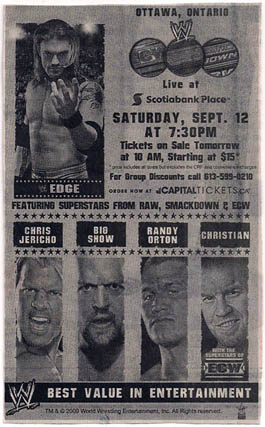

The news that the WWE is setting up its ring at Scotiabank Place in Ottawa on September 12 for a gala show featuring stars from Raw, Smackdown and ECW may seem like a big deal to present day wrestling fans but top wrestling shows were the norm in the nation’s capital over a half century ago when the biggest names in the business showed their wares at the old Ottawa Auditorium.

As a hot venue, Ottawa has been somewhat out of the loop lately when major shows have been booked on the Canadian tour. But all eyes will be on the reaction to WWE’s latest foray back into the capital city with stars such as Chris Jericho, Edge and Randy Orton slated to appear.

I don’t know all the reasons why Ottawa is not considered a regular stop on the McMahon circuit because the city has a rich history in professional wrestling dating back to the 1930s when weekly shows were held at the Aud.

The arena was located at the corner of O’Connor and Argyle streets in downtown Ottawa primarily for hockey and to accommodate the NHL Ottawa Senators. It opened in December 1923 and hosted the Senators until the franchise relocated to St.Louis in 1934. The arena was egg-shaped with semi-circular end boards unlike the normal orthogonal shaped rinks.

Pro wrestling became a regular staple on the arena’s schedule and attracted top names from the outset including a bout between former champion Dick Shikat and the villainous Howard Cantonwine in August 1932. From that point on the grapplers became a fixture at the Aud and local sports fans got as much excitement from the grunt and groaners as they did from the hockey fights at the arena. When the ring was set up at centre ice the only thing peculiar about the arena was the never ending list of mat maulers that paraded through the building. They came in all shapes, sizes and colours and the rapid fans from both sides of the Ottawa River loved it.

The Aud was a regular stop on Eddie Quinn’s circuit operating out of Montreal. Quinn had been promoting in Canada since 1939 and built up a loyal following for his shows at the Forum among other venues. Throughout the 1930s, some of the Ottawa regulars were Yvon Robert, Canadian Olympic hero Earl McCready, Ed “Strangler” Lewis billed as the NWA champion, Ed Don George, Sandor Szabo, Rudy Dusek, Wild Bill Longson and Jumping Joe Savoldi.

Since Quinn promoted throughout Quebec, and the Ottawa-Hull region was bilingual, it was a foregone conclusion that fans would flock to see francophone stars. To this end, Robert was groomed as the headliner and Ottawa fans easily identified with the star. Larry Moquin was given a push but never quite attained Robert’s popularity or status with fans.

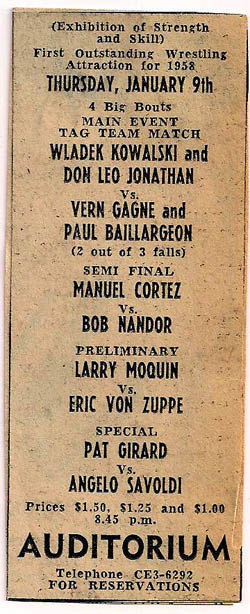

Wrestling survived in Ottawa during the 1940s and names such as Lou Thesz, Bobby Managoff, and Ben Sharpe became familiar to locals. But with the advent of television and the modernization of the game, the 1950s proved to be the most interesting and exciting at the Aud. During that decade, all the big names came to Ottawa and all the angles were played out.

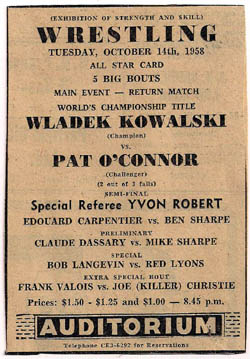

Many bouts were listed as championship matches from as far back as the 1930s when Strangler Lewis and later Ed Don George were billed as NWA champions. In a match in 1947, Managoff beat Thesz for what was listed as the AWA title and two years later Thesz and Robert squared off in a no contest affair for the NWA crown. In the early 1950s, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers was AWA champ and successfully defended against Sammy Berg, the former Canadian Olympic swimmer turned actor. Wladek Kowalski was billed as the district champion in his battles with Pat O’Connor.

Whether any of these championship matches were legitimately sanctioned by the respective wrestling organizations or whether the participants listed as champions were recognized elsewhere in the wrestling world is a debating point for wrestling historians to resolve. The main point is that the Aud featured many such championship clashes with top notch performers.

