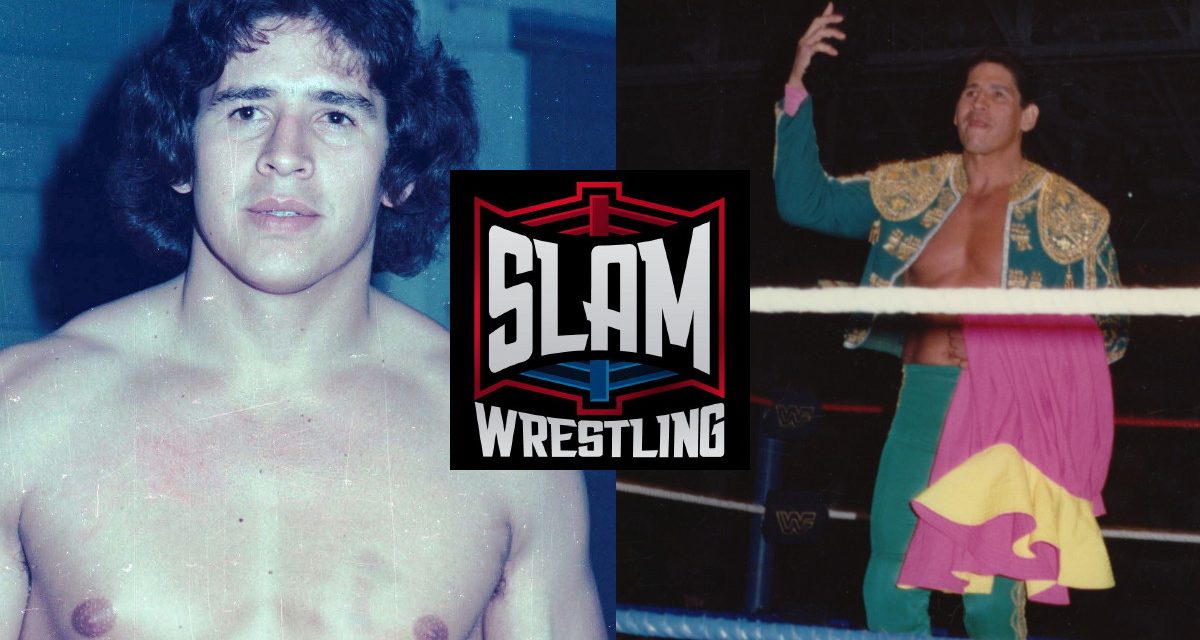

While the names Eddie Guerrero and Rey Mysterio, Jr. immediately spring to mind as Hispanic stars of the latter-day North American wrestling scene, there’s no question that in the prior generation, Mexican hopes were largely pinned on the man billed from the non-existent “Tocula,” Mexico: Tito Santana.

For those who became fans sometime after Mil Mascaras’ appearances at Madison Square Garden — where he was the first wrestler ever to don a mask — Santana was a shining light as a WWF Tag Team champion (with Ivan Putski and later Rick Martel) and multi-time Intercontinental title-holder.

On the back of the release of his career memoirs Tito Santana’s Tales from the Ring, written with Tom Caiazzo, and published by Sports Publishing LLC, SLAM! Wrestling had the opportunity to delve deeper into the story of Tito Santana (real name Merced Solis), chatting to the man himself. Humble, gracious, and thankful of the continued support, Santana took us deep into his career, concentrating on the largely-unknown details of his career outside of the World Wrestling Federation.

“When I was at West Texas State University with Tully Blanchard, I was told that his father Joe wanted to talk to me about being a professional wrestler,” said Santana of his very beginnings in the business. “I hadn’t been a wrestling fan at all. I was always tired, because I played football, basketball, and track, and it was always too late for me when wrestling would come to town around midnight.

“But anyway, I told him that my first love was football. And he replied, ‘Well, you have a chance to make $80,000 a year as a professional wrestler.’ After that, I started thinking that football was such a hard sport, with no security, and with $80,000 in one hand and $20,000 in the other, it was a no-brainer. I started watching wrestling, too, and noticed how a wrestler’s career seemed to be a lot longer than a footballer’s, and I thought that I should go into wrestling.

