The year is 1980. Screaming fans would fill arenas all over the Mid South. They travelled from Oklahoma to Arkansas to Louisiana to Mississippi and back again. They didn’t mind the uncomfortable seats, the heat, the humidity or even the dimly-lit arenas. The only thing that mattered to them was the sight of two guys standing in opposite corners of the ring, with looks of pure hatred in their eyes. After the show was over and the wrestlers returned to their individual locker rooms, the fans were already buzzing with anticipation of the next event, leaving promoter Bill Watts smiling from ear to ear, because he had done his job right.

Watts marketed pro wrestling as a legitimate sport in those days. He wanted fans to think of it as real as boxing was. Not only would the heels and the babyfaces dress in different locker rooms, but they would not even be seen together in public. Breaking kayfabe at that time was blasphemous.

Cowboy Bill Watts as a wrestler.

While the action in the ring may have been pre-determined, the emotion displayed by the audience was as real as it gets. Watts could make them laugh, cry, cheer, boo, and more. With every show, he captured human emotion in the palm of his hand. Watts made it so believable to the point where the action would spill outside of the arena and there was no camera crew present, unless they were shooting interviews, or had another legitimate reason for them to be there.

Even though some fans had doubts, it was so entertaining, that they simply didn’t want to believe that it wasn’t real.

“In our era, people really believed that these two guys hated each other,” Watts recently told SLAM! Wrestling. “We simply protected their belief.”

Watts is often credited for the current, episodic style of pro wrestling. He would create interesting storylines on a weekly basis, attempting to reach out to the local fan base and perhaps even attract fans from other sports such as boxing, who were intrigued by the elements of realism in pro wrestling.

“Promoters need to understand what the demographic wants and give it to them,” Watts explained.

Watts also had a talent roster big enough to draw big crowds wherever they went. There may have been more stars in Mid South than in the sky. It was to the point where the third match on almost every card was main event quality.

“We made a name for ourselves by stacking cards,” Watts said. “So there were about two or three main events on every card and it was successful.”

Much like most things in life, professional wrestling eventually has to evolve. It needs to appeal to new generations, who may want something different than the previous generation. The promoter is the one who ultimately decides which direction to go in and markets to that particular audience.

Watts gave wrestling some credibility with his realistic angles and feuds, but as the ’80s flew by, more and more fans started to realize that maybe pro wrestling wasn’t as real as they thought it was.

Watts was still doing huge numbers as he drew in a sizable percentage of the viewing audience. Despite all of this, the executives at the CBS affiliate network that Watts broadcast on were threatening to throw him off the air, because they saw his program as a show-long advertisement, since he would continuously promote weekly shows on the network. Watts was left with no choice but to sell.

“I was the only guy to sell my business when it was time to get out,” he said. “Everybody else that didn’t went broke.”

Watts sold the company to Jim Crockett Promotions, which ran the original NWA-affiliated Mid-Atlantic territory; in turn, JCP was bought out by Ted Turner’s Turner Broadcasting System in 1988. Watts was later hired as vice-president of Turner Entertainment in 1992 and put in charge of World Championship Wrestling.

WCW was a whole new environment to Watts and he saw the business changing before his very eyes, as it was appealing to an entirely different audience.

“The goal of WCW was to present the product as a movie,” Watts said simply.

In his book The Cowboy and the Cross, Watts compares WCW with the movie Titanic, asking why anyone would want to see that movie, when they already know the ending.

Many of Watts’ ideas came under a lot of criticism, because some people argued that he still had the mindset to make everything believable.

He was eventually replaced as vice-president by Ole Anderson, who was then succeeded by Eric Bischoff.

A recent photo of Bill Watts.

Watts spent a brief period booking for the WWE (WWF at the time), but felt that it was time to make an exit.

While Bill Watts’ tenure had come to an end in pro wrestling, another promoter was about to make a huge splash in the industry.

In 1994, the mood was about to change and Paul Heyman wanted to take the business in a whole new direction. He cranked the volume higher than it had ever been, with three simple letters: E-C-W!

While most wrestling promotions were still family-friendly, ECW, which was originally launched by Tod Gordon in 1992, was targeted at a much more mature audience. It was highly designed for the 18-34 male demographic.

“The original ECW was not marketed at kids,” Heyman told SLAM! Wrestling. “Kids may have been turned on to the action, but I don’t believe they would have been compelled by the storylines.”

Raven

Heyman used the feud between Raven and the Sandman as an example. He says that kids would not have understood or appreciated the emotion of the storyline. According to Heyman, Sandman’s ex-wife being involved with Raven is mature enough, but to add the element of his eight-year-old son worshipping Raven is far too much for young children to understand.

Heyman created a lot of interesting characters during ECW’s eight-year run. Those characters were usually extensions of the wrestler’s actual personality. If not, the wrestlers would play characters that they were comfortable portraying. Heyman always encouraged his talent to take an interest in their characters, so that the audience can believe that was who they truly were and they could get more emotionally involved.

“Most wrestlers get over by playing themselves with the volume turned up, as the old saying goes,” Heyman said. “You have to find people who are willing to step into the skin of a character and adopt that particular persona as an extension of their own.”

Heyman is certainly no stranger to adversity. But he never drinks from a half empty glass. It’s always half full. When he lost some of his talent to WCW, he was able to bounce back by bringing in new talent. Heyman always wanted to keep his target audience happy, but he found creative ways to do that. Instead of bringing in similar talent, he took a different approach altogether.

