In the golden era of professional wrestling, Northern Ontario was a hotbed for aspiring young French-Canadian wrestlers.

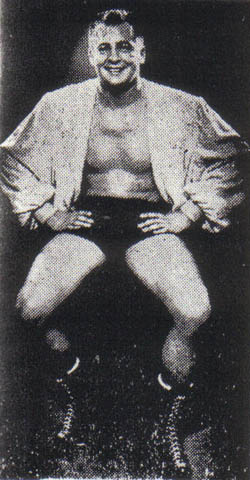

Frenchy Roberre.

Many up and comers of the day, including Louis Papineau, Johnny and Jacques Rougeau, Frenchy Roy, Tony Baillargeon and Maurice and Paul Vachon plied their wares in Larry Kasaboski’s far-flung Northland Wrestling territory in the mid-1950s.

Not to be forgotten among this august group of grunt and groaners was a young fan favourite named Frenchy Roberre, often billed as being from Montreal and sometimes referred to as Maurice Roberre.

Word has reached the wrestling world that Roberre passed away on July 13 in Portland, Oregon. Details of his death are still sketchy but it is being reported that he died in a nursing home.

One of the daunting tasks of wrestling historians and reporters on such occasions is to piece together the careers of wrestlers such as Frenchy Roberre when little details are known. It is often difficult to separate fiction from fact.

Yvon Losier was born on September 10, 1930, in New Brunswick to Lina (Robichaud) and Willie P. Losier. He left his hometown at the age of 16, ending up in Niagara Falls, ON, where he learned the masonry trade.

His wrestling career began in the early 1950s, and throughout his career, Frenchy was known as “the Montreal fireball” and an exponent of scientific wrestling. He was sometimes introduced as being from New Brunswick or Nova Scotia. It was even rumored that he was a protégé of the iconic Whipper Billy Watson and that the Whip had taught him the whipcrack, a hold that Watson made famous.

I first saw Roberre in Pembroke, Ontario in 1956 when he was starring on the Kasaboski circuit. He was known as Maurice “Frenchy” Roberre at that time but would later become Yvon Roberre on the Gulf Coast to avoid confusion with another Quebec wrestler working in the Chicago area who called himself Maurice Roberre. The two were not related. Frenchy’s real name was Yvon Losier while Maurice Roberre was born Maurice Boissy.

There was no connection between either of the Roberres or the legendary Yvon Robert who was one of the all-time great Canadian matmen, other than the similarity in their surnames and the fact that they were all from Quebec.

Tall, lean, handsome and sporting a trademark brush cut, Roberre was the poster boy for clean-cut wrestling heroes of that period. He dished out a pleasing brand of wrestling to Northern fans regardless of his place on the card.

He gave as much effort in a preliminary match against Haru Sasaki as he would while teaming with Jack Laskin against the likes of villainous duos such as Don “One-Man-Gang” Evans and Wild Bill Savage in main events.

“He was an acrobatic type of wrestler,” recalled North Bay wrestling legend Bill Curry, “very popular with the ladies and very easy to handle. He was in his early twenties when he came to us but had been wrestling for a few years in Montreal.”

Curry also did some booking for the Kasaboski promotion and remembers Roberre as a dependable worker who always showed up and gave a solid performance.

“He was a credit to the game,” Bill concluded.

Like many promising young grapplers of that era, Roberre picked up some much needed experience in Northlands before moving on to greener pastures. He hit his peak on the Gulf Coast where he reigned as heavyweight champion in 1958 and 1960 as Yvon Roberre, working among elite company such as Mario Galento and Billy Wicks. As wherever he appeared, Frenchy was quite popular with fans in that area and had major feuds with The Great Malenko and Pancho Villa.

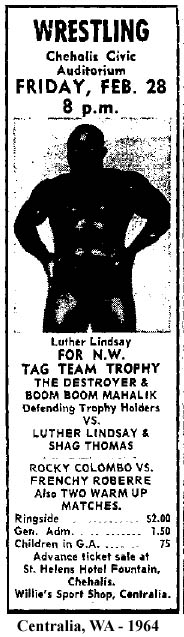

When he departed the Gulf Coast he headed for the Pacific Northwest and spent many years in Portland where he homesteaded and eventually became part owner in a tavern. He also toured British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon extensively.

Former Pacific Northwest promoter and current executive director of the Cauliflower Alley Club, Dean Silverstone, recalled the occasion in 1962 when Roberre appeared on a card in Seattle

The main event on the card featured Gorgeous George matched against Leo Garibaldi in a “floating ring.” Even though he had appeared in the opener, Roberre came back with fellow wrestler Al Fridell to referee the special match.

The pair rowed around the ring in row boats acting as water referees in case either the Gorgeous One or Garibaldi took a dive into Green Lake. Silverstone remembers that after Frenchy’s retirement, the popular wrestler purchased a small motor home and continued exploring the Pacific Northwest. It would have been a welcome change for him to finally tour the area in the daylight hours after many years spent on the road at night.

But perhaps his spirit of adventure extended beyond the northwest. Al Campbell, a long time wrestling observer from Sudbury, Ontario last saw Roberre about 10 years ago, passing through the Nickel City in a motor home. Campbell had met Roberre at several wrestling gatherings in the past.

In 1997, Yvon “Frenchy” Roberre was inducted into the Northwest Wrestling Hall of Fame during a ceremony held in Issaquah, Washington, at Silverstone’s home, with over 100 professional wrestlers in attendance.

He was typical of many wrestlers from the era in which he excelled — ambitious, hard working, eager to learn, leading a nomadic lifestyle and loyal to his fans.

He was not a major star as some have pointed out but nonetheless a shining star that helped light up the wrestling galaxy in a golden age.

Losier is survived by his daughter, Annette Schulz; siblings, Emilie White, Jocelyne Losier, Yvette LaFlamme, Lucienne Losier and Jean Marc Losier; grandchildren, Samantha Monroe and William Young.