Fans in the Ottawa area were always enamoured of all the great mat stars but because of the large francophone population in both Ottawa and Hull and surrounding area, they gravitated towards the French-Canadian stars. By the late 1950s, their hero, Yvon Robert, known as the Lion, was winding down a glorious career. Johnny Rougeau was now appearing in main events while Larry Moquin was working mostly on the under card.

Other big names under the lights at centre ring, in addition to Thesz, Managoff and Rogers, were Wladek Kowalski, Manuel Cortez, Yukon Eric, “Honest” Johnny Valentine, Don Leo Jonathan, Bull Curry and The Baillargeon brothers, Paul, Adrien and Tony.

Formidable tag teams such as Gene and Steve Stanlee, Omaha’s riot squad of Ernie and Emile Dusek, and the treacherous Great Togo and Tosh Togo battled the best babyfaces in the business.

As any true wrestling fan will attest, the workers on the undercard are vital to the success of any show. There were a never-ending supply of wrestlers in this role including Frank Valois, Eddie Auger, Legs Langevin, Billy Red Lyons, Sammy Berg, Rebel Bob Russell, Ovila Asselin and a young French-Canadian roughneck named Maurice Vachon who was still a few years away from main-event billing.

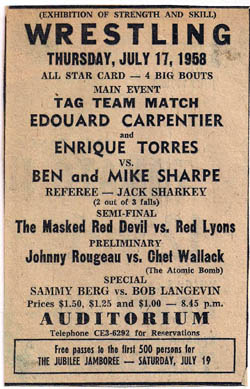

But promoter Quinn hit the jackpot when he brought in Edouard Carpentier in the mid-1950s. With Robert’s career at an end and Rougeau not quite ready to carry the shows, Carpentier was an instant hit, not only in Montreal but also at the Aud where he became a regular visitor.

Throughout the decade there was a never-ending string of matches that provided fans with unending excitement. There was always a grudge going on in some form or another. Even though the Aud was a 7,500 seat arena, the wrestling shows only attracted several thousand fans unless there was a really big feud in progress or some special event. For instance when Yukon Eric and Wladek Kowalski battled to a draw in January 1952, it was just another match. Had it been scheduled after the famous “ear” incident, it would no doubt have been a sellout.

By 1957, Edouard Carpentier was billing himself as the NWA champion although there was some dispute over the claim. Fans became accustomed to nothing ever being black and white in the wrestling game unless of course it was an unruly no-contest between Bearcat Wright and Dick the Bruiser. The pair met in a season ending show at the Aud in December 1957 on a card that saw Carpentier successfully defend his title against Dangerous Danny McShane.

The popular Carpentier also lined up with Verne Gagne to take on the unruly brother combination of Mike and Ben Sharpe. That year also saw the appearance of Pat O’Connor, Enrique Torres and strongmen Paul Anderson and The Mighty Ursis.

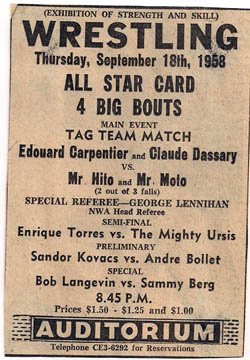

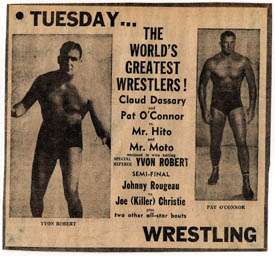

Tag team wrestling was always popular at the Aud and two of the best heel teams on the circuit in 1958 were the Sharpe Brothers and Mr. Hito and Mr. Moto. Promoters never had any difficulty in lining up willing opponents for the hated teams.

Mr. Hito and Mr. Moto took up where the Togo Brothers had left off earlier in the decade and with their patented sleeper holds, salt throwing and sneaky maneuvers were difficult to beat. Johnny Rougeau and Pat O’Connor had a lengthy feud with the duo and after three rematches finally jilted the Japanese pair with the aid of special referee Jack Sharkey and a ring enclosed with chicken wire. This was in an era long before steel cages.

Edouard Carpentier took up the battle against Hito and Moto first with Rougeau as a partner and then with Argentine (Antonino) Rocca. Rocca and Carpentier came out on top with the aid of British Empire Light-Heavyweight boxing champion Yvon Durelle as referee.

