His given name was George Dahmer, his family called him Hootie, but to a generation of pro wrestling fans around the Great Lakes, he was Chief White Owl, one of the top grappling Indians of his time.

Whether it was bopping an opponent’s skull with his signature tomahawk chop, amusing colleagues with a war dance set to a pop tune, or advancing the careers of other wrestlers, cohorts recalled White Owl as good with fans and good for the business.

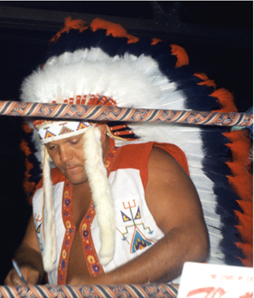

Chief White Owl. Photos by Steven Johnson

“I have lots of fond memories of him,” said Johnny Powers, who worked on and off with him for more than a decade. “He was a good dancer and he used to do a dance to ‘Mustang Sally.’ He would break out with the Indian war dance to ‘Mustang Sally;’ isn’t that a dichotomy? But it worked.”

White Owl died May 23, 2008, at the JFK Medical Center in Atlantis, Fla., not far from his home in Boynton Beach, where he had lived since 1984. His passing dissolved another bond to the days when pro wrestling was chockfull of cowboys and Indians, with the differences between good guys and bad guys carefully delineated in fans’ minds.

“You know how promoters would ask the fans to write in, ‘Who’s your favorite?’ ” asked Bobby Fulton of the Fantastics, who followed the Chief as a youngster in Ohio and was in contact recently with his family. “He was the one that the people chose back in Ohio as their favorite. Some territories didn’t want people to get over, but they just happened to get over when the office wasn’t pushing you. The fans took to him.”

Born June 19, 1935 in Wilmington, Ohio, White Owl grew up in a family of about 10 brothers and sisters — one brother, William, wrestled briefly as a part-timer named Pancho Villa. The Chief started out on small shows in southern Ohio as a teenager and first came to note as a pro under his real name around 1956. Later that year, he took on the role of White Owl at Columbus promoter Al Haft’s suggestion and officially became a wrestling Indian.

According to Patricia, his wife of 49 years, the gimmick had a basis in fact. White Owl’s mother was of Indian descent, though she passed away when the Chief was five. He was billed as part of the Cherokee Indian Reservation in North Carolina, and his wife said that’s where “Hootie” got some of his colorful feathers.

He was a regular on Haft’s circuit in the late 1950s, working as a singles and tag wrestler with partners like Leon Graham and “brother” Yaqui Joe until the promotion fell on hard times in 1963-64. Perhaps the highlight of his time in the territory came in July 1959, when he won the Golden Trophy in Charleston, W. Va., after Jan Madrid accidentally knocked out Al Galento, White Owl’s adversary. And, according to news accounts, White Owl’s skill at venting his spleen nearly sparked an April 1959 riot in Weirton, W. Va., when he came to Yaqui Joe’s aid in a match against Buddy Rogers.

The stocky Chief, who went about 5-10 and 230 pounds, started to spread out his mat activity by the early 1960s. He headlined against Rogers in Montreal in 1960, worked in Colorado, Florida and the Bahamas around that time and became a major player in two angles in Pittsburgh in 1964 that set up top-level feuds for other workers.

In one, he was badly bloodied during a TV match against Powers, who was climbing the ladder for a shot at WWWF champ Bruno Sammartino. “He actually helped me get over in Pittsburgh, which was my first break,” Powers said. “He was a bleeder and I did an impromptu Jackie Gleason slide on his blood on the linoleum of the studio and then I thought maybe I just better top it off and put a little exclamation on it, so I turned to the camera and rolled my eyes and I got kicked off TV for it.

“As a human being around the fans and us guys, he was easy-going and he never bitched about paydays. He took what the going rate was and played his position well,” Powers reflected.

Cowboy Bill Watts also indirectly credited White Owl for a push he got in the Steel City territory. “Chief White Owl was there and he was getting over pretty well as an in-between babyface on TV,” Watts recalled in his autobiography, The Cowboy and the Cross.

In a televised match against Frank Martinez, White Owl legitimately broke his leg and Watts, thinking quickly, rushed from backstage to challenge anyone who would dare to hurt his friend. “White Owl went to the hospital and became a star with the sympathy, and I was over like a million bucks in Pittsburgh.” Indeed, for one spot show, Fred Hevia, a Pittsburgh area sportswriter, called White Owl “probably the most popular wrestler in the Mon Valley district.”