“So I said that I would give myself four years, and if I couldn’t make any money, I’d get out of the business. It took me four years to get an education, and I was grateful to get a degree out of that, so I’d allow myself that same time to learn the wrestling business. Luckily, within four years I was doing really well.”

Training under Hiro Matsuda may not have been as tough for Santana as it was for Hulk Hogan, but seemingly, getting ring-time was. Despite illusions of $80,000, there was no money to be made for a wrestler who wasn’t being booked. After a few months, not willing to sacrifice the money he had saved from playing football for the Kansas City Chiefs and the British Columbia Lions, Santana was close to walking away from the business. That was, until an old friend intervened.

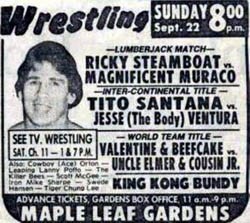

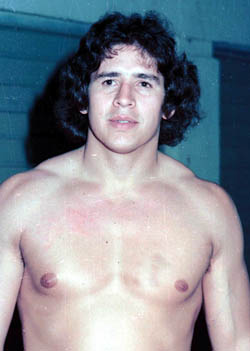

Santana as a feature attraction for a Maple Leaf Gardens WWF show.

“Really, I owe Terry Funk my whole career,” Santana noted. “I knew Terry a little from West Texas State, and one night at the matches he called me into the heel dressing room, and asked me how I liked the business. I said I loved it, but I didn’t know how long I could stay in it, because I’d made some money from football and didn’t want to spend it on renting apartments. He said, ‘Don’t do anything, I’ll talk to Eddie Graham.’ And sure enough, just like that, a couple of days later I had my first match in the Florida territory.”

Though he wrestled more bouts than he did under Joe Blanchard, Santana wasn’t much longer for the Florida territory than he had been for San Antonio. His next port of call was Georgia for Jim Barnett, though the experience was far from the pleasant one that he’d hoped.

“I was very appreciative of the opportunity Jim Barnett gave me in Georgia,” he said. “But I had terrible problems with Ole Anderson, who was the booker, and Dick Murdoch. Both made it very clear that they didn’t like blacks or Mexicans. Ole, in a position of power, had no problem calling me a ‘fucking Mexican.’

“But he was my boss, so I had to take it if I was going to get anywhere. Of course, it hurt very much, but you’re trying to get somewhere, you aren’t going to let a guy like that keep you from accomplishing your goals. These days, I believe you reap what you sew, and Ole has had some bad luck with his health. Perhaps he is reaping what he has sewn.”

Under these circumstances — not to mention that Santana again wasn’t making the money that he had hoped — the then 28-year-old moved on once again, and got his first taste of the big stage, when he began working for Vince McMahon, Sr., and the World Wide Wrestling Federation. Santana spent an enjoyable year in the promotion, which included a six-month WWWF Tag Team Title reign with Ivan Putski. Placed in that position of trust, Santana was willing to respond in kind, so that when McMahon suggested he gain experience elsewhere before returning for a bigger push, Santana was agreeable.

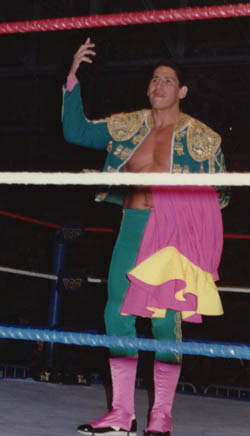

Anybody remember Tito as El Matador? Photo by Terry Dart.

“It was probably the best thing that could have happened to me, because the time that I then had in the AWA was really the most valuable of my career. Mad Dog Vachon told me that interviews were 90% of the job, and that if you were in the business, you had to know how to talk. Vachon, Crusher, Von Rashcke… all the top guys were great interviews, and you don’t learn that overnight. I used to make sure to go to listen to the interviews being done for television, to pick up pointers. It’s good to practice and to lose the fear of the camera, but until you’re involved in an angle, with something real, you don’t know if your work has paid off.”

