Before Gorgeous George was “Gorgeous,” back when Stu Hart was just “Stewart,” Enrique Torres stood atop the mat game.

And though 40 years have passed since he last laced up his boots, there’s little doubt that the star of Torres, who died Sept. 10 at a Calgary nursing home, burned as brightly as any of his peers.

During his more than 20 years in wrestling, he held championships across the United States and Canada en route to becoming one of the most decorated wrestlers of his era.

The Torres Brothers: Enrique, Alberto, Ramon Photo courtesy Wrestling Revue Archives

Born July 25, 1922 in Santa Ana, Calif., near Los Angeles, Torres was the oldest of three wrestling brothers, as Ramon and Alberto followed him into the sport, though he recalled that his parents objected to the profession for all three.

“I had no intentions of ever wrestling professional,” said Torres, who had a long amateur background in California. “I just wrestled amateur because I liked the sport to start with.”

But after watching some local matches, “I figured that I could wrestle, too, professionally,” he said. “My folks, my parents, they did not want me to start wrestling myself, professionally, but I did and then they [Alberto and Ramon] went after that.”

He debuted in 1946, just as television was discovering the sport in California. With his good looks and humble personality, he became an instant hit. “I didn’t change my name or anything,” he said in an interview in 2006. “I didn’t have a gimmick of any kind. I was just Enrique Torres and that was it.”

Always a fan favorite, Torres wrestled at about 230 pounds. Lots of flying body scissors and dropkicks marked the career of the man billed, in a bow to his ethnicity, as the Latin Flash. Not that the press didn’t try to make more out of it. A newspaper in Los Angeles that catered to the Mexican market advertised him as the “Panther from Sonora, Mexico,” he recalled.

While his parents were from Mexico, he was a native California. “It didn’t hurt to advertise that, but I never wore any special thing. I let the wrestling speak for itself. I didn’t talk too much on TV or anything like that. I didn’t holler. I just wrestled. That’s all I did.”

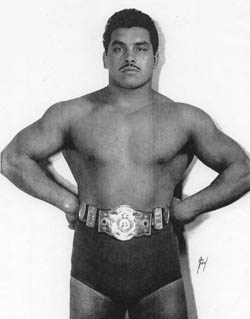

Enrique Torres

In California, he captured a version of the World title from George Becker in 1946, just a few months after his pro debut. He was billed as World champion on the West Coast for about four years, spending his off-hours in Texas. “I was traveling a lot between Los Angeles, Phoenix, Arizona, and El Paso, Texas, places like that,” he said. His appeal reached beyond in areas without a concentration of Latinos — Torres cited St. Louis as a place “where I was always received real good.”

California promoter Hardy Kruskamp couldn’t lavish enough praise on Torres. In a 1948 “Pan Patter” column in his boxing and wrestling program, Kruskamp said Torres was tops in singles wrestling ability. “No one for the last ten years that has entered the game has had so much on the ball. Everything in the books of a great wrestler has been endowed in his young and well conditioned body. His standing of the year previous was in the gold medal class and would have still been today at this writing if he had not taken time off to travel around other sections of the country and try out his wares.”

In 1952, Torres and rival Baron Michele Leone landed in Santa Monica, Calif., Superior Court where two fans maintained they were injured when Leone tossed Torres into the crowd. “If I could forward pass a man like Enrique,” Leone said, “I’d quite wrestling and try for the [Southern Cal] football team.” The two were exonerated in the end.

One of his greatest bouts came in February 1953, when, billed as Pacific Coast champ, he held world champion Lou Thesz to a one-hour draw before a record gate of nearly $5,000 in Sacramento, Calif. “It was a wild finish for the packed house,” the Sacramento Union reported.

Watching his work with envy, Torres’ brothers kept bugging him to let them turn pro, but Enrique laid down some conditions first. “I told both of them to join a wrestling team. They joined a wrestling team in San Francisco, at the YMCA and other places. Join a wrestling team and learn how to wrestle.” After Alberto and Ramon competed as amateurs, Enrique gave them his blessing to join the professional ranks.

In San Francisco, Torres teamed with Bobo Brazil, Leo Nomellini, Ronnie Etchison, and Johnny Barend for tag championship reigns in the 1950s, and was Pacific Coast tag champ with brother Ramon, Etchison, Nomellini and Jess Ortega on and off from 1952 to 1954. He and Alberto also held tag belts in Texas.

Torres was Central States champion in 1952 and again in 1963. During the famous Vachon-Torres brother wars in Georgia, he held the territory’s version of the World tag crown twice with Alberto and three times with Ramon in 1966 and 1967. Alberto died in 1971 after wrestling with a ruptured pancreas. “We didn’t know he was sick,” Enrique said. Ramon died in 2000.

Enrique Torres in 2005. Photo by Shuhei Aoki

He stepped away from wrestling in 1968 after the headlining run in Georgia, looking after his mother and tending to family properties in the Los Angeles area after his father died. “When I began, I didn’t think I would be able to make a living. But I did make a good living out of it.”

After retiring, Torres and his wife Kata lived in California and Nevada before moving to Calgary 20 years ago. In recent years, Torres suffered a stroke, had been on kidney dialysis for several years and had a kidney transplant in 2006. He was a resident at Carewest George Boyack Nursing Home in Calgary when he died. He is survived by Kata, to whom he was married for 44 years, four children, two stepchildren; and a sister. A funeral will be held Friday in Calgary.