Promoter Quinn always tried to capitalize on the francophone angle in Quebec and Ottawa and ensured his shows featured that French presence. At least in name, since what you saw was not always what you got. A face named Claude Dassary was brought in to team with Carpentier against Hito and Moto and also hooked up with Pat O’Connor against the Japanese force. Dassary even went alone against the pair in a losing cause and soon became an Ottawa favourite. Not many fans were aware that Monsieur Dassary was actually Alfonso Carlos Chicharro from Spain who later went on to greater fame as Hercules Cortez.

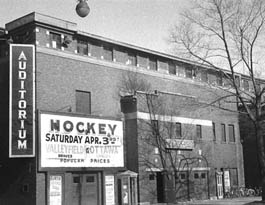

A more recent advertisement!

Mike and Ben Sharpe, a burly pair from Hamilton spelled off Hito and Moto as number one tag team heels and faced the same line of opponents that the Japanese pair had feuded with. Carpentier opposed the Sharpes with various partners including Rougeau, Enrique Torres and Tarzan Zorra. Different names, different partners, same results when the grudges were milked for maximum profit and the patience of the fans was tested to the fullest.

Unlike today, fans were often involved in the action at ringside. When a popular hero like Carpentier was getting ganged up on in the ring, it was not uncommon for fans to come to his rescue. Some carried boards to even the odds against the bigger wrestlers. At times the fans threw bottles at the referee and villains and the bouts were stopped. The angry spectators chanted “we want our money back,” and refused to leave the arena until ordered to do so by city police.

All the while, promoter Quinn counted the gate receipts and planned for next week’s show. One of his favourite lines was: “The only thing on the level is mountain climbing.”

Mike Denihan was a young impressionable teenager playing hockey in the Ottawa city junior league in the 1950s. He had many opportunities to hang around the Aud between games and after practices. Originally from Renfrew, Denihan was a fierce follower of wrestling and grew up watching his boyhood idol, Larry Kasaboski battling villains in his hometown.He was at the matches at the Aud on one occasion sitting close to the runway. As the wrestlers were introduced for the match, suddenly he heard a voice from behind him. “Hey kid, get out of the way or I’ll tear your head off,” someone growled. Another voice echoed a similar threat: “Yeah, I’ll kick your head in.”

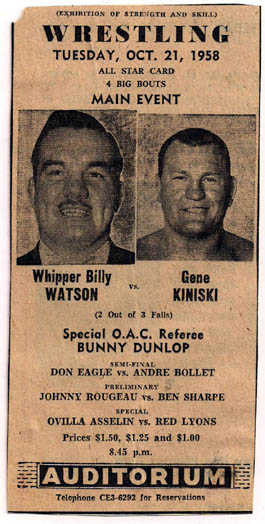

Denihan recalls the encounter to this day. “I thought it was someone who was upset over the way I played hockey. When I turn around… there’s Gene Kiniski and Killer Kowalski. They looked huge. Of course I moved and when they ran by, Kiniski growled. “You better cheer for me.” Denihan affirms that he did cheer for the hated villains that night.

Kiniski and Kowalski went on to become two of the biggest stars in the game. Mike Denihan became a hockey star with Boston University.

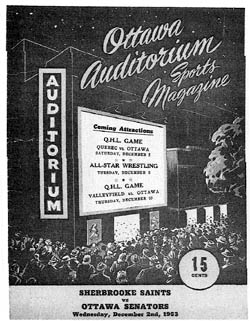

A junior hockey program.

On occasion, to add spice to the Ottawa lineup, big names from the Frank Tunney promotion in Toronto appeared. British Empire champion Whipper Billy Watson successfully defended his belt against his old nemesis Kiniski and in a battle of science also tangled with Carpentier.

The Ottawa Auditorium was home to junior hockey as well as wrestling. Photo by Ivor Thomas, 1953.

When it came to pro wrestling, Ottawa fans didn’t miss too much. Even in a sleepy government town where the 11 o’clock curfew sometimes brought the main event to a halt, the fans returned the next week for the rematch. They were hooked. Reports in both the Ottawa Citizen and the Ottawa Journal kept wrestling fans abreast of all the shenanigans down at the old egg-shaped Aud.

The Ottawa Auditorium closed for business after the last attraction was held on October 1, 1967. Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians had the distinction of bidding Auld Lang Syne to the fabled old arena. No doubt, many of the patrons danced to the music just as the professional wrestlers had danced through their paces in the ring at centre ice.

When the WWE stars head out to Kanata in September, many of them will not even be aware of the rich history of their profession in Ottawa.

But rest assured that even though the Aud has long since disappeared, the many memories from the mat a half century ago will remain a part of wrestling folklore in Ottawa forever.