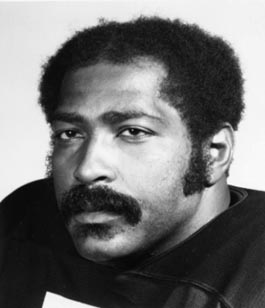

Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time. Just as wrestling in Cleveland was heating up in late 1968, along came Walter Johnson, an All-Pro defensive tackle with the Cleveland Browns, to try his hand in the ring.

Johnny Powers, who booked Cleveland and got Johnson started as a wrestler, saw an opportunity to cash in on a hometown hero with a legitimate athletic background. In fact, in just his second match at the Cleveland Arena, Johnson put wrestling on the front page of the Cleveland Plain Dealer sports section, unheard of at the time.

Walter Johnson. Courtesy The SPORT Collection

The only problem, Powers soon found, was that Johnson’s greatness on the gridiron didn’t translate into wrestling mastery. And therein lays a cautionary tale, especially in light of the attention lavished on “Pacman” Jones’ recent alliance with TNA Wrestling.

Despite a superficial resemblance, the skills and abilities needed to succeed in pro football and pro wrestling are not the same. Someone — or, in Johnson’s case, lots of “someones” — is liable to get hurt. “He was stiff, which is okay, but you’ve still got the get the job done,” Powers reflected. “Football players can be kind of clumsy.”

There was little doubt that Johnson would make it big in pro football. A second-round pick in 1965 out of California State-Los Angeles, the 6-foot-4, 265-pounder became a regular for the Browns in his second season. He was a three-time Pro Bowler, set a team record for consecutive games played, and paired with Jerry Sherk as one of the top NFL tackle tandems of the early 1970s.

Known as “Zoom” for his quick getaway from the line of scrimmage, Johnson reasoned he had what it took to carve out a niche in another profession. “I use some of the same moves in both sports. I tackle people both on the field and in the ring. I also fight on the field to take men down and do the same in the ring,” he explained to The Post-Journal of Jamestown, N.Y.

Wearing his No. 71 jersey to battle, Johnson worked his way up the ladder from the fodder like the Masked Destroyer to Angelo Poffo before moving to main events with Powers against the Love Brothers in the spring of 1969. “We were the hottest thing in Cleveland around then,” Powers said. “He did something to the card.”

Johnson wrestled only occasionally for the next couple of years, but really stepped it up in 1973 as his football career was winding down. He was a fixture on cards in Cleveland and nearby Akron, and worked a lot of spot shows for the Buffalo-based National Wrestling Federation.

“He was an imposing guy. This is sports entertainment, so we don’t want to get carried away, but he was imposing. He was thick,” said Ron Pritchard, a Cincinnati Bengals linebacker and ex-wrestler. “He didn’t do that a lot of years, so it wasn’t like he was overly ring-savvy. But his presence was such, and with the Browns tag, it didn’t matter.”

Johnson’s most memorable rivalry came against Pritchard in an intrastate “Browns versus Bengals” feud that only deepened divisions among Ohio fans who took their football allegiances as slightly less consequential than life and death. In February 1974, their match for The Sheik’s promotion in Cincinnati got the crowd so stoked that other wrestlers raced to the ring to calm matters.

“Sheik went out, as did most of the dressing room,” said Big Jim Lancaster, who was on the card that night. “They were still in the ring and pounding each other so hard you hear them very distinctly clear back to the dressing room.” Pritchard won by disqualification.

“It was natural with me playing for the Bengals and him playing for the Browns,” explained Pritchard, now a school athletic director in Arizona. “When he was in Cleveland, Walter was the good guy. I was the heel. When we came back to Cincinnati, Walter was the heel and I was the good guy. So it worked out nicely.”

Johnson finished his career with the Browns in 1976 and ironically was part of the 1977 Bengals before hanging up his cleats. He wrestled around Indianapolis in 1978 and 1979 for Dick the Bruiser and Wilbur Snyder. There, Lancaster finally got in the ring with him, and he’ll never forget it.