Paul Heyman and Bruce Hart. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

“When characters leave your company, you have to create new characters or introduce new styles of the genre,” Heyman said. “When [Chris] Benoit, [Eddie] Guerrero and Malenko left, I didn’t want to stay with the Japanese style of wrestling, because it had already been done. So I decided to go for the Lucha style and brought in Rey Mysterio, Psicosis, Juventud Guerrera and those who could adapt the Lucha style to the American audience.”

In a business that’s constantly changing, a good promoter will always try to keep his/her product current. Heyman was a master of that.

“We were always trying new things,” he said. “Bringing in someone new is easier than bringing in an established star, because people had never seen him anywhere else, so they don’t know how to react to this person. They won’t know how to react to the first time he tastes defeat or the first time that someone calls his mother a whore.”

One of Heyman’s greatest creations was Taz, who was the face of ECW in its early days. Heyman had to give his audience what they wanted, while also keeping up with the times. The UFC hadn’t even reached its pre-teen years at the time and Taz was a UFC-based shoot character that nobody knew about. The gimmick was more mature than anything else at the time and had never been done before that point.

Taz

Pro wrestling writer Bill Apter is in complete agreement with Heyman that change is inevitable in pro wrestling. He says it should all depend on what the particular target audience wants and it is up to the promoter to give it to them. But Apter added that sometimes competing companies may have different target markets.

“Wrestling/Entertainment companies are in business to make money,” Apter said. “The WWE caters to many different audience tastes and they can as they have the luxury of so much TV time around the world every day! TNA started out to target the ‘traditional wrestling fan’ audience but there is not enough of that these days for them to stay strictly to a mission like that. You can see now that their shows, like WWE, are targeting a bit of each audience they feel will be compelled to keep buying what they are selling.”

Apter currently works internationally as a columnist for both the United Kingdom’s Fighting Spirit magazine and Italy’s Tutto Wrestling magazine. He is also the Editorial Director of 1wrestling.com and while he appears to be on the outside looking in, Apter has certainly been around the business long enough to give his two cents. He argues that when the demographic changes, the company’s direction must also change.

“The fan is the life-blood of the business. If they don’t buy tickets or pay-per-views you have no business,” Apter said. “How do you draw the new fans in? Brand your business and make it compelling. Make someone who is channel surfing want to stop clicking when your show comes on.”

Bill Apter, still a fan, taking photos in April 2008. Photo by Christine Coons

After ECW folded in 2001, due to financial issues, Heyman was hired as a colour commentator and as a writer/producer for the WWE. A year and a half later, he was assigned to the booking role on Smackdown.

It was a new environment for him, but Heyman accepted the role, even if it meant that he was unable to make the final decisions. The business had to move forward and focus its attention on a new audience, who wanted to see great technical wrestling, so Heyman gave it to them. He was in no way trying to recreate what he had accomplished in the original ECW, because he says what’s passed has passed and he was aiming to please a new generation.

“If you spend your life trying to duplicate what you’ve done in the past, you lose focus and are unable to concentrate on the present,” Heyman said.

With every change that happens, Heyman says two things should always stay the same, regardless of who the target audience is.

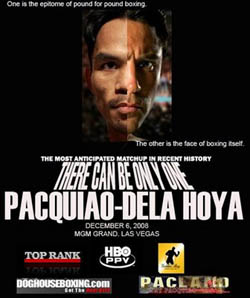

“Before a big match, every promoter should ask themselves, ‘Why are these two guys fighting?’ and, ‘Why should anybody pay to see it?’” Heyman said. “[The recent boxing match] De La Hoya versus Pacquiao was much more intriguing than Calzaghe versus Jones, because it’s a clash of cultures, which is a natural built-in storyline. Calzaghe versus Jones didn’t really click with people, because no one ever explained the significance of the bout. But with De La Hoya versus Pacquiao, it was also the huge personalities fighting it out and the audience understood why this was a must-see attraction.”

Heyman writes a series of columns for his multimedia project The Heyman Hustle, which has a section in the Sun, a UK-based newspaper and website. In his blog entitled “Out with the old, in with the new,” Heyman explains the importance of character presentation.

He says that all promoters should clearly define their stars and give fans a reason to come to their events, because if the fans don’t care about the performers in a match, they won’t care about the match itself.

“WWE programming is light years ahead of anyone else in terms of production value, but the utilization of those production assets is tied up in pyrotechnics and the slick presentation instead of character building mechanisms, which the company has gotten away from,” Heyman described in his column. “Defining the characters, presenting the persona in a manner the audience would understand and giving the public a reason to be interested in the storylines, emotionally involved in the characters and enticed to pay money to see the outcome of a match that was hyped by the arc of the storyline itself.”

Heyman also states in the blog that pro wrestling companies should always reach out to pop culture and create a product that the current fan-base can relate to.

WWE era Heyman.

“Either take the show and re-design the pacing, the formatting, even the way the main events are announced and promoted or change the atmosphere of it to accommodate the pop culture-desirous fan-base that is flocking away from pro wrestling,” he wrote. “It’s time for the writing and production staffs that advise Vince to re-acquaint themselves with what popular movements are taking place, before WWE further victimizes itself by appearing to be out of touch.”

The business has seemingly come around full circle. It appears that the WWE is targeting children again.

“The direction that they’re going in all depends on who their target market is,” Heyman said. “It’s a much more family-oriented product now.”

Apter agrees with that statement, but doesn’t believe that the business has entirely steered away from their previous demographic.

“They (WWE) have not cut out the adult audience. They have just softened the adult product so parents will let their kids watch the shows — and advertisers may consider it a more advertising-friendly environment.”

RELATED LINKS