The cheers were real, but the off-stage story was painful, Patricia Dahmer said. He was in a cast from foot to hip and she couldn’t wiggle him into a car for the long ride back to the Columbus area. “I turned him upside down and everything,” she said. Promoters arranged for a plane trip and, as their transportation woes continued, the Dahmers missed one flight and finally caught another, only to fly through heavy turbulence. “We were miserable. I kept thinking we were going to crash,” she said.

Still, he recovered from the injury to form prominent tag teams in the WWWF with Wahoo McDaniel and Chief Big Heart. One of his career highlights was teaming with Big Heart to stop Waldo von Erich and Smasher Sloan in Madison Square Garden in May 1965.

Out of gimmick.

White Owl was a jail guard and deputy sheriff in Washington County, Ohio, during his career, but usually wrestled several night a week, his wife said. The late 1960s saw him as a fixture in Ed “The Sheik” Farhat’s Detroit-based promotion, which is where the future Big Jim Lancaster witnessed him as a fan.

“I first encountered Chief White Owl as a front row kayfabe mark back in 1967 in Dayton, Ohio. The first main event I watched him win was an Indian Strap Match over Dr. Jerry Graham,” Lancaster said. “He always got solid TV wins, but was always the babyface they pinned to launch a new heel into the next main event.”

He got regular matches with The Sheik and Bull Curry, which meant rivers of blood flowed through the ring in places like Mansfield, Ohio, for little more than chump change; Farhat’s payoffs were notorious for barely supplementing day labor. To Ron Martinez, son of Buffalo, N.Y., promoter Pedro Martinez, that’s why White Owl was eager to jump to the National Wrestling Federation when it cranked up operations around 1970.

“He was a disgruntled member of The Sheik’s crew at the time, when Dad proposed that he come to work for us in Cleveland and Akron, Ohio,” said Martinez, a TV announcer and key figure in the NWF. “He was making $25 a shot working for Mr. Farhat and was not happy. Dad guaranteed him $75, a fortune at the time. This was 1972, don’t forget. He was a mid-card performer for us, very popular with the fans.”

Chief White Owl, Cincinnati promoter Les Ruffin, Toledo promoter Martino Angelo, and Dan Miller in 1967 in Detroit. Photo by Dave Drason Burzynski

White Owl held the NWF tag team title with Luis Martinez and had running feuds with Don and Johnny Fargo, Von Erich, Hans Schmidt, and others. Perhaps his most amusing time in the NWF came in July 1971, when he confused the names of a pair of upstate New York towns with Indian names, and headed to a show in Oneida instead of Oneonta. Catching his error, he rushed to back to beat Mr. X in front of 2,000 fans.

“He mounted his trusty steed and arrived in time to win a match while the excited fans chanted ‘go, Chief, go,’ ‘go, Chief, go’ in perfect — although unrehearsed — unison,” Oneonta sportswriter Bob Whittemore quipped.

In the ring, White Owl was easy to work with, though his tomahawk chops carried a sharp sting of realism. Lancaster was scheduled to work with the Chief on Cleveland TV during the NWF run, and said Dick “Bulldog” Brower warned him beforehand not to clench his teeth as White Owl prepared to launch a chop to the cranium.

“Man, was he right!” Lancaster said. “Owl was stiff, but he didn’t do it too prove how tough he was or to teach the new guy a lesson. He seemed to get carried away with the crowd and just popped you hard. All I got in was the obligatory TV-jobber heel, punch-kick-punch-eye rake, babyface comeback … lose.”

Bruce Swayze worked with White Owl dozens of times in the NWF and also attested to his popularity. “His chops were a little stiff. His gimmick was the dance. He didn’t do a lot. He did that war dance and the chops. That’s basically what he did, but that’s all he needed. I was fond of him, never had a problem. We always had a few laughs and my heart goes out to his family,” Swayze said.

After the NWF folded, Powers brought White Owl into the Carolinas-based International Wrestling Association in 1975. The Chief also wrestled back in Ohio for Fred Curry and entered the ring for the final time in 1983 as part of an event at a high school.

In addition to his wife, White Owl is survived by a son, a daughter, four sisters, and a brother. Services were private.

“What a character,” said Ron Martinez, who fondly recalled how the Chief once helped himself to some extra drinking glasses during a fill-up at a service station promotion. “He was a gentleman. A somewhat bent gentleman, to be sure, but one nonetheless.”

RELATED LINK