Santana’s time in the AWA, run by Verne Gagne , may have been valuable for his career as a whole, but his experience was greatly soured when, after a solid two years, he was let go at a vulnerable time in his personal life. Thankfully for him, he was able to find work quickly, back in the rechristened World Wrestling Federation, after another disastrous stint in Georgia with Ole Anderson.

“I ended up being released from the AWA at a time when my wife was six or seven months pregnant, and that’s something that I never forgave Verne for. It made things very difficult for me and my family. So because of that, we had to move for me to find work, which Jim Barnett offered me back in Georgia. But Ole Anderson was still booking, and made it clear he didn’t want me there. Luckily, Vince McMahon was willing to use me again in the WWF.”

While back in New York, for the most famous stint of his career, Santana enjoyed a further World Tag Team Title win (with Rick Martel as Strike Force), as well as an Intercontinental title victory, during which he had Greg Valentine as a frequent opponent. But those title wins would have paled in comparison to having the WWF Title around his waist, which, according to Santana, was strongly considered for him in 1992, in the wake of the WWF steroid scandal.

“It’s true that the company had thought of me as world champion. One day, Pat Patterson came to me and told me that the booking meetings had made a choice between myself and Bret Hart, to become the next World champion. But he immediately said that they’d decided to go with Bret.

“I think they were planning to make a big push into South America, and after The Undertaker and I sold out a basketball arena in Barcelona (in Spain), I think they thought that they could get the same reactions if they did that in South America, too.

“If Vince had decided to go full blast with South America, he would have put the title on me. But I think it was very difficult to deal with promoters in Mexico at the time, as everyone had their hand out looking for something. It was also difficult for Vince to get his equipment across the border, and things like that, and I think that the hassle of it all changed his mind. Then, I became dispensable.”

Moving further and further down the card, then, Santana realized that his tenure in the company was coming to an end. Instead of continuing to languish, however, he offered up his notice, and began to take independent bookings, a bold move considering the relative security of the WWF.

Tito Santana during his brief stay in Florida Championship Wrestling. Photo courtesy Pete Lederberg.

“It was very hard to walk away from the WWF, as I knew there was so much that I still could have done for them. But when they don’t want to use you for whatever reason they have, and they aren’t really being honest with you… I just couldn’t take it anymore.

“I gave my notice without even telling my wife. I knew it was over. I was miserable on the road, and it was such a sacrifice that it wasn’t worthwhile for what I was making. So I said a prayer and asked to leave.”

After short but successful stints with Eastern (later Extreme) Championship Wrestling and the doomed American Wrestling Federation promotion, Santana began to wind down his wrestling career, although he did return to television in January 2000, defeating Shane Douglas on an episode of WCW Monday Nitro. The fact that he didn’t yearn for full-time wrestling was a testament to the difficulties a family man faces on the road.

“Once I left that road schedule, there was no temptation at all to go back. I love my home, I love my family, so I didn’t miss that part of the job one bit! These days, people ask me if I’d like to work behind the scenes in the WWE, but I know that if I did, I would have to be on the road constantly, and I don’t want to do that. Being on the road at least four days a week isn’t for me right now.”

In what was a fitting tribute to his career, in 2004 Santana was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame, along with contemporaries such as Bobby “The Brain” Heenan, Superstar Billy Graham, and Harley Race. Typically, Tito spent his last moments with SLAM! Wrestling speaking highly of these men, and the many other characters that made wrestling the spectacle that it was.

“When I think about the old days, there was always a definite good and bad guy, and everyone had their own characters,” he concluded. “George Steele, Lou Albano, Hulk Hogan — these were all great characters.

“Nowadays, everyone comes out to the ring all greased up, with muscles all over the place, looking the same. Everyone is just a bodybuilder. You can be a babyface one night, and a heel the next.

“Our business is an art, but there aren’t so many great artists around anymore. For young wrestlers, there aren’t a lot of places to get experience. This great business has changed, and it will never be the same.”

RELATED LINK