to switch between wrestling and announcing so frequently without ever missing a step. In fact, he still had one more run left in him after his stint as an announcer.

Funk enjoyed commentating and remembers working with Chris Cruise in particular, calling WCW Worldwide. Funk says the relationship between announcers is an important one and it shows on the air.

“The key is to have two guys that meld together very well. That’s the real key to the situation; it’s a good team, not a good individual. Really, it’s like a straight man and another guy. It’s Abbott and Costello all over again,” Funk said. “You have to be very spontaneous. You have to have a compassion for one another, so you don’t run over each other. You have to have two guys who are willing to give. It’s very much similar to working in the ring. That’s the truth, announcing a great match is very much like working a great match. You have to have both guys doing their best not to try to bury somebody, but trying to make their partner and do well themselves at the same time.”

Though Funk has never announced in the WWE, he sees it as a completely different playing field than WCW. In fact, Mick Foley, who Funk has been a mentor to over the years has had a run as an announcer for WWE, which didn’t work out. Funk says he doesn’t know if he could have done it either, but overall, he’s enjoyed his run as an announcer and wouldn’t have changed a thing.

“As far as their (WWE’s) announcers are concerned, they trust their judgments better than they do their wrestlers. I don’t think I could have done it. I love to create, no matter if it’s in the ring, if it’s announcing, or wherever it is. That’s the part that’s missing. That’s the part that’s missing from Gordon Solie. Jim Ross, he’s been doing this so long that he can interject his own personality — if they let him. So can Lawler. They’re there, they’re established, and they’re capable of doing more things than what they allow any of them to do,” Funk said.

Some wrestlers are great at cutting promos, so one would think they’d be naturals in the broadcast booth. But it doesn’t always work out that way. After the WWE’s purchase of WCW in early 2001, Scott Hudson was called up for a one-time announcing job on Raw and was partnered with perhaps one of the best talkers in the history of the business, Arn Anderson.

“That first night on Raw was a catastrophe. The match we called between Booker [T] and Buff [Bagwell] was terrible and nothing against them, because they’re great athletes, but it just didn’t work that night,” Hudson said. “As we were leaving up the ramp, I saw Arn backstage and he was covered in sweat. So I went up to him to ask if he was okay and he says, ‘Man, I don’t know how you guys do this every week.’ Coming from a guy who is universally acknowledged as one of the greatest talkers in the business, I took that as a compliment.”

Hudson grew up as a fan first and foremost, so he certainly had an unbridled enthusiasm and passion for the product, which is essential in adding to the success of a broadcast. His most popular run as an announcer came in the late ’90s, when he was working in WCW, calling Nitro with Tony Schiavone and Mark Madden. He really enjoyed being part of the team.

“The key to having a great announce team is for everybody to know their roles. One guy is the play-by-play guy and is responsible for keeping the story moving and keeping the audience entertained, while also selling pay per views,” Hudson said. “Tony was the anchor that carried the broadcast, I was in charge of calling the action in the ring and Mark injected the colour.”

Scott Hudson while in TNA.

In its later years, WCW was famous for having multiple-person announce teams, which as Hudson would occasionally discover, can be very difficult for everybody to get a word in.

“I found that it really hindered the broadcast,” he said. “There are just too many voices out there and it was hard for everyone to keep their egos in check, but we all liked each other and were very appreciative and respectful of each other’s skills, so we were able to co-exist.”

In wrestling, a great announcer is a great announcer, but Hudson says that sometimes the most effective way to put over a certain angle or segment is to say nothing.

“Whenever a special ‘moment’ happens in wrestling, you really don’t have to say anything, because the visual is enough,” Hudson said.

Hudson was a member of the WCW announce team in its later years, but Chris Cruise called play-by-play for WCW in what may have been the company’s glory days. Cruise was usually paired with wrestlers who made the transition into commentary, and he had a great time, despite the fact that the actual product was not always as great. Cruise specifically remembers being paired with Dusty Rhodes and Larry Zbyszko, calling WCW Pro and WCW Prime, as well as a show on Saturday mornings.

“My job as an announcer was to produce good and entertaining television,” Cruise said. “But I would never try to outshine the actual match that I was calling. Sometimes I would call matches with Larry Zbyszko and Dusty Rhodes and some of the matches were just awful. So in those cases, I would try to make the most of it and do my best to make chicken salad out of chicken shit.”

Cruise was calling matches at a time when the protagonist/antagonist relationship still existed. He always tried to get along with all of his partners and enjoyed many of his broadcasts.

“The two members of an announce team have to genuinely like and respect each other and respect each other’s talents and passions as well in order for the team to work,” Cruise said. “Back then, there was a face announcer who always remained neutral and then there was a pro-heel colour commentator. Now, it’s migrated into complimentary storytelling.”

Much like Ross, Cruise was very adamant about preparation before a broadcast. He worked a lot of shows throughout his announcing career, but perhaps his most famous broadcast was in 1994, when he called a pay per view for AAA called When Worlds Collide. That night, Cruise was working with a relative new-comer to the business named Mike Tenay. It really impressed Cruise that night to see how well prepared Tenay was.

“I don’t think there’s enough preparation that announcers do before a broadcast, which really bothered me. Some announcers would just want to go out and wing it on the air, except Jim Ross,” Cruise said. “It’s the easiest thing in the world to call the moves, but it’s really tough trying to tell a story the way Jim Ross did it. I traveled to Mexico and I didn’t really know anything about that style of wrestling. But Mike had prepared background notes and history for us to use and I was very impressed. The atmosphere that night was simply electric.”

The job of an announcer in pro wrestling is not an easy one. Every comment has to be timed perfectly, right down to the minute. And even though that classic relationship between protagonist and antagonist announcers has disappeared, the memories still live on.

“Back in the day when I started, 1974, the play-by-play guy was largely a ‘homer’ for the fan favourites while the color commentators, often times the promoter or a more neutral representative, eventually morphed from objective ‘analysts’ to siding with the villains,” said Ross, who blogs and promotes his restaurants at jrsbarbq.com. “The play-by-play announcer called the running commentary including holds and predicaments while the colour commentator explained the holds and how they functioned while adding some ‘sizzle’ to the steak. The first ‘bad guy’ that I worked with extensively was Freebird Michael Hayes who was an excellent antagonist and who, occasionally, legitimately got under my skin which raised the tension and realism of our broadcasts.”

— with files from Greg Oliver