Walter Johnson signs an autograph. Photo by Steve Johnson

“My chest still hurts,” Lancaster said. “He may be the most powerful man I worked with. I mean that seriously. It was lights out right from the start. First time we locked up, he slapped my ear and I thought I would go deaf. I don’t think it was on purpose; it was just being clumsy.”

Johnson seemed disinclined to do any chain wrestling on the canvas, so Lancaster elected to protect his own well-being rather than put on a five-star performance. “I grabbed a headlock, had him shoot me into the ropes. He stood strong while I was to bounce off him. He merely leaned forward and it almost knocked the wind out of me. I thought if this guy can’t find work in football, I didn’t want anything to do with the NFL.”

Johnson won the match with his three-point football tackle. Incredibly, Lancaster said, “it was the lightest thing in the match and still hurt.”

Mike DuPree got a bitter taste of Johnson during a TV taping in Louisville, Kentucky, for Angelo Poffo’s ICW promotion in the late ’70s. He was working as a heel in a tag bout against Johnson and Pez Whatley, and candidly recalled Johnson as “a stiff idiot.”

“Johnson threw me in the ropes. I was about 175 pounds at the time, and my feet never hit the canvas. I sprung off the ropes, a total shoot, and he football-tackled me like a football dummy. I must have been a dummy to be in there, I suppose. If the ropes would have broken, I would have bounced off of the wall of the small studio we were in. He did this three or four times. I smacked his back and ended up knocking my jaw loose,” DuPree said.

Walter Johnson’s 1976 Topps football card.

Just like Lancaster found, the gentlest move Johnson employed was his finisher — in this case, a bearhug. “The only thing he the only thing he seemed to have to me was being big,” DuPree said. Johnson’s shortcomings on the mat knew no international boundaries, either. Powers, one of the biggest North American stars in Japan during the 1970s, once hooked up Johnson with New Japan Pro Wrestling. “New Japan wasn’t happy. They said. ‘JP, don’t be sending us that over here again.'”

Johnson’s last run of consequence was in California, where he was Americas champion in the Los Angeles promotion for three months in 1980. He also held the territorial tag titles with Al Madril and “Bullwhip” Danny Johnson. By his own admission, he preferred to stay close to home. “The money is good,” Johnson, who also owned a car wash in Kentucky, told the Associated Press. “But the one thing I don’t like is traveling. You have to travel to make a lot of money.”

He wrestled for some independent promotions in the early 1980s and ran a few shows in and around Ohio before leaving the business. Farhat left him with a nasty going-away present in 1984, when Johnson unaccountably involved himself in a match between Luis Martinez and The Sheik.

“It’s not a good idea to strong-arm Sheik at the best of times, but Sheik was in pain and not his usual jovial self,” said DuPree, who was wrestling that night and got a chuckle out of The Sheik’s reaction. “He put a backward checkmark into Johnson’s large cranium. It was so deep that it didn’t bleed. Johnson came back to the dressing room pacing back and forth going, ‘Ut, ut,’ and gingerly touching his wound.”

J.B.Psycho ties up Walter Johnson. Photo by Steve Johnson

Johnson went into private business and later headed an alarm security firm in Cleveland. In late 1995, Browns owner Art Modell announced he planned to skip town and move the franchise to Baltimore. Perhaps things would have been different if some promoter could have coaxed Modell into the ring to experience Johnson’s blunt force. “It’s as if someone went into my personal biography and took out 11 years of my life and ripped it right out of my book,” Johnson said to NBC’s Dick Enberg. A few months later, he was dead of a heart attack at 56.

Though Johnson’s wrestling career spanned parts of 15 years, looking back, his contemporaries agree that he had more in common with football players who never grasped the intricacies of the sport, like Kevin Greene or Steve McMichael, than more celebrated two-sport stars like Ernie Ladd or Angelo Mosca.

“He was a good guy. Never gave trouble,” Powers said with a chuckle. “But he couldn’t learn the game.”

RELATED LINKS

- September 8, 2005: The brief career of “Big Daddy” Lipscomb